The Museum as a Relationship in Progress: Reflections from the Summer Institute in Museum Studies

BY KATRINA HERMANN (TTTM Communications Coordinator)

March 14, 2024

What is a museum? Is it a collection of objects, the building itself, or the mere presence of showcase windows creating a barrier between visitors and objects? My participation in the Summer Institute in Museum Studies at Carleton University prompted me to reflect on these questions. This week-long course co-led by Alexandra Kahsenni:io Nahwegahbow and TTTM Co-Investigator Monica Eileen Patterson granted me the opportunity to learn from experts in the fields of accessibility, activism, difficult histories, repatriation/rematriation, decolonization, and children’s museology through lectures, museum visits, and discussions. The strengths of this institute lie in the diversity of museums visited, ranging from national museums (such as the Canadian Museum of History and the National Gallery of Canada) to smaller, artist-run centres (like the SAW Centre); from science and technology museums (e.g., the Science and Technology Museum) to art and historical museums (the Ottawa Art Gallery and the Canadian War Museum). At each establishment, representatives from key museum departments shared both their expertise and their ongoing struggles in collections, curation, repatriation, and educational programming. As someone who works in the museum field, the opportunity to exchange with fellow museum professionals and share insights about critical topics in museum studies provided me with much needed rejuvenation. By the end of the week, I came to understand museums in a more relational manner – that one of their greatest values exists in the interactions between the people served and the objects exhibited, and, most importantly, processes undertaken to continually improve this relationship. If museums want to embrace their inherent relationality, they must be dynamic and adaptable, instead of perpetuating practices rooted in rigidity and exclusivity.

Tactile aids in the Canadian History Hall, including a reproduction of the artifact materials and an enlarged version (Canadian Museum of History, 2024)

Getting through the door

Institute presenters reframed my appreciation of civic engagement with museums, demonstrating the nuances of what constitutes a commitment to accessibility. Kim Kilpatrick, an accessibility consultant and storyteller who is blind, shared her experiences as both a museum visitor and consultant, highlighting the importance of communication and creativity to ensure that all those who are curious to enter feel welcome. The most impactful accessibility measures she has experienced were those meaningfully crafted to meet her specific needs and interests; these could be as simple as a museum guide walking with her along the length of a whale skeleton in order to help her grasp the size of the specimen. While developing accessibility standards in collaboration with diverse consultants is vital, it is equally important that staff are encouraged to adapt these measures based on an individual’s needs (Wobbrock et. al 2011). If we view museums as existing in the interactions between publics and objects, then investing in accessibility measures cannot be viewed as optional, but rather as essential to the existence of a museum.

Justice and care for dispersed belongings

Conclusion to Shelley Niro’s exhibition, 500 Year Itch (National Gallery of Canada, 2024)

Caption reads: “Shelley Niro’s work honours many significant women in her life, such as her mother, sisters, daughters, and granddaughter. Tell us about an important woman in your life. What do you admire about her?”

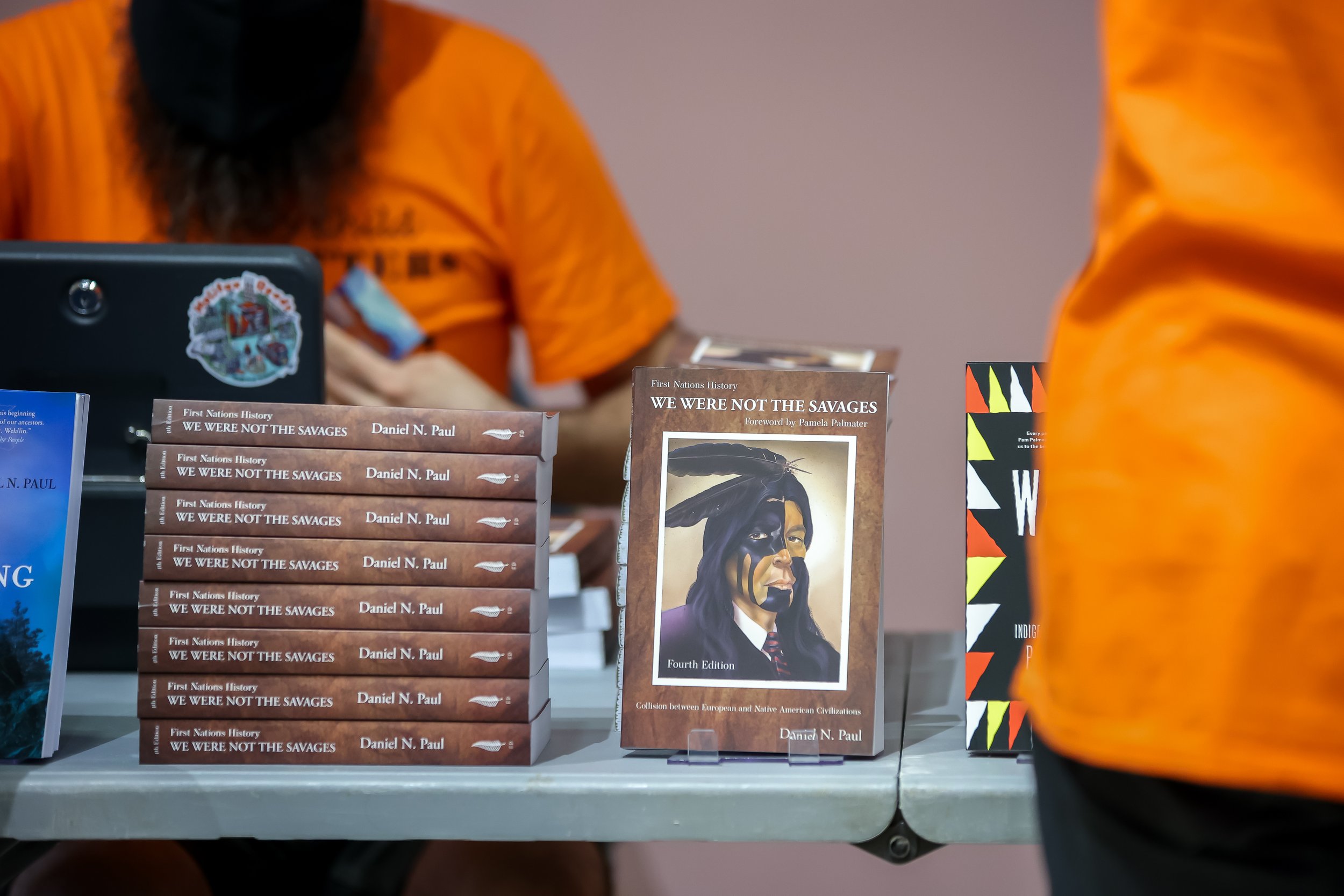

Ideas shared by convenors and participants alike expanded my understanding of the role that objects have in museums, but also the different measures that can be taken in order to adequately care for them and the communities they belong to. By centering Indigenous voices and perspectives throughout the seminar, objects were reframed as teachers that enable people to connect with their identities, histories, and communities. Certain objects are also considered living beings, which introduces a level of care required beyond traditional, sterile, Western conservation techniques (Hopkins 2020). One such example comes from the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), where Qelemteleq, “a seated stone figure with a living spirit,” is on display (Morse 2018). This ancestor of the people from the Katzie and Kwantlen First Nations of the Fraser Valley in British Columbia is treated as more than just an inanimate object due to interventions from the community. After consultation with Indigenous Advisory Committees at the NGC, practices were implemented to respect Qelemteleq’s spirit, such as putting a red blanket over the display case to allow him to sleep, so that he would feel secure during his stay in the Gallery (Morse 2018). When museums recognize their existence as dependent on the relationship between publics and objects, communities are recentered and objects are understood more deeply, providing a richer experience and shifting away from the understanding of museums as rigid and unapproachable institutions.

Museums as process

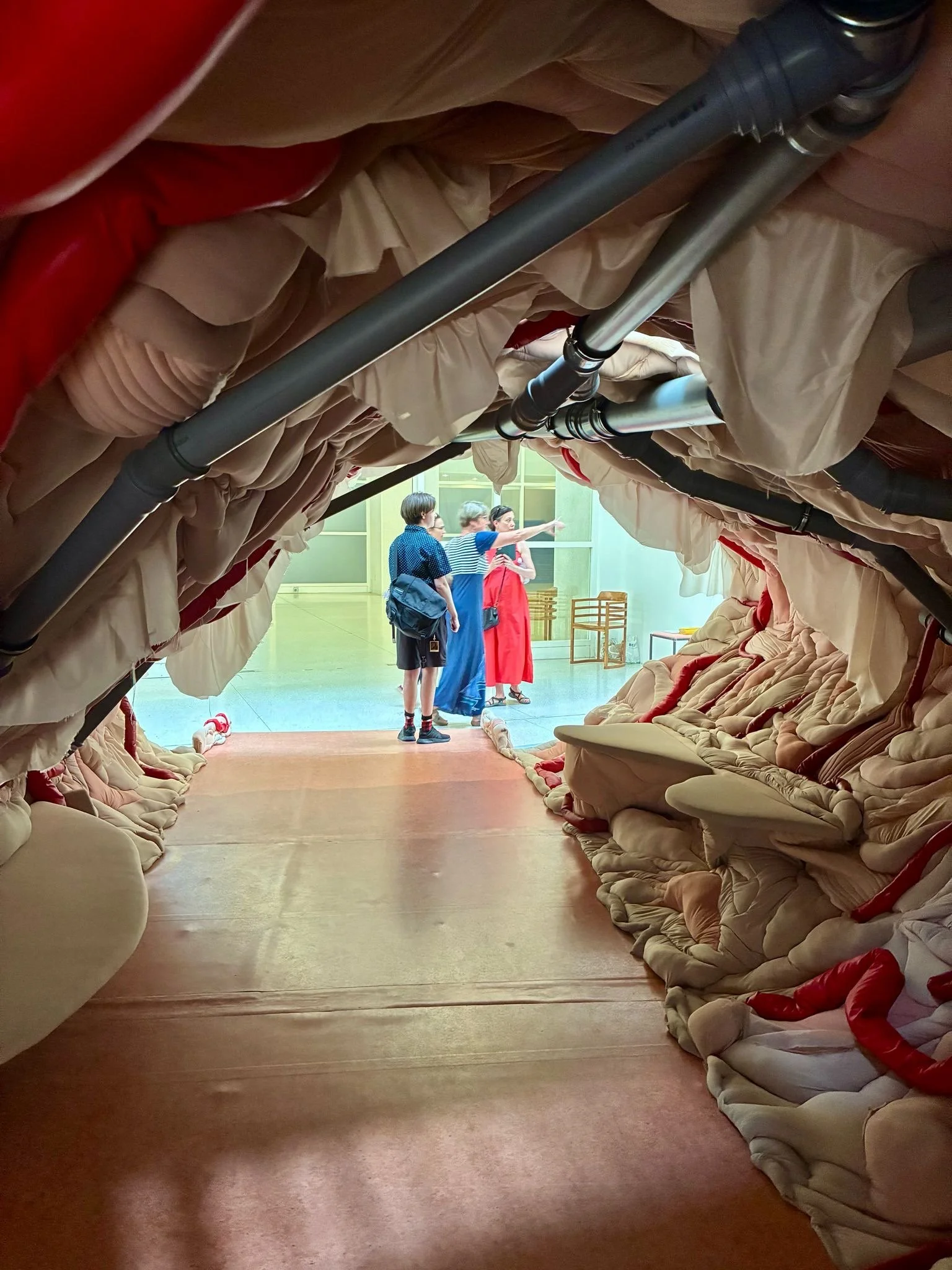

A Fine Discipline (Ottawa Art Gallery, 2024)

“Progress over perfection” was a motto of sorts that resounded throughout presentations and among participants over the week. Cara Tierney, a trans* creative/educator/consultant/curator, represented this idea in practice in their work, A Fine Discipline (2024). This work was created by Cara, Aylin Abbassi, Ash Barbu, Armin Shohrati, and fin xuan in a performance that took place on April 25, 2024 as part of the Art School Confidential exhibition at the Ottawa Art Gallery. This work explores the tensions of subverting tools that have been used to build the academy (and, by association, museums) by tearing apart art history textbooks and using these destroyed books to build a structure using bricks imprinted with the words “REST” or “RESIST.” Through this work, Cara implies that the foundations of the academy can be both oppressive but also repurposed to work towards equitable representation and liberation in these institutions. The words on the bricks speak to the importance of recognizing what Cara described as the slow arc of change required to deconstruct the undemocratic way in which knowledge is built into institutions. Working towards equity can be a form of care, even if it involves growing pains. Such discomfort signals increasing strength, allowing museums to bear greater affective and cognitive loads, increased visitor accessibility, and more support for the work of Indigenization. Museums are not, and should never be, places of fixed narratives; rather, they are institutions that become stronger through their flexibility and willingness to cultivate deep relationships between publics and objects. Museums are a process, not a destination.

Bibliography

Hopkins, Candice. “Repatriation Otherwise: How Protocols of Belonging are Shifting the Museological Fram.” Constellations: Indigenous Contemporary Art from the Americas. Mexico City: Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, 2020.

Morse, Jaime. “Guiding the Gallery: Elders, Community Members and Indigenous Experts.” National Gallery of Canada Magazine (2018).

Tierney, Cara. “A Fine Discipline.” Cara Tierney, 2024. https://www.caratierney.com/a-fine-discipline/.

Wobbrock, Jacob O., et al. “Ability-Based Design: Concept, Principles and Examples.”ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing 3, no. 3 (2011).

Wood, Elizabeth and Kiersten F. Latham. “Object Knowledge:Researching Objects in the Museum Experience.” Reconstruction 9, 1 (2009).