Braiding Stories - Walking Through Treblinka

Reposted from the Dalhousie University's OpenThink blog.

Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis: Pictured is the railway in Treblinka II, 2022.

BY KRISTA COLLIER-JARVIS

Content warning: Please note that this blog contains topics of genocide and violence that are disturbing and potentially triggering

Indigenous Métissage

This blog is an experimental embodiment of a decolonial research praxis called Indigenous Métissage. First developed by Dwayne Donald (Cree/Norwegian), Indigenous Métissage is an approach to knowledge whereby one seeks to better understand place through the braiding of stories. In braiding stories, we are asked to confront the misconception that we live in separate realities, separate places, and separate times.

Strand/Story 1

On October 12, 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was established in Nazi-occupied Poland. In November of that year, ten-foot walls topped with barbed wire were built to prevent the approximately 400,000 Jews housed within from escaping the tiny 2 km area. Overcrowding and poor nutrition (rations decreased to approximately 200 calories a day) led to the deaths of about 5,000 residents a month.

On July 22, 1942, the German SS began deportations from the Ghetto to Treblinka II, a nearby killing centre established as part of Operation Reinhard—the systematic elimination of the Jews.

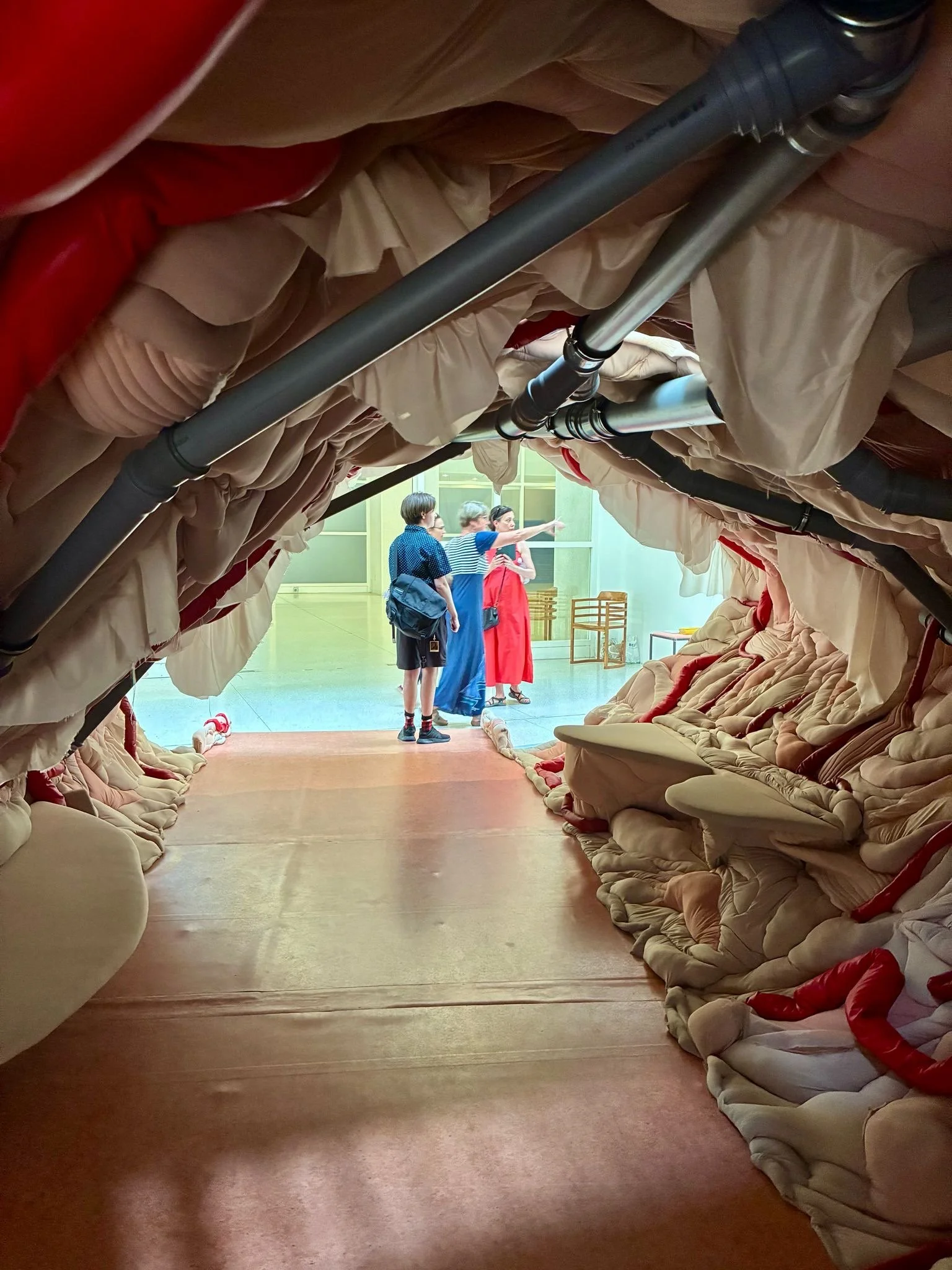

Upon arriving at Treblinka II, prisoners were met by a “train station” complete with fake signs and railway schedules. They disembarked and entered the barracks where they would undress. Upon leaving the barracks, they ran single file through a winding path framed by high hedges called the “Schlauch” (tube). Around the final turn, they faced a building, whose front door was topped with the Star of David and surrounded by flowers. Inside, a series of rooms were labelled “showers”—these were the gas chambers. All were killed.

In early 1943, the Nazis feared discovery of the mass graves, so they established open air cremation pits behind the gas chambers.

In September 1943, Treblinka II ceased operation after the deaths of approximately 925,000 Jews and an unknown number of Poles, Roma, and Soviet Prisoners of War. In 1944, all traces of the camp were destroyed. It is believed that only 67 people survivedTreblinka II.

Strand/Story 2

It takes about an hour by tour bus to get from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka.

I stand just outside where the gates would be—that is, if the gates still stood at the entrance. The air is fresh; it smells like flowers and is just the right temperature; I’ve never heard birds sing this loud. Before me stand two concrete monuments, one slightly askew as if a door has been opened. The tour guide tells us we have the choice to enter, which is something that was not afforded to the victims who lost their lives here. I enter willingly.

Across the threshold, it is as if someone has covered me with a blanket. The birds still sing, but the air is quite different—it’s heavy. I traverse forward, walking alongside the old, moss-covered slabs where the railway tracks carted thousands to their final resting place. Later, people would look at my pictures and ask if those slabs are grave markers. They may as well be. After all, many never made it this far, and their lifeless bodies were carelessly tossed from the trains between Warsaw and Treblinka.

We reach the end of the tracks and turn left, beckoned toward the massive monument that stands at the place where the gas chambers may have been—not much remains of the original camp. A smooth faced stone tells us “Never Again” in many languages. The central monument is surrounded by thousands of smaller stones. They stand at various angles, leaning in, leaning away, jagged in parts, smooth in others. No two are alike. In the distance are two massive trees, whose greenery punches the sky. They stand as guardians upon the mass graves beneath them.

I walk toward the trees and find myself stopped by a mound of dirt that extends in both directions, turns abruptly once, then twice, and re-meets several feet from me across an expanse. I stand at the edge of the pit where the bodies were burned. I refuse to photograph this part.

Strand/Story 3

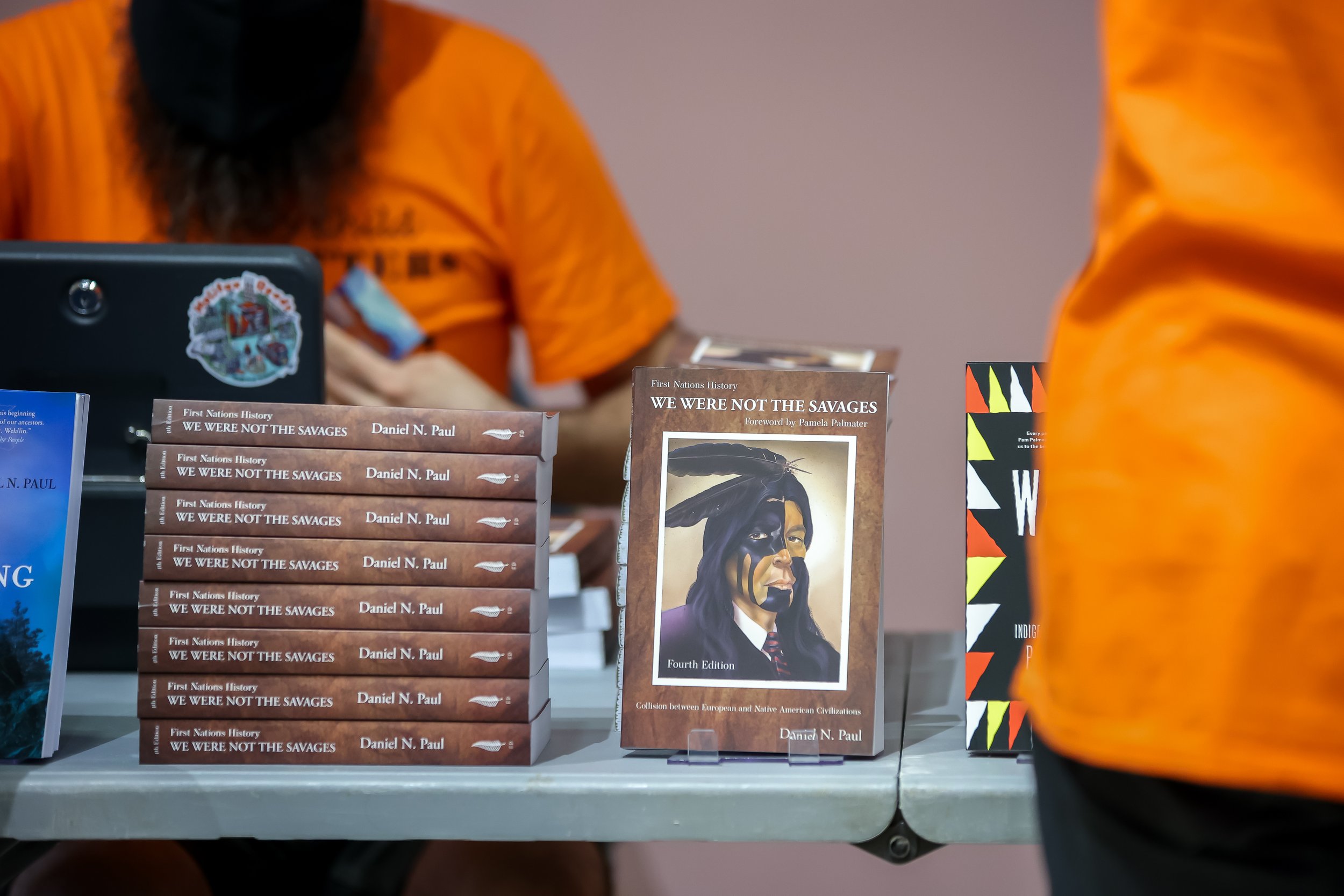

It has been one year since the remains of 215 children were confirmed using ground-penetrating radar at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Since then, 93 children were confirmed on the grounds of St Joseph Mission; 54 children at the Fort Pelly and St Phillip’s residential schools; 35 children at Muskowekwan Indian Residential School; 182 at St Eugene’s Mission School; 160 at Kuper Island Industrial School; 751 unmarked graves at Marieval Indian Residential School; and the search continues.

Excerpt from “Saving the Child within the Indian: Rethinking the Residential School Experience” (presented at Polin Muzeum on Monday, May 31, 2022)

Jeff Barnaby’s 2013 film, Rhymes for Young Ghouls, takes place on the fictional Red Crow Indian Reservation and follows Mi’kmaw protagonist Aila. After her intoxicated mother runs over and kills her little brother, Tyler, the mother hangs herself. Aila’s father takes responsibility for Tyler’s death, resulting in jailtime. He is released seven years later, but the priest of St. D’s Residential School ensures his family is punished to fulfill a personal vendetta rooted in teenage humiliation. Part of said punishment is Aila’s imprisonment within St. D’s where we watch her stripped of her clothes and her hair and see her placed in a prime position for colonial gazing—naked and powerless in a bathtub. While Bryanne Young argues that “reciting racialized injury and practices of bodily subjection” can “reinscrib[e] hegemonic formations of domination and power that made such practices possible in the first place” (68), I argue that Aila’s body resists these hegemonic re-formations during the scenes that come directly after.

In the first scene, she dreams she is walking through the forest with Tyler, who leads her to a pit full of children’s bodies. Atrocious to gaze upon, both for Aila and for us, this scene does not appeal to, and in fact, rejects the gaze. In this scene, Aila is still depicted with her long hair—revealing that the physical loss of hair does not erase the cultural embodiment of what hair represents for Indigenous peoples—it is internalized. But also, Aila’s hair rests upon her white robe in a way that looks uncannily like a priest’s garb, positing Aila as the one who embodies the colonial gaze in this moment. Aila thus reclaims these bodies and provides them the possibility of resting through her witnessing. Because “signifiers are always and already sliding along a chain of signification that is never truly fixed” (Young 71), this pit gives us a visual representation of the faceless, nameless residential school victims who have recently been found using ground penetrating radar—a technology that might also resist the colonial gaze—we can never gaze upon the actual bodies of these children, so we can only represent them.

In the second scene, Aila emerges from the school anew, but it is the spectre of her little brother, Tyler, who opens the door to her cell and leads her out. In this manner, Aila embodies Roma Sendyka’s “double self: life lived for the living and life lived for the absent” (694), for the children left in the pit, for her spectral brother, for those who never left the residential schools, and for those who still reside beneath the earth at Treblinka.

*I finish reading and look up to the rapt and supportive members of Thinking through the Museum. We still sit in the middle of what was once the Warsaw ghetto*