Who Was in Paris? Musings on the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay

Sculpture dedicated to Gu (around 1858) by Ekplékendo Akati. Louvre Museum. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

Power Figure (Nkisi N’Kondi), Kongo peoples (late 18th – early 19th c.). Louvre Musuem. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

Nok sculpture from Nigeria (6th c. BC-6th c. AD). Louvre Museum. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

BY TA’ZIYAH JARRETT (Research Assistant - Critical Race Museology Cluster)

In “Blackening the Louvre Museum: Beyoncé, Jay-Z, and the Legacies of Slavery”[1], art historian Ana Lucia Areujo argues that Jay-Z and Beyoncé’s music video for their song Apeshit – in which the duo and Black dancers perform in the Louvre’s empty halls and in front of some of its most famous pieces – is an example of Blackness being celebrated in a space in which it is not usually present, namely the Louvre.[2] I had never been to the Louvre before, but I had heard that it was a massive space, so when I came face to face with the famous glass pyramid in July of 2023, I was grateful to have something to orient my visit. I took note of the pieces that Areujo mentions – ones that (however inadvertently) engage with legacies of slavery – and I decided to keep an eye out for additional instances where celebrations of empire and European creativity could have made room for the acknowledgment of the legacies of colonialism and imperialism.

The Great Sphinx of Tanis (c. 2600 BC). Louvre Museum. Photo: Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

With that in mind, I was surprised that the very first thing I saw upon entering the museum was a section devoted to Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americans (the Pavillon des Sessions). Based on my limited knowledge of the Louvre’s collection, and the narrow focus of Areujo’s short piece, I assumed that my exposure to Blackness — in any form — at the Louvre would be extremely limited. To the contrary, in addition to this section, the Louvre has a vast collection of Egyptian artifacts. In hindsight, since many major museums have a section dedicated to Egypt and its artifacts, one could argue that it would be unusual not to see African art on display. However, these same museums often focus on Egypt alone, isolated from the rest of the African continent. I have no doubt that this common distinction is influenced by the centuries-old argument that ancient Egyptians were not Black (some Egyptologists go so far as to say that they were Caucasian).[3] Ultimately, the fact that I had probably internalized this fabricated dichotomy between Egypt and Africa – and had subconsciously thought that Egyptian art did not “count” as African – leaves me with a feeling of resentment

It is important to note that the Louvre has multiple entrances, and the one we used (the Porte des Lions) was a side entrance, and a notably less busy one at that. For that reason, it is likely that my first encounter with the Louvre does not reflect that of most visitors. That is to say, African art is not usually the first thing one sees upon entering the world’s most famous art museum. In fact, unless they were actively looking for it, it seems unlikely that the average visitor would see the Pavillon des Sessions at all, due to the section’s relative isolation from the rest of the galleries

Now, looking back, I can’t help but feel like the museum was trying to appease its audience. In the collection’s welcome panel, the museum admits that it only included non-European art – which it had long considered “primitive” – after a multitude of artists, anthropologists, and art historians pressured them to do so throughout the 20th century. The Louvre is understood as being a – if not the – representative of Western art. This is reflected in its organization, which Carol Duncan describes as “a programmed sequence of collections that maintains the nineteenth-century bias for the great epochs of [Western] Civilization.”[4] As such, insofar as Black people are not conceived as belonging to “the West” (despite most of it being built using their labour), it is no surprise that African artwork was excluded and is now segregated and eclipsed by the rest of the Louvre’s collection.

Arabe d’El Aghouat en burnous (1856) and Femme des colonies (1861). Both by Charles Cordier. The Musée d’Orsay. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

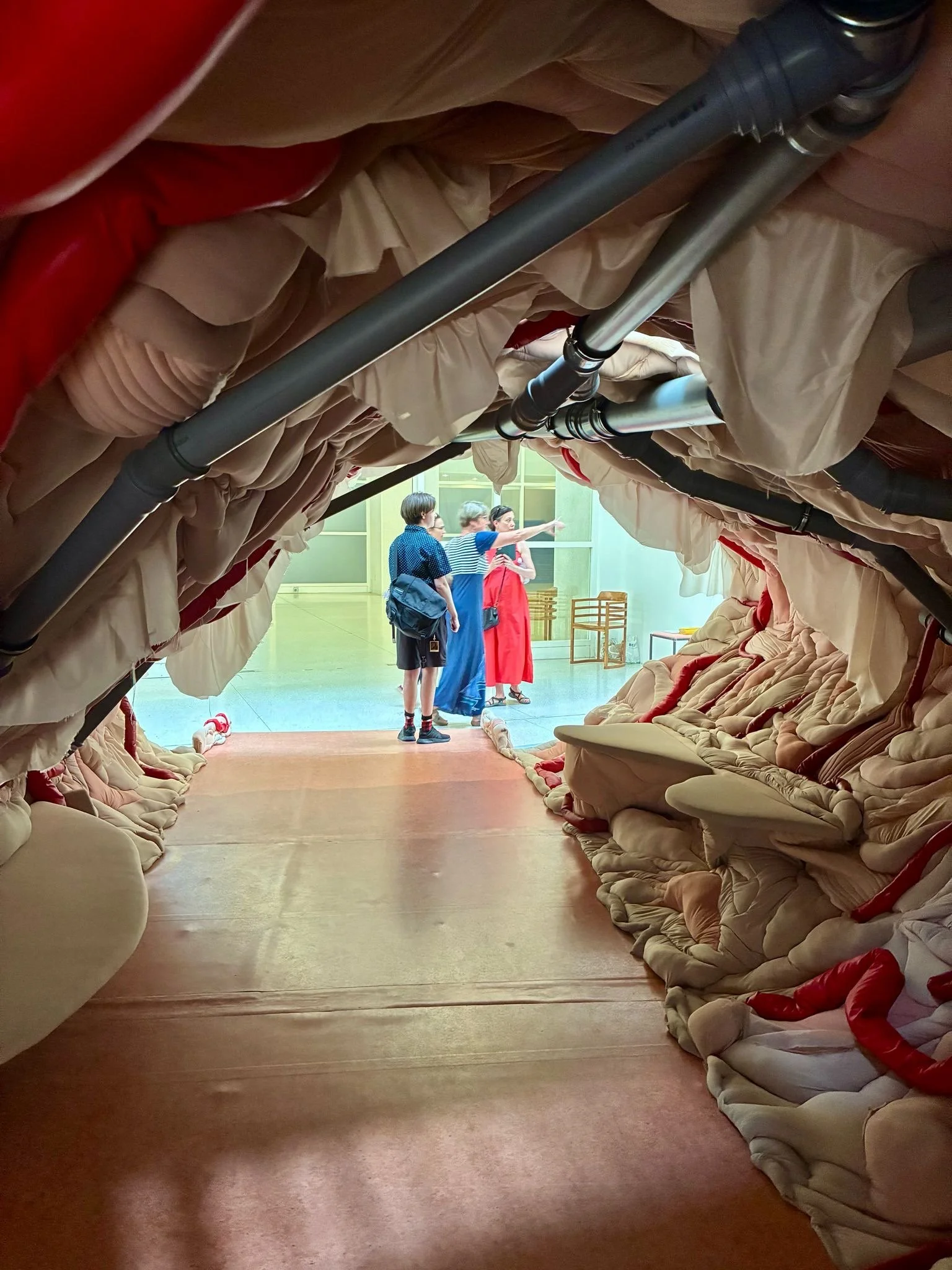

It is interesting to contrast my experience at the Louvre with my experience at the Musée d’Orsay. Notably a former train station, d’Orsay showcases a variety of late 19th century to early 20th century artwork. If my prior knowledge of the Louvre was limited, then my knowledge of d’Orsay was non-existent, so I visited with no expectations, least of all seeing Black artwork. As such, I felt the same sense of surprise (albeit muted) when I saw busts of Black people on the museum’s main floor. Although they were few and far between, unlike in the Louvre, these pieces and others like them were displayed alongside European artwork. Thus, Black bodies were visibly present in otherwise White gallery spaces.

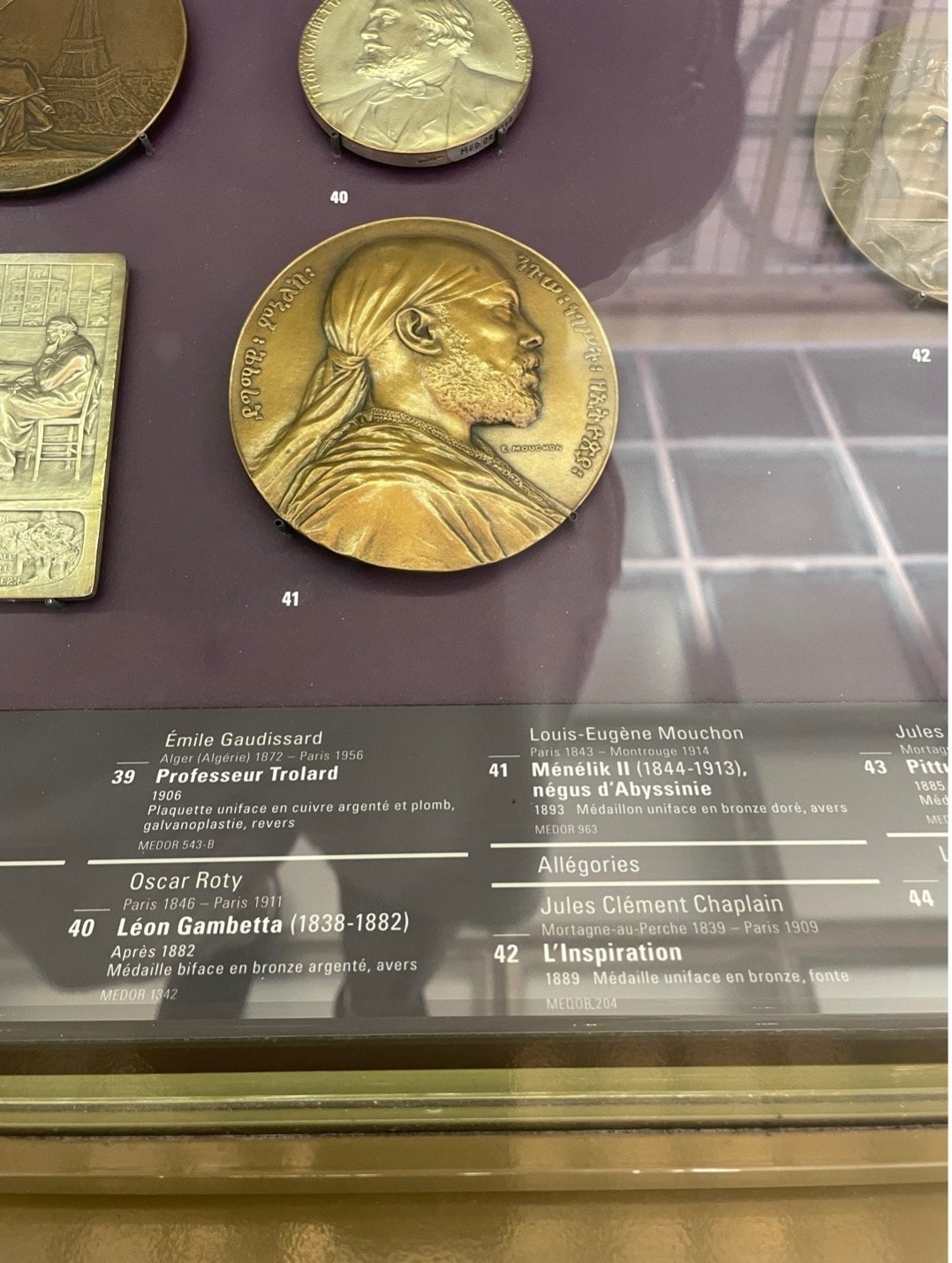

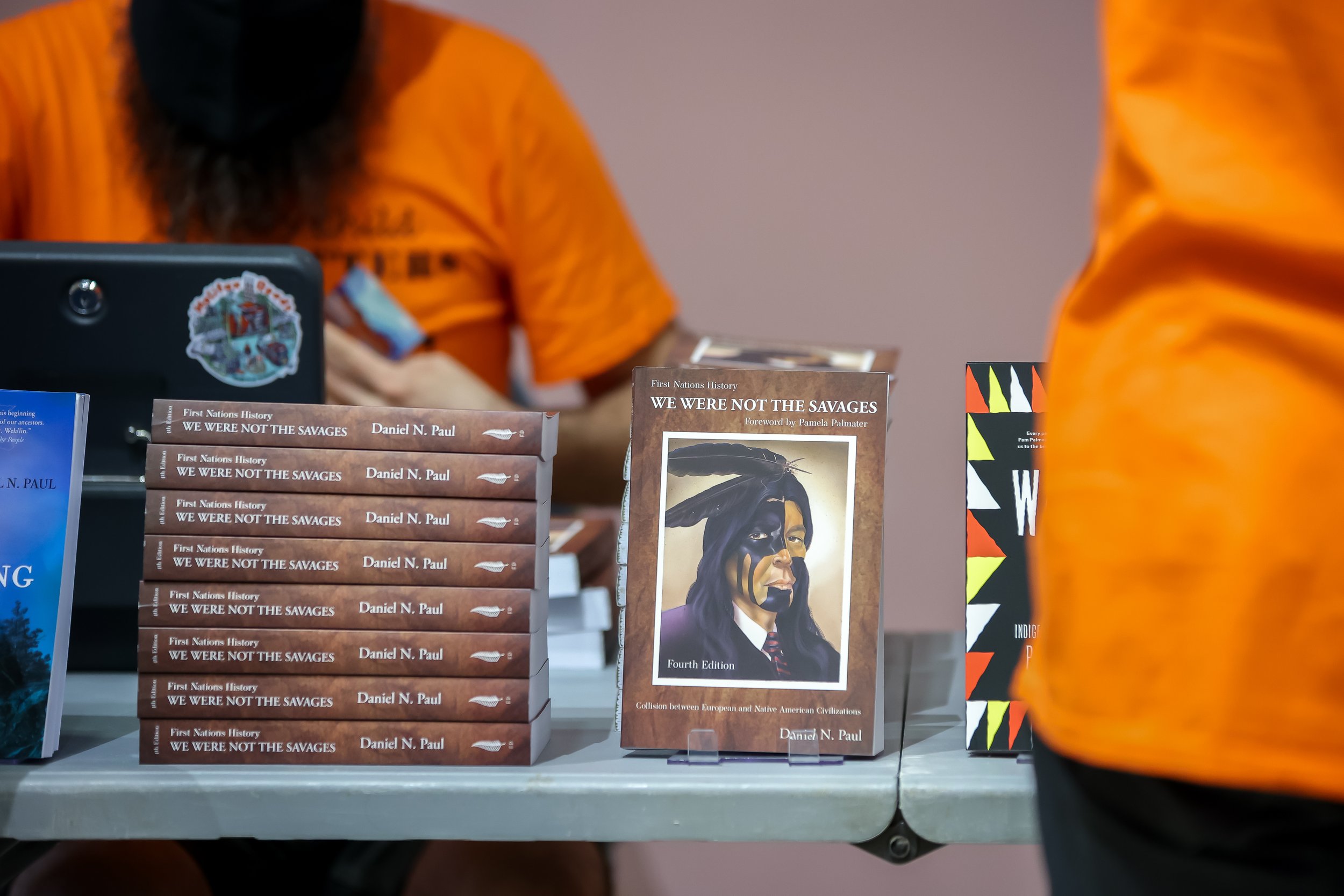

I had a sneaking suspicion, however, that this representation was not as it seemed; it seemed too good to be true that Black people would be exhibited not only as subjects but also as artists. Indeed, a quick Google search revealed that the sculptors of these busts were White, which gives the pieces a more ethnographic tone. I could not tell what the museum’s intent was, especially because contextual materials for these pieces were not readily available for the casual viewer (I chose not to pay for an audio guide). Apart from an Ethiopian king, none of the Black people depicted are named; most of the labels mention only where the subject lived, and one of the busts is described as a souvenir from an expedition. This is reminiscent of Portrait of Madeleine (1800) by Marie-Guillemine Benoist (1768-1826), a work on display in the Louvre. Originally titled Portrait of a Negress, this piece was renamed by the curators of Black Models: From Gericault to Matisse, an exhibition which opened at the Musée d’Orsay in 2019.[5] In both d’Orsay and the Louvre, Black subjects are often reduced to nameless specimens whose stories are framed in reference to their subordinate association with White Europeans.

Souvenir de voyage de l’expédition Stanley (Soudan anglais) (1900-1902) by Herbert Ward. The Musée d’Orsay. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

Femme d’Afrique centrale (around 1902) by Herbert Ward. The Musée d’Orsay. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

In sum, in both museums, whenever Blackness is allowed space in the main galleries, it is mediated by Whiteness. Ultimately, as a Black person, my visits to these world-renowned museums left me feeling othered. At the Louvre, this was mainly due to the geographical organization of their collections. If restructuring the museum is too ambitious to expect, then at least the Louvre could diversify its offerings within its existing categories, in terms of both the people being represented in the artwork, and the identities of their creators. As for the Musée d’Orsay, although Black subjects were present, they are treated as mere decoration. I believe that these busts and other pieces like them merit contextualization that isn’t behind a paywall, at least to help ensure that casual Black and non-Black visitors alike understand the histories of both the pieces themselves and the people being depicted.

Visiting these museums has fostered in me a deeper appreciation for the Apeshit video. Areujo writes that, in occupying the Louvre, “The Carters and the video’s black performers conquer a space that was not conceived to be occupied by black subjects.” Released in 2018, I saw the video for the first time as a high schooler in Toronto. Coming from a low-income family, I never imagined myself in Paris, let alone the Louvre. Flash-forward to 2023, as I walked the halls of the Louvre myself, I could tell that its designers never imagined me there either. In a world in which Black bodies and histories have been relegated to the background, any act that emphasizes the presence and agency of Black people is a revolutionary one. And so, for me, it will always be both refreshing and empowering to see a piece of popular culture in which Blackness is celebrated rather than appropriated, and Black people are revered as opposed to objectified.

Bibliography

Ménélik II, Ethiopian negus (king) (1893) by Louis-Eugène Mouchon. The Musée d’Orsay. Photo by Ta’Ziyah Jarrett.

“Black Images at Orsay Museum.” Soul of America & A World of Black Travel, https://www.soulofamerica.com/international/paris/black-images-at-orsay-museum/#:~:text=Other%20paintings%20at%20the%20Mus%C3%A9e,oil%20on%20canvas%2C%201895%29. Accessed 4 Sept. 2023.

“Black models: from Géricault to Matisse.” Musée d’Orsay, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/exhibitions/presentation/black-models-gericault-matisse-196083. Accessed 4 Sept. 2023.

Agence France-Presse. “French masterpieces renamed after black subjects in new exhibition.” The Guardian. March 26, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/mar/26/french-masterpieces-renamed-after-black-subjects-in-new-exhibition.

Araujo, Ana Lucia. “Blackening the Louvre Museum: Beyoncé, Jay Z, and the Legacies of Slavery.” A Historian’s Views, 18 June 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20230608040247/https://www.historianviews.com/?p=300. Accessed 19 July 2023.

Duncan, Carol. “Art Museums and the Ritual of Citizenship.” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, edited by Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine, 88-103. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2019.

Nelson, Charmaine. The color of stone, sculpting the black female subject in nineteenth-century America. University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Riggs, Christina. Unwrapping Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsburg Publishing, 2014.

Footnotes

[1] This article is no longer available; the link leads to a web archived version of it.

[2] Highlights of the pieces featured in Apeshit can be found on the Louvre’s website: https://www.louvre.fr/en/explore/visitor-trails/beyonce-and-jay-z-s-louvre-highlights.

[3] Christina Riggs, Unwrapping Ancient Egypt (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014), 71.

[4] Carol Duncan, “Art Museums and the Ritual of Citizenship,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine (Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 96.

[5] Agence France-Presse, “French masterpieces renamed after black subjects in new exhibition,” The Guardian, March 26, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/mar/26/french-masterpieces-renamed-after-black-subjects-in-new-exhibition.