On Being a Museum Scholar: Curating Research in the Field

BY KACPER DZIEKAN (Postdoctoral Fellow/Affiliate - National Heritage and Traumatic Memory Cluster)

January 13, 2025

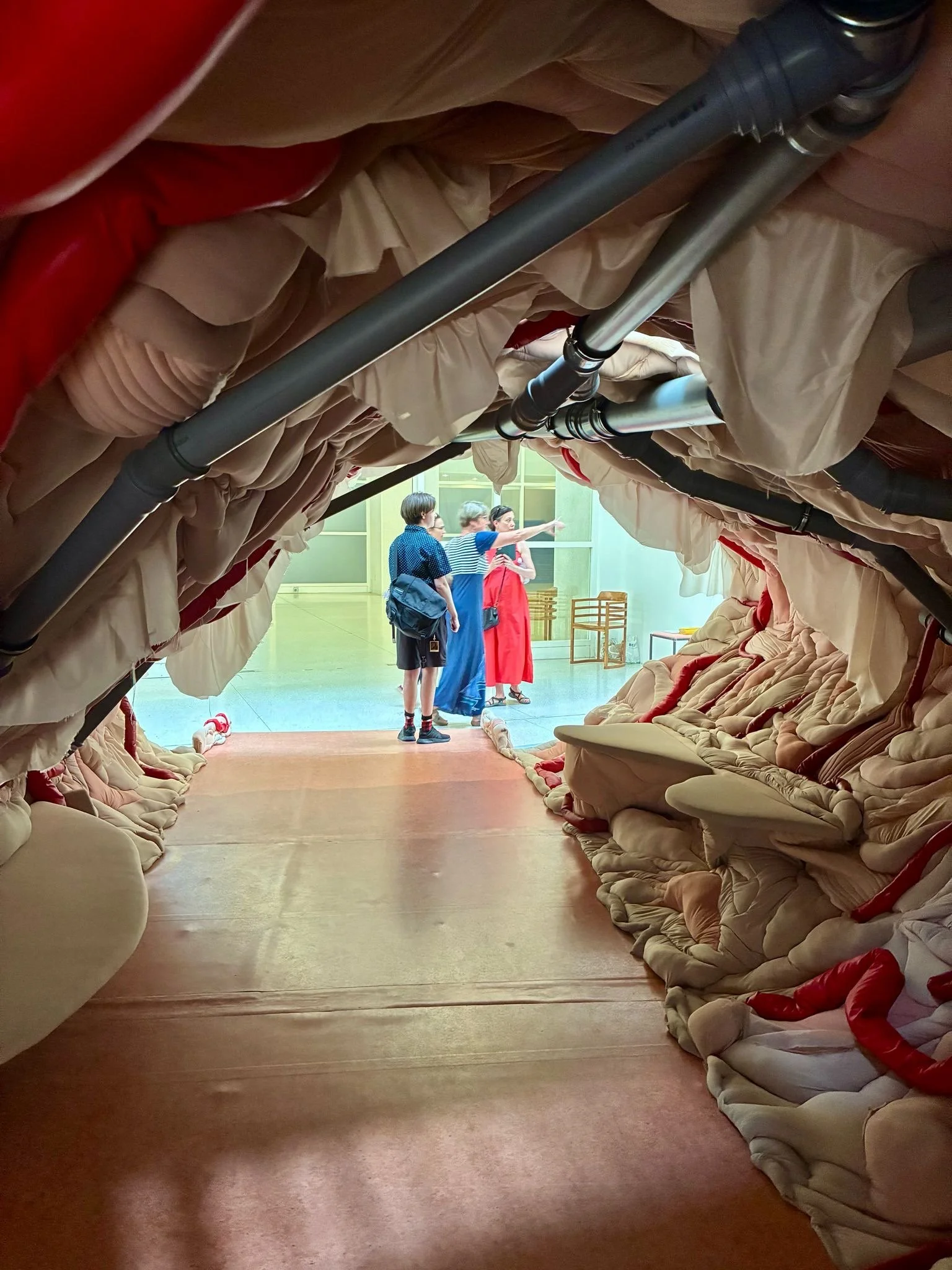

ESPC members present on the topic of 'Emergence' at TTTM's Annual Gathering in Ottawa, 2024. Photo by: Keisha Cuffie.

The panel organized by TTTM’s Emerging Scholars and Practitioners Committee (ESPC) at the annual gathering in Ottawa in October 2024 raised the question of what it might mean to be “emerging”. It was a bracing introduction to the team as a new postdoctoral fellow with the project, a role often described in terms of being an emerging scholar. What – the panelists asked – does it actually mean to be emerging? Are we always emerging in some areas? And have we arrived in others? As someone who worked for a decade in the museum world while pursing my doctoral studies, these are questions I have myself struggled with for years. They point, in fact, to a broader question: What is the role (or roles?) of scholars today in general? This question seems particularly pertinent in the field of museum studies. How does a researcher make sense of museums – their purported object of research – if they have not experienced these institutions’ inner workings? Michał Izak, Monika Kostera, and Michał Zawadzki advocate the need to return to the classical Greek meaning of education as paideia in a broad sense[1]: to develop tools and approaches to develop and engage the broadest publics with fact-based, grounded knowledge. But the big question remains: how to ensure this kind of engagement with knowledge today?

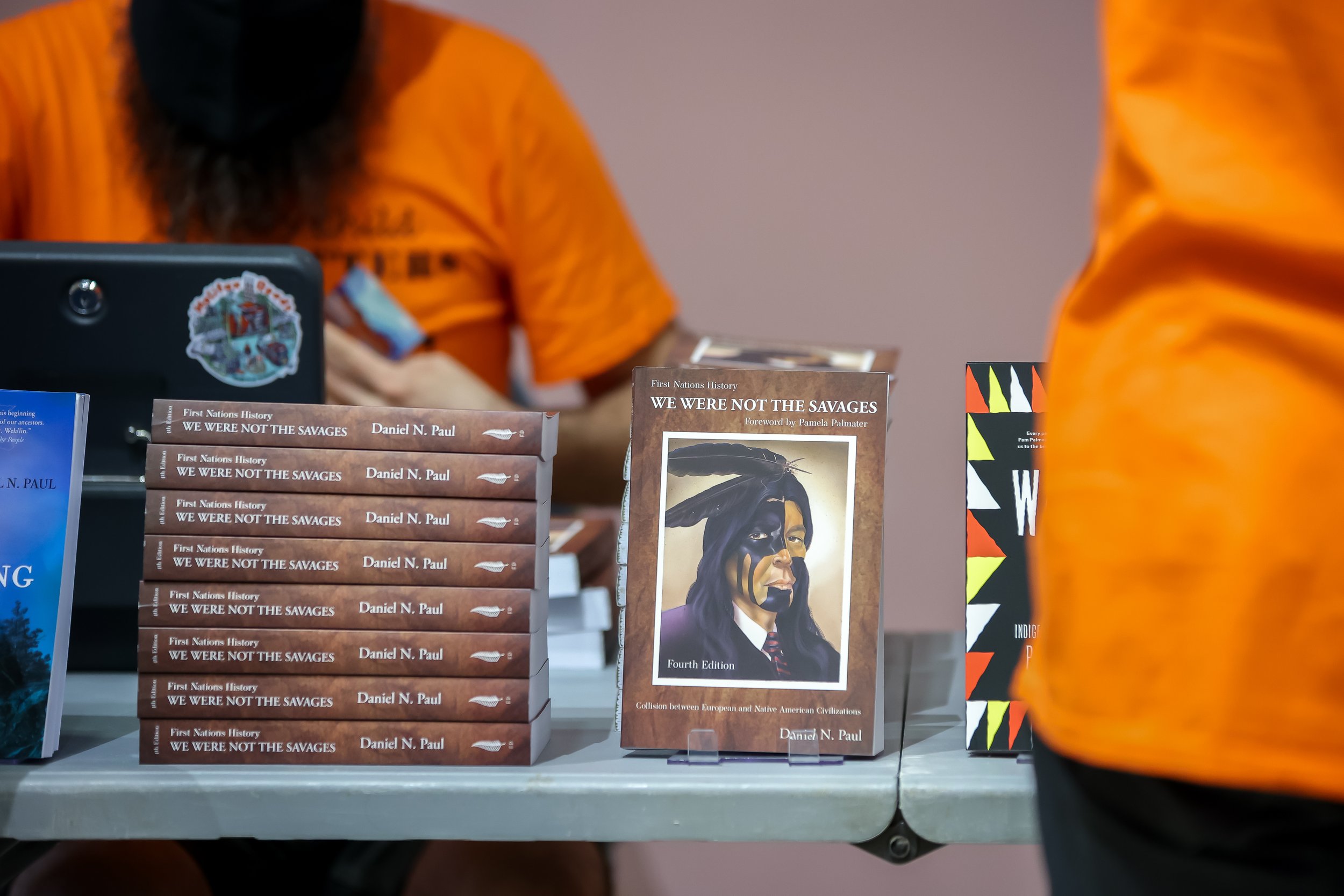

In recent years there have been increasing calls for scholars to engage more directly with the world outside of academia[2], both to contribute more to society, and to learn from the expertise possessed by non-academic actors. Such calls align well with TTTM’s mission “to explore alternative forms of heritage mobilization where communities can set their own agendas.” It is therefore crucial to engage and involve museum practitioners, artists, and activists to shape the world of museums, and the discipline of museum studies, together. But I would argue that such dialogue is not enough.

Listening to the ESPC panelists in Ottawa, hearing their challenges and obstacles, I understood that most of them had struggled in their academic careers, often forced to engage simultaneously with various forms of non-academic work. Yet, I would argue that this might be for the better. Listening between the lines, I also heard the many ways in which this “real world” work allowed them to gain experience and skills that have proved very useful in their research on museums, insight they would not have gained following a strictly traditional academic path. I was prompted to reflect on my own career, and my own “emergence”: I entered the museum world straight after completing my undergraduate studies, working there for 2 years before starting my PhD program. Indeed, I continued working at the museum all along, which resulted in my PhD studies taking longer than planned. I have never regretted it. I believe that such “insider knowledge” has helped me understand the museum world better, enabling me to craft better research questions, and to draw more robust and accurate conclusions.

Kacper Dziekan presents at a workshop at the permanent exhibition of the European Solidarity Centre. Photo by: Dawid Linkowski / ESC archive.

My sense is that the “traditional” academic career path is less and less common. I know personally a significant pool of “emerging scholars” whose professional biographies are filled with various non-academic positions. As I argue above, I consider this to be a positive turn. Universities can no longer afford to be “ivory towers”, and non-academic sectors (such as museums) are increasingly eager to get actively involved in scholarly knowledge production. Many of them now have research departments and have founded scholarly journals, which provide good career options and outlets for academically trained museum scholars. Museums more often cooperate with both universities and community experts, collaborating on research projects and creating space for the development of more rigorous and inclusive knowledge.

I would advocate for all museum scholars to take a break from academia to take a job, fellowship, or find other creative ways to engage with museums, to gain more direct knowledge of how this world works. I believe that only doing research on museums is not enough to understand how these complex institutions operate and what challenges they face. I would also encourage people to postpone scholarly careers straight after undergraduate studies, and instead to spend some time in the broader world of work before applying for a PhD. This more diverse path of “emergence” would benefit everyone: museums, universities, scholars, practitioners, and society.

References

[1] Izak, Michal & Kostera, Monika & Zawadzki, Michał. (2017). The Future of University Education, p. 7.

[2] Graham, Olivia & Griffiths, Laura & Münzner, Karla & Selak, Lorena & Barbosa, Carolina & Cai, Nicole & Ogashawara, Igor & Sun, Xinyu & Thellman, Audrey. (2024). Engaging Beyond Academia: A Call to Act for Environmental Scientists. Limnology and Oceanography Bulletin. n/a-n/a. 10.1002/lob.10667.