On Emergence and Where My Research Will Live

BY MIKA CASTRO (Research Assistant - Museum Queeries)

January 29, 2025

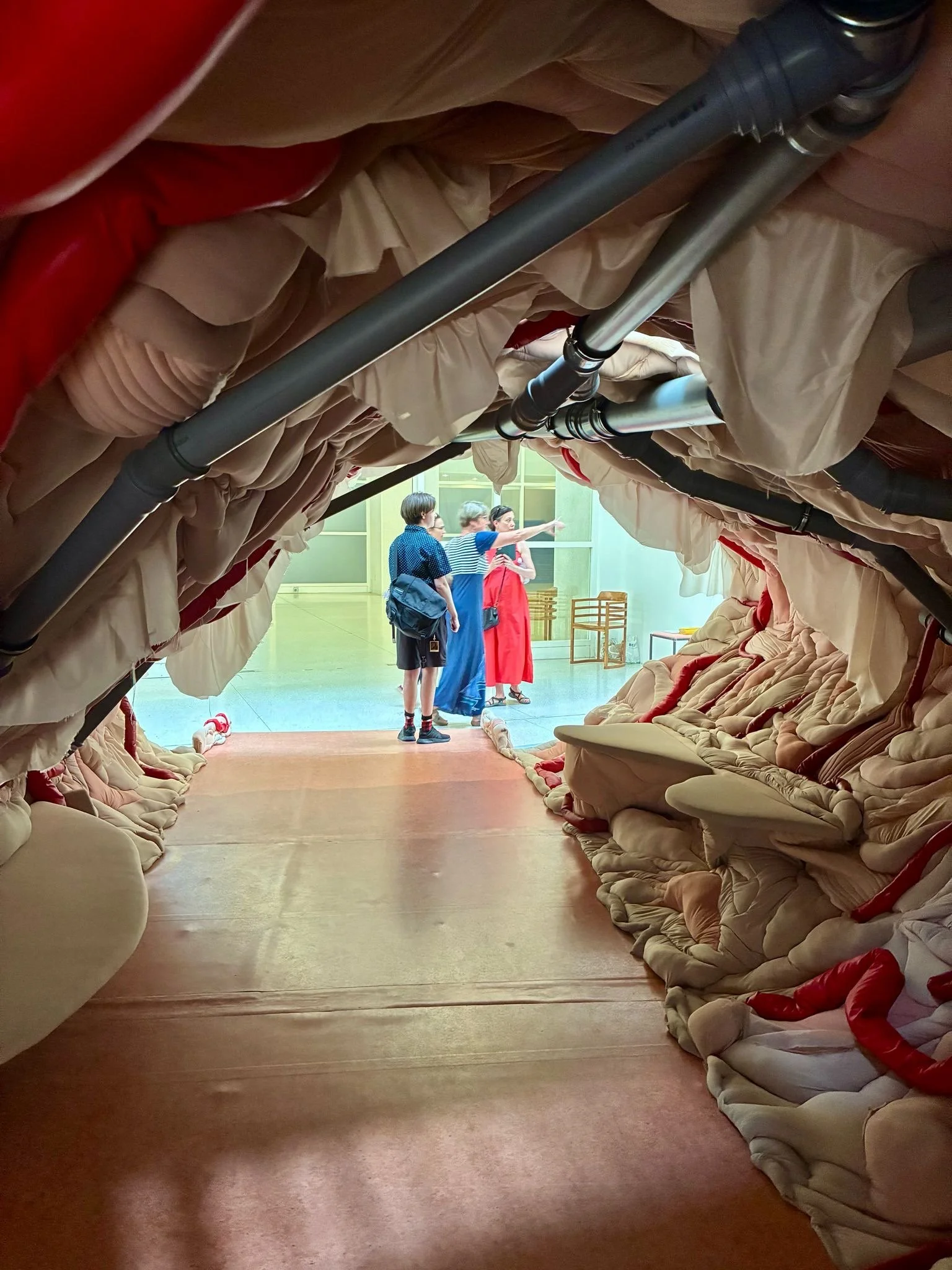

In October 2024, I was invited to fly to Ottawa to join other team members, partner staff, and local artists for the Thinking Through the Museum (TTTM) Annual Workshop, to engage in cross-cluster research, attend panels, experience the work of artists and curators, and engage in meaningful discussion around degendering museum spaces, decolonial museology practices, and so much more. On its last day I watched my fellow Emerging Scholars and Practitioners Committee (ESPC) members, the group designed to support the Research Assistants/Affiliates of TTTM, as they presented a panel on the theme of “emergence.”

ESPC members present on the topic of 'Emergence' at TTTM's Annual Gathering in Ottawa, 2024. Photo by: Keisha Cuffie.

It was the first time I have ever seen ESPC as a group present their work. Days before the panel when I checked in on some of the panelists, they humbly expressed to me their worries and their nervousness about presenting while having only spoken a little on what they were actually going to talk about. So when the panel began, I was not ready for the gut-wrenching discussions around the reality of what it is like to be an “emerging scholar” today.

The term “emerging scholar” is a SSHRC term referring to scholars who have “not yet had the opportunity to establish an extensive record of research achievement” but are “in the process of building one” (SSHRC). Although the term seems less hierarchical than "student" in the context of "student" vs. "teacher" by acknowledging that learning is flexible and not rigid, it still carries a somewhat patronizing undertone. Panelists like Hugo Rueda and Alex Robichaud, for example, discussed the weight this term still carries in academia, explaining how it still implies that one is not "there" yet, carrying a sense of illegitimacy and inexperience.

While listening to the panel, I jotted down the feelings that the panelists mentioned in their presentations. Words like “anxiety”, “fear”, and “terrifying”, came up in discussions around what it’s like to be an emerging scholar working within the current climate of academia. These words made me reflect on the overall instability and poor working conditions of academic work that many of us find ourselves and our colleagues in. It struck me then just how brave and risky it was for the panelists to speak about what emergence meant to them. To hear their anxieties spoken out loud, the very anxieties that I shared with them, with the rest of TTTM felt liberating, and I could not be any more proud of my ESPC colleagues for their presentations. TTTM’s goals for these workshops is for cross-cluster dialogue, mentorship and support, and holding space for ESPC members to identify their needs makes the TTTM project more meaningful.

As another “emerging scholar” myself, the panel generated a lot of personal questions for me around my work and position in academia. For me, if academic working conditions continue to be poor, there seems to be no end to the process of emergence for most scholars. With the competitiveness of tenure, the stress of contract-based academic work, and poor work-life balance, it could be said that many scholars today are stuck in a constant state of emergence. I ask myself, then, that if I am always going to be emerging, with very little possibility of establishing myself as a scholar, where is my research supposed to go? Where does my research exist? What directions can my academic work take outside of this timeline? Where will it live?

To answer these questions, I reflect on the work of two scholars. First is the work of Sara Ahmed, whose work makes me think of the queerness of my position as an emerging scholar. I don’t use the term queer here to note sexual deviance from the heteronormative norm, but rather as an orientation with no clear guidelines but full of abundant possibilities. Queer, Ahmed writes, is “not available as a line we can follow,” however, it is less about “finding a queer line but rather asking what our orientation toward queer moments of deviation will be” (179). Ultimately, Ahmed asks the question: “If we feel oblique, where will we find support?” (179). I feel as though the imagined promises that the end of my scholarly emergence does not sustain my work, be it stability or security. So, if my work exists outside of this academic timeline, then what and for whom am I doing it?

This is where I bring in mind adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategies.[1] These strategies are the “simple interactions” that organisers take that eventually “create complex patterns, systems, and transformations” (19). For brown, the path to change and justice is not always linear or clear, but emerging. She stresses that we remain resilient, flexible, and adaptive with our strategies, and, in doing so, we create more possibilities for social change.

Emergent strategies, in the context of my work, are about future-making, and about expanding the potential of research. I am extremely thankful for my Museum Queeries (MQ) supervisors, Angela Failler and Heather Milne, who have mentored me in my journey as an emergent scholar and who have helped me realise that research is not only for the pursuit of knowledge but also about community building—how thinking about queer migrant lives in the museum ultimately gets me to think about whose stories matter. Centering my community in my work fits into MQ’s aim of prioritising queer stories and interventions in museums, and, more broadly, fits into TTTM’s goal of developing equitable relationships between museums and the people that are represented in them.

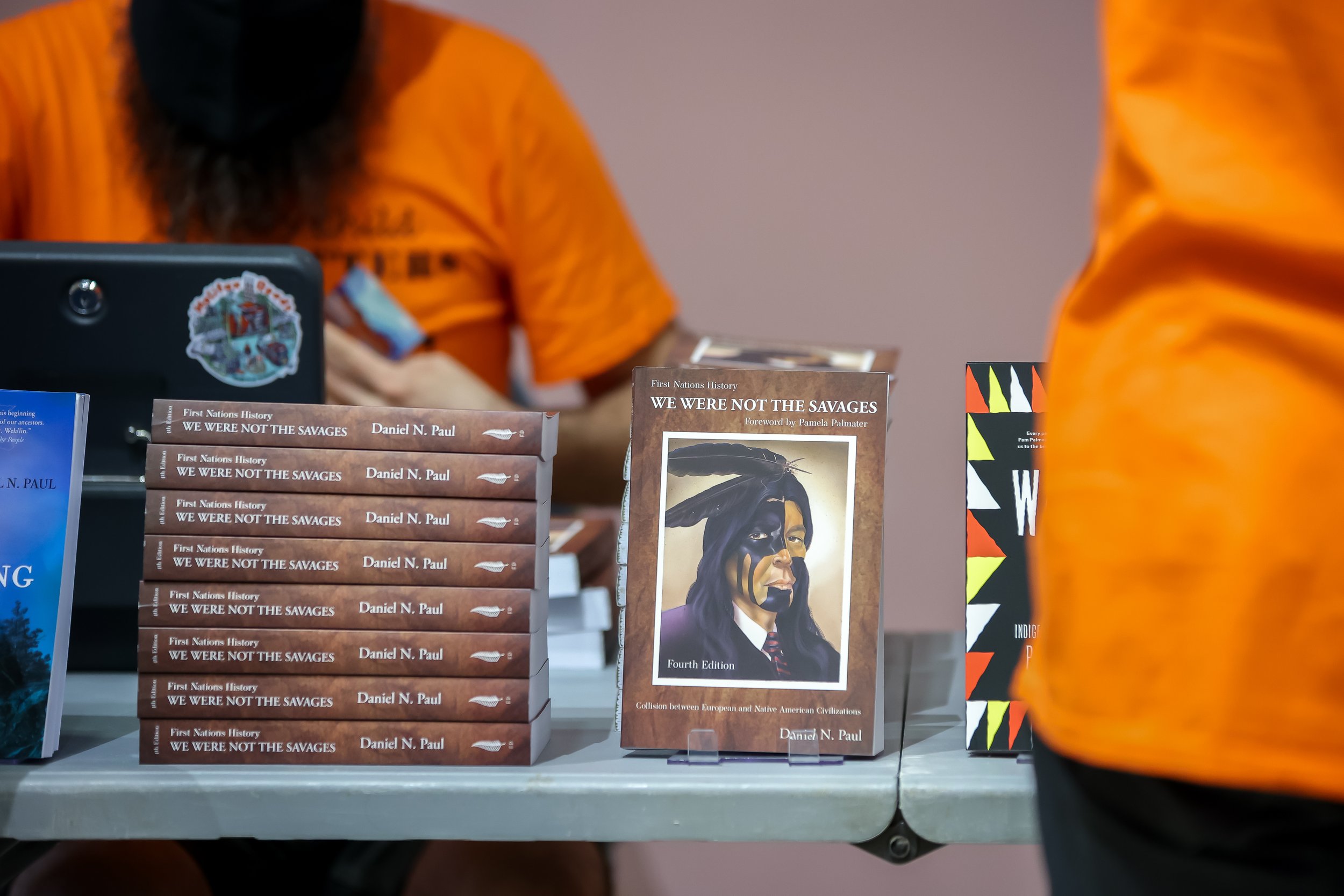

The latest coffee table setup with my dear friends at Winnipeg's Yafa Cafe. Photo by: Mika Castro.

I first began my work as a Research Assistant thinking only about the biases and the gaps embedded in the representations of Filipino migrants in Canadian museums. Later, however, through careful supervision and creative collaborations with artists and community members, I began to think about how my knowledge of these museums might help me be in better relation to my Filipino community here in Winnipeg. To bring it back to my reflections on queerness, Ahmed tells us that the “orientation toward queer” is “a way of inhabiting the world by giving ‘support’ to those whose lives and loves make them oblique, strange, and out of place” (179). This, I believe, is the heart of my research, and where my work will lead me.

When I attended this workshop, I was a week away from graduating and receiving my Master’s degree, with no plans of continuing into academia (maybe ever, or at least not anytime soon). I was worried that I was going to be perpetually stuck with the label of Emerging Scholar, and, in the eyes of SSHRC, with work that won’t ever lead me to becoming an “established scholar.” But my work with TTTM has taught me that research can live outside of such academic and institutional timelines and boundaries. Right now, my research exists in spaces like MQ and the TTTM network, but also around the coffee table, where I’ll be with my friends, my dearest research collaborators, to discuss their lives, dreams, and hopes for their lives in Winnipeg. This is where my research lives.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822388074.

brown, adrienne maree. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. AK Press, 2017.

[1] adrienne maree brown borrows her ideas on emergent strategies from Nick Obolensky, who writes about leadership. She builds her ideas using this quote by Obolensky in her book: “Emergence is the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions” (13).