Whither the “Decolonial” in Decolonial Museum Discourses

BY AMY FUNG (Postdoctoral Fellow - National Heritage and Traumatic Memory Cluster)

January 17, 2025

Still from Mati Diop, Dahomey (2024, MUBI).

This past Fall, I watched Mati Diop’s Dahomey (2024), a film about the repatriation of 26 Benin Bronzes looted from the Royal Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin) by French colonists. The film, which I would describe as made in the style of documentary, but haunted by the spirit of phantasmagory, follows the Benin Bronzes as they commence their homeward journey from the Musée du quai Branly in Paris through the logistical underbelly of museum crating, shipping, condition assessments, public debates, and their ceremonial unveiling through public exhibition. Displaced for nearly 130 years from their home, the Bronzes themselves have much to say on the subject of restitution through words and voice co-written by Diop and Haitian author Makenzy Orcel.

While news stories have portrayed museum repatriation as a question of reckoning by cultural institutions, these narratives only ever allude to the uneven power imbalances as historical incidents rather than as ongoing structures. The 26 Bronzes in Dahomey (which were returned in 2021) are but a fraction of the stolen treasures from Benin alone, with thousands more displaced in museums across Europe and North America whose fates are still to be determined. In a New York Times article on decolonizing museums, this turn of physical repatriation was described by scholar Yves Bergeron as largely European, where “museum decolonization has mostly meant starting to repatriate artwork looted from former colonies. But in Canada, whose colonial history consisted of taking land from the Indigenous and suppressing their cultures, museums are changing from the inside.”

However, as Canada functions as a settler colonial society, meaning its colonial frameworks are ongoing structures of financial, social, and legal obstructions to Indigenous sovereignty, I approach any statements about institutional change from within with healthy skepticism.

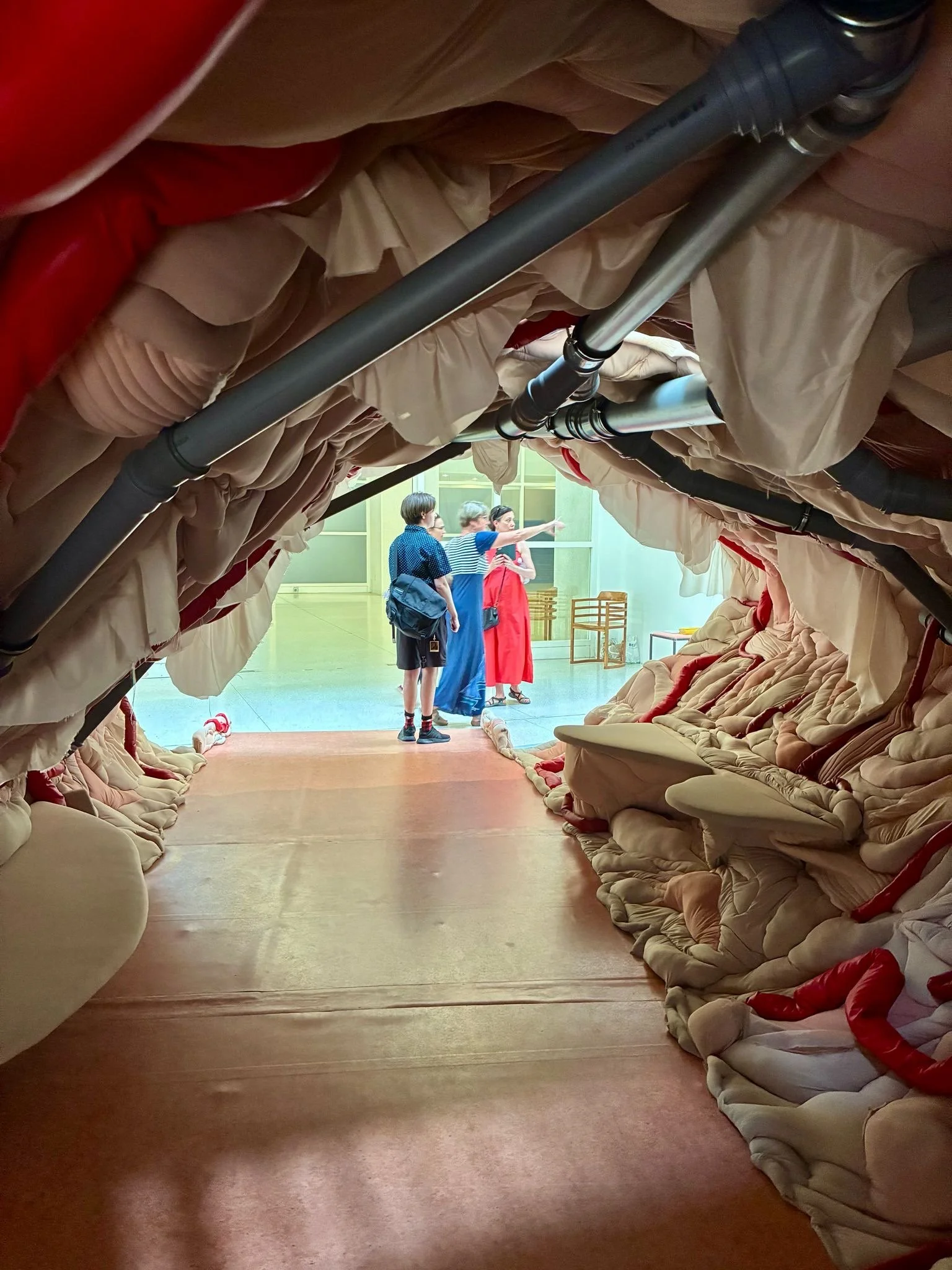

John Moses (Director, Repatriation and Indigenous Relations, Canadian Museum of History) at TTTM’s annual gathering. Photo by: Monica Patterson.

The recent gathering (October 19 - 22, 2024) of Thinking Through The Museum (TTTM) in Ottawa/Gatineau included a keynote by John Moses, Director, Repatriation and Indigenous Relations, Canadian Museum of History. He spoke to the journey of the institution from an ethnographic survey collection established in 1856 to being the first national institution in the world in 1978 to repatriate seized ceremonial and sacred works, including Potlach objects, taken by federal agents in 1922. The steady push toward decolonizing museums in Canada can be traced back to several key points, from the landmark exhibition of Indigenous self-representation by artists such as Norval Morrisseau and Alex Janvier at Expo ’67 to the national push back to the Spirit Sings exhibition, to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples released in 1996 to the final reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released in 2015. While objects continue to be returned to communities, but not power, compensation, or land, Moses, like many of the panelists and speakers at the TTTM gathering, remained highly critical of the language of “decolonization” and whether predominantly settler colonial museums can transform through policies alone.

Part of my original postdoctoral fellowship research with TTTM was to study the inaugural exhibition at the Indigenous and Canadian Art Galleries at the Art Gallery of Ontario. For context, in 2019 TTTM member Heather Igloliorte completed an extensive interview with Wanda Nanibush, co-curator of the rehang alongside Georgiana Uhlyarik, who together as the first full-time Indigenous and Canadian art curators, remapped the narrative of Canadian art through an Indigenous timeline. Their exhibition redesign was the first and possibly only time I was led to believe a museum could very well be successfully transformed from inside out short of land title cessation.

In various interviews at the time of the rehang, Nanibush spoke to the process of implementing a treaty process inside the museum as a framework for reimagining the nation to nation relationship between Indigenous and Canadian art history. In Nanibush and Uhlyarik’s vision, the natural phenomena of the country was not simply an inventory of landscapes and resources for domination and extraction, but a myriad of knowledges and epistemologies to be jointly explored by past and present communities learning to live side by side.

However, in the short period between submitting my postdoc application and being granted its award, Nanibush departed the AGO under contentious circumstances. In brief summary of The Walrus’s reporting, Nanibush was forced out from the AGO shortly after October 7, 2023 for her ongoing support for Palestinian life. According to The Walrus, the Anishinaabe curator’s advocacy for Palestinians against the daily colonial violences and humiliations as expressed through a 2016 Canadian Art article had already upset unnamed AGO Trustees, and Nanibush’s social media posts were again under scrutiny in a leaked email to the AGO’s CEO, Stephan Jost, from directors of Israel Museums and Arts, Canada describing Nanibush’s rhetoric as inflammatory and hateful. After Nanibush’s departure, counter-letters, protests, and demonstrations from the International Indigenous art community to concerned national arts professionals ensued for months. On a larger societal level, debates have continued across university campuses regarding what constitutes antisemitism, a charge that has been deeply compromised in its conflation of critiques of Israel’s war crimes with hate speech and actions against Jewish life.

These debates and discussions were present at TTTM’s workshops, where over the course of four days of panels and conversations, the palpable desire to be hired by and associated with prestigious museums and institutions and the confusion and disgust with these same institution’s treatment of people and politics was a thick and reoccurring theme. In an era of colonial and racial reckoning, the clashing of professional ambitions and interpersonal accountabilities felt acute as ever with emerging and established professionals and scholars wrestling with the praxis of decolonial theories. On one hand, material consequences have been real for many of those who choose to speak up for Palestinians. Discomfort in museum and academic spaces (ranging from who is allowed within these spaces, how they are supposed to behave, and what they are permitted to do) persists as its own form of haunting. On the other hand, laboring under censorship and retribution by museums and cultural institutions are also political choices.

Returning to Dahomey, a prolonged scene captures a vibrant student-led debate in Benin where all perspectives and opinions were heard and welcomed. Rarely on film or in life have I seen or witnessed the conversations that follow the act or policy of decolonial or equity work, where the outcome is neither benevolently given or predetermined, but where the future is still yet to be shaped by communities themselves. Rather than limiting the conversation to only those in the position to “decolonize,” Dahomey focuses on the afterlife of repatriation and decolonization where engaged youth as well as the cultural artifacts are given a voice in determining their own narratives.