The Insightful Dynamics of In-Person Encounters: Interviews at the Musée ilnu de Mashteuiatsh

BY KARINE L’ECUYER (Affiliate - National History and Traumatic Memory Cluster)

«Tu n'auras pas assez d'heures aujourd'hui pour regarder l'ensemble de ce qu'on fait !» / "You won't have enough hours today to see everything we do!" says Isabelle Genest, Director of the Musée ilnu de Mashteuiatsh, with a big smile.

Over the past few days, I have been spending time with the voices of the Mashteuiatsh Ilnu Museum team members as I transcribe the recordings of our conversations. In February 2024, I travelled to Mashteuiatsh, an Indigenous Community on the shores of the Pekuakami (Lac St-Jean), to meet professionals of the Musée ilnu de Mashteuiatsh. This museum opened in 1977 and has been in its current location since 1983. It is part of the Société d’histoire et d’archéologie de Mashteuiatsh, which was founded in 1976 "out of a desire on the part of the Pekuakamiulnuatsh to preserve and promote their culture."

Upon listening to these recorded interviews, I find myself smiling at the shared laughter, rich conversations, and the generosity of these museum professionals who welcomed me and offered me an overly-solicited resource: their time!

A panel in the permanent exhibition explains the Politique d'affirmation culturelle des Pekuakamiulnuatsh (Pekuakamiulnuatsh Cultural Affirmation Policy) and its underlying values for the Community. Photo: Karine L’Ecuyer.

«On est dans le milieu de la recherche, puis on le sait que c'est important qu'on participe à ce genre de recherche-là, parce que ça fait avancer les connaissances» / "We are in the research milieu, and we know it is important to take part in this kind of research because it furthers knowledge," shares Hélèna Delaunière, head of research and development services.

In the autumn of 2022, I had the opportunity to visit the Mashteuiatsh Ilnu Museum during the Société des musées du Québec's conference on Museums and the Socio-Ecological Transition. While attending the symposium, I saw Carol-Anne Plante-Côté, a former student of Montmorency College’s Applied Museum Studies program, where I work as a professor. She mentioned that she would soon be joining the Mashteuiatsh Ilnu Museum as a museum technician[1] to preserve and share Pekuakamiulnuatsh heritage.

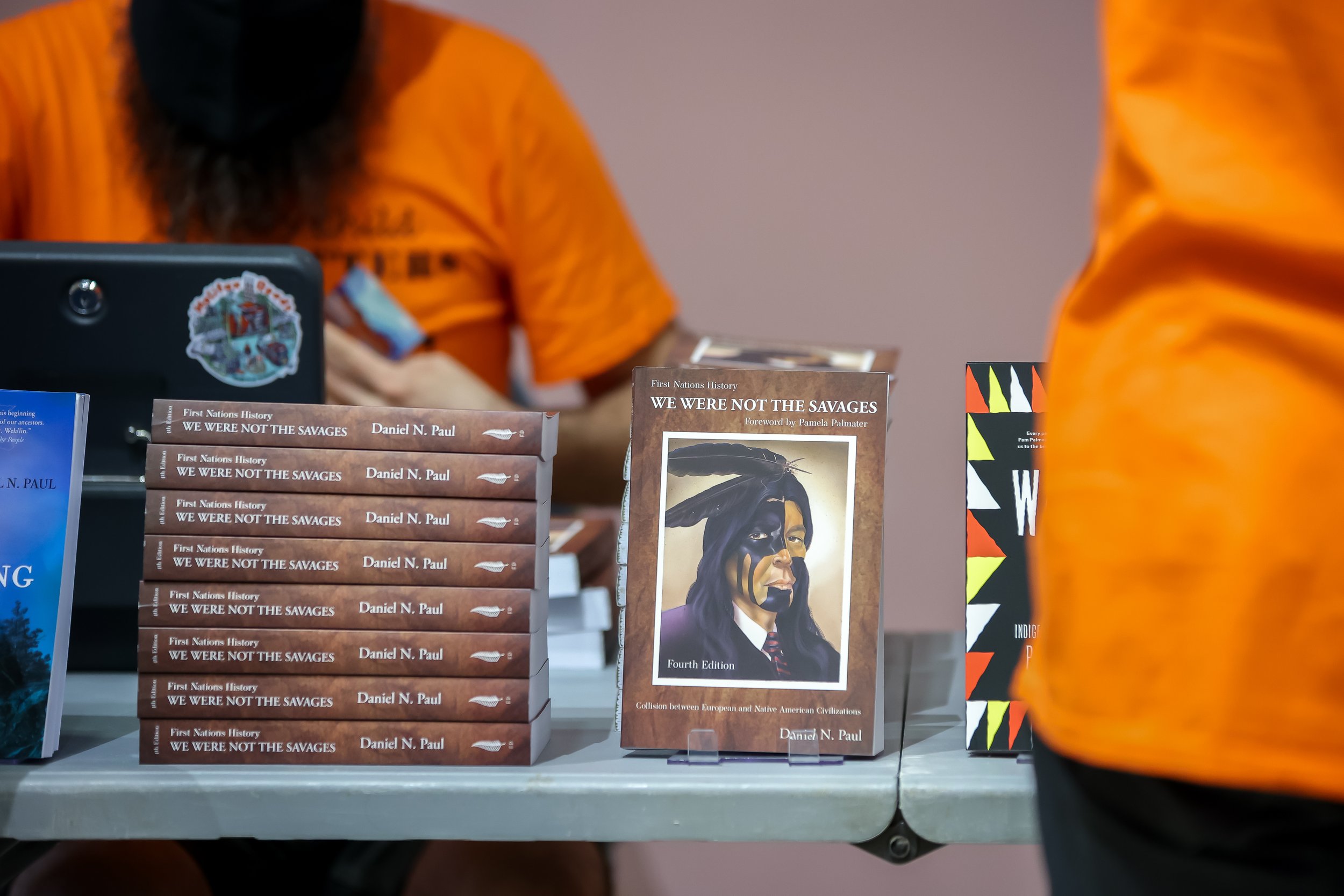

Since this exchange with Carol-Anne, I have been hoping to return to Mashteuiatsh Ilnu Museum, ethics certification in hand, to meet with the Museum’s professionals as part of the research project I am conducting on the possibilities and challenges of teaching Applied Museum Studies in a post-TRC era. I seek to explore teaching these future museum technicians as a mindful practice deliberately aimed toward reconciliation.

In January, this became a reality and I planned a trip to Mashteuiatsh to meet with the Museum’s professionals. It was only on the road, in the face of hostile winter conditions during a good part of my journey from Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal to Mashteuiatsh (465 km), that the practical idea of a virtual meeting – a possibility I had not even considered before - crossed my mind. I then realized that I had never thought of this meeting in any other way than in person. In the end, I am glad I travelled to Mashteuiatsh where I had the privilege of experiencing the rich dynamics of these encounters in person.

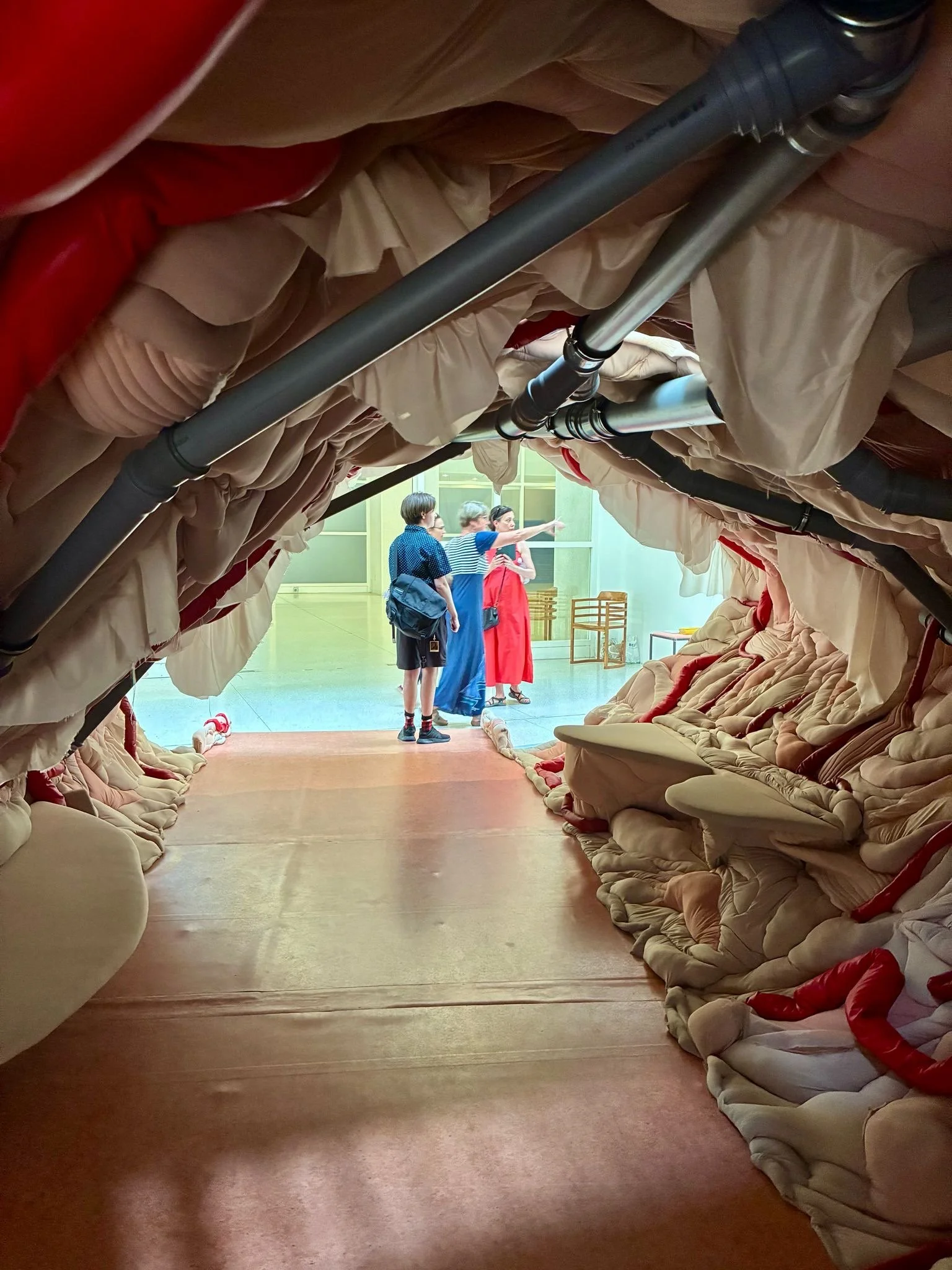

During my visit, we talked about repatriation, documentation, exhibition, conservation, traditional care, collaboration, resources, training, research, identity, reconciliation, culture, socio-political context... Through reflections, questions and observations, silences gave time to think, laughter was shared, and examples could materialize: I was introduced to a sacred mask who does not want to remain in the collection storage room; I also saw and understood some of the documentation issues related to the categorization of collections.

My visit to the Musée Ilnu de Mashteuiatsh allowed me to stroll through the permanent exhibition (part of which is available to view virtually on the Museum's website) and to see the section that is currently being redesigned, to understand the considerations for dissemination and conservation, but also the constant concern of the team: «La mise en exposition, ici, c'est un travail de communauté» / "Here, developing exhibitions is a community effort," Carol-Anne sums up. This in-person meeting also allowed me to be in the museum storage room, which doesn't have enough space for the museum’s collection. «Nos canots d'écorce, ça ne se fait plus, c'est une technique qui se perd. On ne peut même plus trouver la ressource pour les faire. On ne peut même pas les accueillir si quelqu'un nous veut nous les céder» / "Our birch bark canoes aren't made anymore; it's a technique that's being lost. We can't find the people to make them. We can't even store them if someone wants to give them to us," says Marie-Michèle Lambert, head of archives and collections, to exemplify the director's words: «les gouvernements doivent se sentir responsables ou nous aider à pouvoir avoir accès à des locaux nous permettant de gérer notre propre patrimoine.» / "governments must feel responsible or help us to have access to facilities that allow us to manage our own heritage".

Mashteuiatsh Ilnu Museum's permanent exhibition ''Tshilanu Ilnuatsh / Nous les Ilnuatsh'' (We the Ilnuatsh). Photo: Karine L’Ecuyer.

Spending time with these four museum practitioners also allowed me to feel this small team's solidarity, organic way of working, and openness despite their busy schedule. To see how they complement each other and to witness their respect and appreciation for each other. To spend a privileged moment in their company and to have the chance to see Carol-Anne where she had hoped to be since she graduated: «Je me suis fait approuver [comme nouvelle inscrite de la Première Nation des Pekuakamiulnuatsh], quasiment quand j'ai terminé les études, puis ça m'a donné un but […]. C'est à ce moment-là que je me suis dit : ʺJe veux retourner dans ma Communauté, je veux travailler au niveau de ma Communauté, puis apporter quelque chose de nouveau avec ma [formation en] Techniques de muséoʺ» / "I was accepted [as a new registrant of the Pekuakamiulnuatsh First Nation] almost at the same moment that I finished school, and that gave me a purpose [...]. That's when I said to myself: I want to return to my Community; I want to work in my Community and bring something new with my [training in] Applied Museum Studiesʺ.

I want to express my sincere gratitude to Isabelle, Hélèna, Marie-Michèle, and Carol-Anne for their warm welcome, openness, and valuable time during these insightful interviews. Committed to an ethic of participant-based, non-extractivist research, after completing the transcriptions I sent each of them to the respective interviewees so that they could review and clarify their statements, provide additional examples, or offer feedback on the research project[2]. These interviews are a significant contribution to the research project, as they provide insight into the methodologies, concerns, practices and initiatives within an Indigenous community’s museum through the voices of Indigenous museum professionals, including that of a museum technician who was my student.

These discussions have broadened, complemented, and enriched the variety of thoughts and experiences shared by other museum professionals encountered during this research project. I am grateful to everyone who has generously given their time to meet with me over the past few weeks. These moments have not only been crucial to unfolding the research project but have also already enriched my teaching, as some of the insights gained from these conversations have already found their way into the classroom.

* I sincerely thank TTTM for their support, especially Dr. Erica Lehrer and Alex Robichaud, and Dr. Jennifer Carter for her kind advice

Footnotes

[1] The three-year technical training Techniques de muséologie program grants a diploma of collegial studies awarded by le Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur du Québec. This program has been providing the Québec cultural landscape with skilled museum technicians since 1997, and their contributions have been recognized as fostering professionalism within the museum network. «Museum technician» can also be called preparator, conservation technician, museology technician, or museum objects cataloger (this is not an exhaustive list).

[2] To ensure the accuracy and respectful representation of their thoughts, the French version of this publication was first shared with the Mashteuiatsh Ilnu Museum’s professionals I met. This was done to validate the information and ensure their comfort with the dissemination of their thoughts through this blog publication.