Innovations in Indigenizing the Gallery: An Interview with Curator Wanda Nanibush at the Art Gallery of Ontario

Photo by Kyra Kordosk (2017), courtesy of the artist.

BY HEATHER IGLOLIORTE

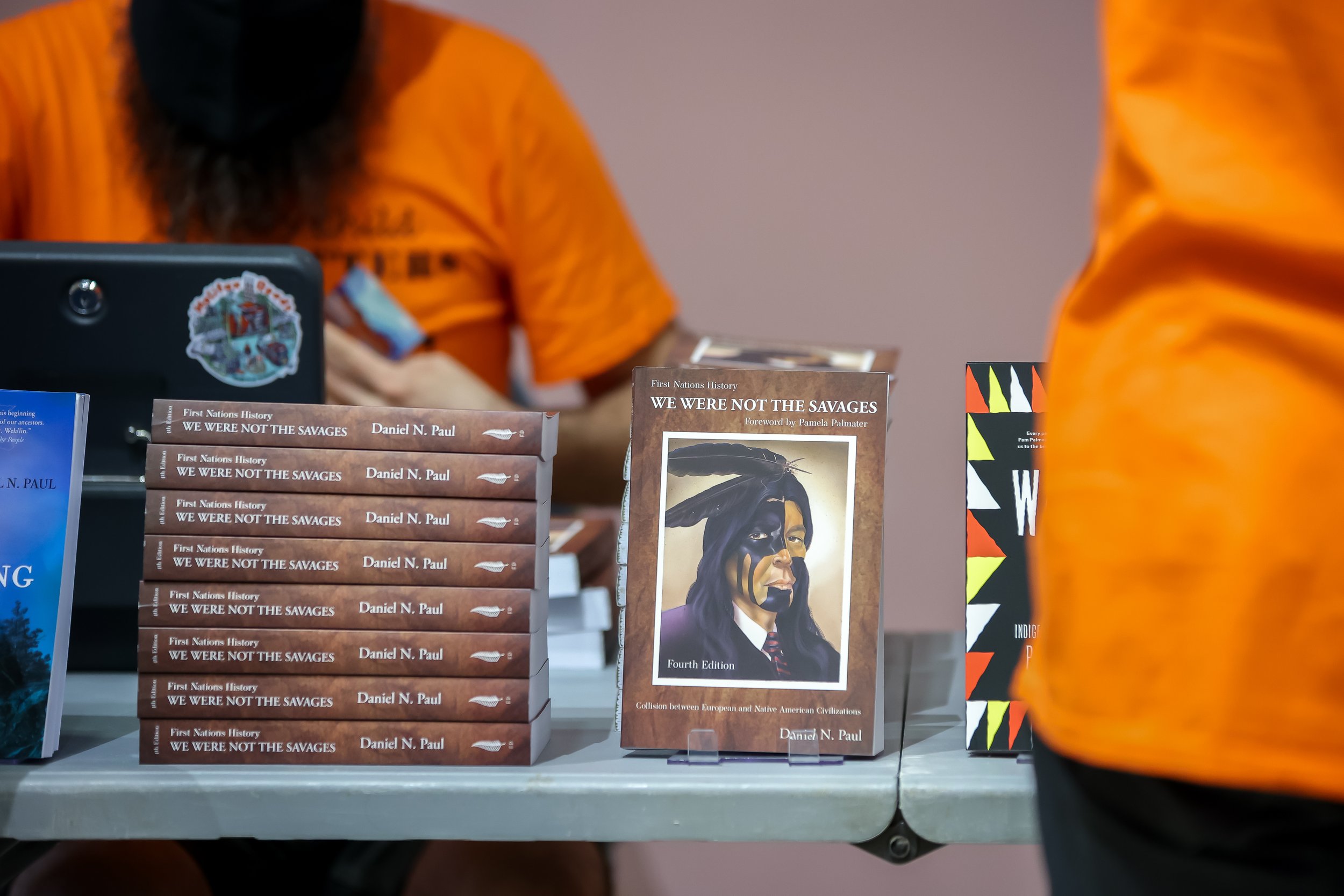

From September 13th to September 16th, 2018, the Beyond Museum Walls project took a group trip to Toronto, primarily to visit the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), which was hosting multiple events of interest to our collective research that weekend. Wanda Nanibush, the AGO’s Curator of Indigenous Art had organized the international Indigenous arts symposium aabaakwad (it clears after a storm) to take place on Friday September 14th and Saturday the 15th, which coincided with her outstanding survey exhibition Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental (July 12 - October 21, 2018). We were fortunate that Nanibush was willing to return to the gallery on Sunday morning after the symposium had just ended the night before. She gave our group of faculty and students a private tour of both the Belmore exhibition and the reinstallation of the permanent collection in The McLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art, which had recently undergone a major renovation of the individual galleries and the reinstallation of art, led by Nanibush and Georgiana Uhlyarik, the Fredrik S. Eaton Curator, Canadian Art (July 2018). Imagine our delight when Saulteaux First Nations artist Robert Houle who was meeting Wanda at the gallery for lunch, came and found us in the permanent collection galleries and treated us all to an impromptu artist talk about his paintings in the newly reopened McLean Centre.

About six months later, in June 2019, I caught up with Nanibush, whom I’ve known since the early 2000s, to interview her about some of the innovative work she shared with us and to learn more about what she had been working on since in her role as co-lead of the AGO’s department of Indigenous and Canadian art with Uhlyarik. Nanibush’s Zoom background image, which she hovered virtually in front of as we talked for a little over an hour, was our first topic of conversation.

W: My Zoom background is a photo of an event where we took Rebecca Belmore’s Wave Sound (2017-) to my reserve. The work involves listening to the water. She wanted to have the local youth involved. The folks in the photo are my nephew, niece, and brother.

H: I was gonna say, who are these cute kids in the background? [laughs] Where is this?

W: G’Chimnissing in Georgian Bay just north of Toronto. I'm lucky to be close to home, sorry [both laugh].

H: I get it. As soon as I saw your photo, I was so jealous; you can just drive to your home whenever you want. My friend and colleague Heather Campbell just moved back to Labrador and she shared a photo on Facebook and it's just a very plain image of a dirt road, and I was like, oh wow, that photo of a flat dusty, dry road really makes me homesick.

W: Ours gets dusty too; it’s all sand and dirt [laughs].

H: Alright so now that we’ve established how jealous I am that you get to work so close to your ancestral homelands, let’s talk about that work, and everything you’ve done since you started full-time at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2016. We got into that a little bit on that amazing tour of the Belmore exhibition you brought us on and I want to revisit that conversation and reflect on your work thus far.

W: One of our starting points was renaming the J.S. McLean Centre for Canadian Art, the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art, and then we rehung the entire floor on a number of principles. So one change is in the name, which acknowledges the nation-to-nation relationship. We structured the relationship between Indigenous and Canadian art based on Indigenous treaties, of peace, friendship, power sharing, non-interference, mutual respect, and working from integrity and honesty. And then I had to think about how this translates into the rehang of the permanent collection. We centered contemporary Indigenous art in all of the spaces and then the Canadian art came into the conversation in relation to the centered work. The rooms were thematically linked by a conversation on what factors go into making a citizen. We began with origins, which for us is about migration. It both accounts for Anishinaabe migration stories and accounts for the fact that Toronto is a place of migration, where people come from all over, forced and by choice. You move through Performance (the making of an identity through portraiture and performance), Land (conflicting sovereignties between First Nations and Canada), Water (how colonialism happened and is happening), Transformation (notions of spirit), and finally the Indigenous to Indigenous room (where we can do art history on our own terms). The themes are flanked by solo exhibitions of Inuit art. And of course there are many more overlapping themes in each room.

H: So essentially you decided to cover everything [laughs]. Was that work predicated on the relationship that you were building with Georgiana Uhlyarik? As in, how did you come to set up the new department and/or curatorial dialogue of Canadian and Indigenous art, which – correct me if I’m wrong – came about before the reinstallation, right?

W: I had been pushing to have an Indigenous curator as a Curator of Indigenous Art at the AGO for a couple years [Nanibush had been on contract at the AGO since 2014, then became Assistant Curator of Canadian and Indigenous Art in 2016, and Curator of Indigenous Art and co-lead of the newly named Indigenous and Canadian Art department in 2017]. I knew Georgiana was going to be promoted to Curator of Canadian Art, so I talked to our new director Stephan Jost about a new treaty model rather than a separate department of Indigenous Art. He told me to map it out with Georgiana. I am not convinced a man in her position would have been so ready to share power. We sat in the park and mapped out our new department. I also thought we needed to challenge the “Canadian” department to rethink itself in relation to Indigenous [art] but also to realize that Canada is not White. I had a long list of artists of colour that I wanted to bring into the collection after my work on the exhibition Toronto Tributes + Tributaries, 1971-1989. So we considered ourselves in a treaty relationship, and we share power, but then I take much more of a lead because we're centring Indigenous art, and she can't do that necessarily. I had just come off the streets so to speak – I had been working so hard for three years in Idle No More – so I was in that frame of mind when I came into the position, that we had to push for everything to grow and change and expand.

H: Was it a challenge to the institution? Did you have to push hard for these changes, or were they generally on board? Did you have to justify the direction you were going?

W: Yes it’s a challenge because these departments were developed in the service of nationalism, thus colonialism. To rethink the art displayed is to challenge the sovereignty of Canada and the way people see themselves as Canadian. Because the rehang was supposed to be chronological, that was what I had to push against, too. I just said to Stephan [Jost, Director and CEO of the AGO], do you want to be ahead or behind? If we start from behind, then we're gonna be playing catch up forever, and the community is never going to be satisfied. So why don't we start way ahead and then we don't have to play catch up and then I don't have to go to the community and say, “Sorry, we're only at this point.” Meaning I did not want Indigenous art as a footnote in a Canadian story. Eventually, he just had to trust us and just let us go, which he did. He's also been the buffer towards everyone who is scared of this: the folks who received their identity through all the historical [read: white] Canadian art. We weren’t getting rid of it, just resituating it with an Indigenous land and timeline.

H: Speaking of that “most revered” Canadian art, meaning the Group of Seven–era works that make up a not insignificant part of the AGO’s collections and what the audience expects to see on display when they visit the Canadian galleries, let's talk about renaming the Emily Carr painting. There were some very specific curatorial strategies that you brought into the gallery to undertake that work, and I remember when you did it, it made lots of headlines, including in the New York Times. I mean, we’ve seen other people and organizations rename things before, but usually it is, for example, an ethnographic photograph that wasn’t really “titled” by the creator but was given an offensive name while it was being categorized and then changed much later to something less loaded, like correcting a racist photo label from “Indian Squaw” to “First Nations Woman” or better, of course, that person's actual nation, community, or other affiliation. But in this instance, you were renaming an artwork, Emily Carr’s painting Indian Church (1929) to Church at Yuquot Village, which I think is why it caused such a commotion. I think there were a lot of people who clutched their pearls and thought, renaming a painting from the artist’s original title? How dare you?

W: The main point about removing racist language is to not cause harm to Indigenous audiences. That is also part of centering Indigenous in our work. We do not assume a white audience as our guide. We had already had a lot of discussion about removing racist language from artworks - for example, the word “Eskimo,” the word “Indian,” the word “Squaw.” Those are the big three that we are contending with. Before, gallery staff would keep, for example, “Eskimo,” but then put “Inuit” in brackets after it, and I said that's not enough, we need to actually just remove the racist moniker and put in “Inuit” instead. So that has been happening, but we decided, for the first actual renaming of an artwork, it would be Emily Carr’s Indian Church because we knew it would be the most controversial, the hardest one. Get ’em through the hardest part and then the rest they won't even notice, you know what I mean?

Another strategy that comes from our treaty relationship is that Georgiana has to be the one to deal with this, not me, because as an Indigenous person, it's not my problem, right? And so that is the other part: the way the treaty relationship works is that she took this on and Stephan did too, they were the ones to deal with the public anger or outrage. People assumed it was me, right, but she's in charge of Canadian art, so she has to face that [laughs]. And I think one of the lessons we learned is how much Canadian identity is tied up in this word “Indian” and in this way of thinking about us. This one woman even said, “I don't know, now I don't know where the Indians are, are they in the forest or are they in the church?” [laughs]. And I’m just like, oh my god.

H: What in the-

W: And when we contacted the community in Yuquot village for our research we found unsurprisingly that they have a complicated relationship with this church, which still stands. The church is a space where they hold ceremony – they hold their weddings and burials. So it's become kind of a community centre, but the fact that it's a church is still contentious, because of the related history of residential schools. So we centered the village [in the renaming], rather than the church. Indian Church really meant the church the ‘Indians’ use and the new title means the same.

I really believe that if Emily Carr was alive today she wouldn't use the word “Indian.” Like, I don't think she would have titled the work “Indian church” today, because from what we know about her from her writings and so on, she wasn’t ignorant of First Nations peoples. So when you think about the legacy of an artist, do you really want them to go down as just a racist? Is that what we want? Is that who she would be today? I don't think so.

H: I totally agree; when you learn about Carr in art history, sure, she is a product of her time but her story is predicated on her being respectful of and connected to these communities, and she is famous – albeit somewhat problematically – for being the one artist who wasn't actively painting Indigenous Peoples out of the landscape during that era. So then I think it’s fair to assume that she would have kept up with the times. I think that's a smart and respectful way to look at it, really. Because what are we giving to Emily Carr’s legacy by keeping this title, this old relic of a racist era in Canadian history, if we give her the benefit of the doubt, that Carr herself was not racist?

W: We bought the related work of artist Sonny Assu [Ligwiłda'xw of the Kwakwaka'wakw Nations], Re-Invaders: Digital Intervention on an Emily Carr Painting (Indian Church, 1929), 2014. We wanted to put them together so that the colonial critique that he's pulling out of her work is still present, but his response was interesting. He was worried that if you change the name, then no one’s going to criticize Carr’s work anymore. I don't know that that's true, but I think his work brings out some more things that we have to consider in relation to the original. And then Adrian Stimson's installation is in the center of that room – Old Sun (2008), which is both the name of a respected chief of his nation, the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation, to whom the artist is distantly related, as well as the name given to the residential school built on their lands by the church and Canadian state. Having that story of residential school in the center of that room of Canadian paintings, of landscape, it’s a way to tell a brand new story. It's not an intervention; it's a new history, a new story that we know but not everyone else does.

H: Another curatorial innovation, or decolonial gesture perhaps, that I wanted to discuss is something I’ve seen you implement in a particular way, and that I have noted others doing differently – but towards the same ends – as well, is in changing the way that institutions label historical works by artists whose names they do not have records of. I would say that there isn’t one right way to do it now, but there are multiple ways to do it today that seek to correct a century of doing it the wrong way. Alex Nahwegahbow at the National Gallery of Canada, for example, has labeled some of these unidentified works as “ancestor” artworks. In the exhibition I co-curated, INUA, the inaugural exhibition of Qaumajuq, the new Inuit Art Centre of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, we had about ten works lacking identification in the exhibition, and in the audioguide entry that I wrote about it I noted that we called them “as yet unidentified” and not “unknown artist.” Our thinking is, just because we do not currently have the name of the maker of a work in a collection, that doesn’t make them “unknown,” because they’re still known to us; we can recognize when something is made by an Inuk and can even often tell what family or community or region something could be from, based on the style or materials. I firmly believe that these works could therefore be identified in the future. In the catalogue, I talk about how there are so many potential signatures in our artworks, for example the distinctive way that the eyelashes are carved into a sculpture’s face, or the kind of stitch that's used around the hem of an amauti on a doll; all of that is a signature that could be read if we can just learn to recognize it. And so in INUA we were making a case for not excluding the as-yet-unidentified artists from exhibition, because I think that that's another hidden legacy of colonization in arts institutions. First, the institution shouldn’t hide away parts of the collection that they haven’t done right by; in fact, they have a great responsibility to try harder to identify them. But also, I think there is this idea that we shouldn't show these works because we don’t know the artists’ name–because it risks recapitulating past ethnohistorical museum practices of treating Indigenous artworks as the products of a primitive culture as opposed to the individual works of “genius” European artists– when my thinking now is, sometimes the more people who see these works, the more opportunity we have for someone to walk in and realize, I think my grandmother made that, you know? In the case of donations of Inuit sculpture for example, the art institutions which accept these works without knowing who made them, have an obligation to address the poor past practices of their predecessors. And without going too deep into the history of collecting Inuit art in particular, frankly a lot of these works that are not yet identified were made within the last century and could absolutely be recognized by living family members today if only they were more accessible, I am sure of it.

W: Yeah, like, for the Haida sailor that we have up, it says, “Haida artist once known,” and with the bandolier bags, it's like, “Anishinaabe artists once known,” because we know that bandolier bags, these ones in particular, probably were made by a couple of women rather than a single person. So one of the differences that I was thinking about is that “once known” means that, like you were saying, they were known and they probably could still be known today. If you stick to current art historical research methods, you'll never find out. You have to go into the community, you have to talk to people, you have to find family members, all of that kind of stuff, you know, we need to implement different research methods for that work. So it was also a way for me to signal that these people who made these works belonged to a community, and that also the artworks that they created are part of that community and part of that legacy. I kept the name “artists” and I'm pretty hardcore about that, because in our – even though they've been treated like ethnographic and anthropological examples of culture, that's not actually what they are – from all of my research and all of my talking with people, I've come to my own conclusion that people treated them like artistry, like people knew to go to Susie because she does the best embroidery on tablecloths, people knew to go to Jack because he was the best carver of Haida dolls, or whatever practice. So there is a sense of that, and I wanted to keep the name “artists” because that's how we would call these people today. I didn't want to erase that part, so I kept it, even though it's a Western word.

H: I agree it is important. This careful rephrasing serves to remind audiences in the present that there is a colonial legacy still at work here, that it is not normal that we disregarded or were careless with the names of Indigenous artists in the past, because you’d almost never see 100-year old European paintings with “unknown artist” in the gallery. It also serves to remind us about the work yet to be done.

Another thing that really struck me about all of the innovative work you are doing at the AGO came up during the tour of the McLean Centre spaces. If you recall, Robert [Houle] showed up unexpectedly towards the end of our tour, just as we were moving into the space where his works were - it was a bit magical, our good luck there. You two had a brief but really beautiful conversation about the context of his work and grounded it through his response to the 1990 Oka Resistance, otherwise known as the Kanesatake Resistance, and to the significance more broadly of land and sovereignty to his work and his legacy. Could you talk a little bit about where and why you placed Robert’s work in that space?

Robert Houle speaks with Beyond Museum Walls team members in front of his artwork “Premises for Self-Rule: Constitution Act, 1982”. Photo by Erica Lehrer.

Wanda Nanibush explaining Rebecca Belmore’s artwork “Rising to the Occasion, 1987-1991” to Beyond Museum Walls team members. Photo by Erica Lehrer.

W: The wall text for the room where Robert Houle’s work is the Land room, which talks about the competing sovereignties between First Nations and Canada, and about Canada as Indigenous land. One thing we wanted to address in the land room was this idea about the intense love for Canadian landscapes, especially by the Group of Seven, right, and how they’re devoid of Indigenous presence so they underscore ideas around Canadian nationalism and the “empty” wilderness. Because we use this centring Indigenous art model, I was like, well you know who else deals with land amazingly is Robert Houle. Robert’s paintings The Pines (2002-2004) and Premises for Self-Rule: The Constitution Act, 1982 (1994) talk about the fight for and legal basis for First Nations sovereignty. I also included In Memoriam (1987), which memorializes the nations who were exterminated through colonization. These works were alongside Lawren Harris paintings. So between Houle and Harris, you’ve got your three works that tell a huge unknown story of this country. Houle has a landscape and abstraction practice, and he admires Harris as an artist. We resituated Lawren Harris as an artist not a representative of nationhood.

One other subtle way that we address land and sovereignty is that on every single landscape in the building you will find the acknowledgement of the land depicted on the label. So on the Algonquin Park scene, it says, “unceded territory of.” On waterscapes, like if there's a sailboat in a bay – we have two that are the Bay of Fundy – it says “unceded territory of the Mi'kmaq.” So it always has the land acknowledgement, and if it's two nations that are kind of competing, we’ll put them both on the label. We say what the treaty is that covers that territory. That way an artist like Harris is not just representing ideology but the erasure of Indigenous peoples through an empty landscape is countered by the land claim in the label.

H: So, it's not just some renaming but also re-labelling works, adding more context and history.

W: Yeah, we do a ton of subtle things like that everywhere, all the time, partly because it allows people in, too. Like those who are very scared of this history, it allows them in, and it points them to a pathway to learn more without intimidating them. But it’s also a very strong statement: This is Indigenous land.

H: Did the AGO have a land acknowledgement before you came on board there?

W: They did not in exhibitions or on the walls.

H: When was that, what was your first project there?

W: I started as a guest curator with the Toronto: Tributes + Tributaries, 1971 to 1989 exhibition (2016-2017), which was a permanent collection exhibition of their 1970s and ’80s collection but done as a special exhibition which took place over eight months, and it had two iterations that were four months long each. That was the first moment they ever had a land acknowledgement on the wall. So I wrote a really long one, which actually covers all the really complicated histories of nations that have been there, and then it was also translated into Anishinaabe, so that was the first moment of translation too. It's the first thing you see when you come off the elevator, and for me it was a way, again, a subtle way of saying this is Indigenous land, Toronto.

H: Was that difficult to negotiate, or again, were they ready to move forward with this?

W: Again, I didn't ask [H: laughs]. I don't even assume that they have a problem with anything, so I just went to the woman in charge of Interpretive Planning and the head of exhibitions and said, “Hey, we need to do this.” You know, we did this with McLean too, we translated everything into Anishinaabe, and Inuktitut for all the Inuit works, right. So I just went to them and said, “Hey, we need new standards because there's gonna be two languages on the labels.” That's all I said; like, “How can you help me do this?” And that approach seemed to work.

H: Speaking of innovative approaches, the main reason why Beyond Museum Walls was in Tkaronto at that time was because you had organized the first iteration of aabaakwad (it clears after a storm), a gathering whose format I found quite lively, energizing, and inspiring. Can you tell me a little bit about the structure of the event? How did that project come about?

W: We're oral people, right, and so I was thinking about our methodology of getting together and learning. How do we learn? We tell stories, we talk to each other. We have formalized versions, but very informal versions as well. I wanted the gathering to have that feeling of visiting at the fire with each other and hanging out and, you know, it gets deep. It can get really deep, but also, we have laughter, we have intimacy. So intimacy and informality were the two things that I wanted to achieve, and then I wanted it to be Indigenous-led, so I had to invite enough Native folks that they surrounded the speakers on those front rows, so if you have a hundred Native people staring at you, you feel like you're talking to Natives, you know what I mean? That's also part of it, that's what created that intimacy and safety for the speakers. I also chose people who I know know how to speak in public, who have engaging personalities, who know how to talk about their work without a paper in front of them; not everyone in our community can do that. So it is knowing who people are, and whose personalities are gonna mix, whose personalities are not going to mix, and thankfully, I know so many people internationally and locally that I do know people's personalities to quite an extent that I could match people that way. And then we had moderators for each session just to keep it going. There were scripts; I wrote scripts for every single panel, and we had all the images just running in a slide show so that they could just flow through the conversation. The intimacy part is really important because there are things we say to each other that we wouldn't say when we're talking to an all-white crowd.

H: I didn't realize that that was your strategy at the time, but I remember in my panel, you paired me with the two Tanias – Tania Willard and Tanya Talaga – and I didn't know either very well at the time but of course I admired Talaga’s amazing and brave writing, and I’m such a superfan of Tania Williard, I have long appreciated how she brings contemporary Inuit artists into her group shows; not everybody does that, even now. So there was so much that I was like, oh my god, I'm so happy to be talking with you both on this panel. But also, for example, Adrian Stimson was a row or two back and he kept laughing really loud at something I was saying, and I felt like we were in the back of a pub in Winnipeg, instead of a room with five hundred people in it [laughs]. So, I could reveal a little bit more, and now I understand like, oh that was actually Wanda manipulating the situation [both laugh], making me feel safe because my friends are all here, so let’s get into it. That’s amazing, very effective! [both laugh] For the students we brought–which was a largely non-Indigenous group of students, although there was a couple of Indigenous people in the mix–they were all talking about how privileged they felt because they were witnessing something really beautiful and that they were learning a lot, like when you have to wash dishes after a big family dinner but then you hear all the gossip that the aunties are sharing in the kitchen. The students were towards the back, and I think that with Indigenous people to the front – wasn’t it Lido Pimienta who caused a big controversy by saying, “Indigenous people to the front of my show” and / or “Brown people to the front,” a couple of years ago? – you were kind of doing that too, like by just saying, these first three rows are for speakers, and they’re all Indigenous people. It’s amazing how effective that was actually, and it makes for a more dynamic event for everyone who's witnessing it. The other thing that you did is that there was no question period. As someone who speaks about Inuit art, I've always got the Q&A period, and you never know what's coming from the audience-

W: It can be so painful-

H: So painful. I just gave a talk, a couple of weeks ago, about the contemporary art from Labrador in INUA and the first question was, “Do your people still travel by dog team?” Like sure, but, I was talking about art [both laugh], who said anything about dog teams?

W: Yeah, I know.

H: So that was clearly a strategy of yours, not having a Q&A period in that kind of a big public forum.

W: If it's an Indigenous-led space, then I want everyone to feel safe, and question period is unsafe for all of us. At an institution the size of the AGO, you have no idea who's in the audience, there's no way to predict what's going to come out of their mouths, and so I wanted to make sure that intimacy and safety were maintained by not having a Q&A period. It also keeps the dynamic running, too, when you don't have a Q&A period. It allows the conversations to be just an hour and you can move on to the next one, because there's no time to get tired and bored. Also for the non-Native side, it's about learning deep listening. Because this is how we were raised; if we were to learn in our cultural context, we didn’t say a frickin’ word. We listen – listening listening listening, watching watching watching. And that's what I want them to learn how to do – how to be in their bodies and realize that learning actually means being quiet and listening. Learning means watching a model and learning how to do it yourself over time, and learning humility.

H: Yeah, just saying, hey audience, there's no possibility that you're going to get to ask a question, so don't worry about how you're going to center yourself in this conversation, because the opportunity is not going to come up. It's a little thing but it's a little bit revolutionary–just like, you can just listen and you're still privileged to be here–and I think that was coming through, certainly for those students we brought on the trip; that's what they were all saying: that they felt like they were witnessing something really important. And then as the audience, we actually get more. We get to see your friendships, we get to witness deep conversation.

W: I’m glad it worked. I try to do things and then afterwards assess them and go, “Okay, no to this, but yes this,” but I always take a little risk every time to see what will work. And I'll wear my mistakes, you know; I'll learn from them and I'll figure it out next time. It's like trying to bring Anishinaabe knowledge into all of the things that we do without saying it that way. I don't ever talk about it in public like, “Now I'm being Anishinaabe when I do this…” you know? But that is what's going on. And even in learning, like when you hear a story. You hear it many, many times throughout your life, and you're supposed to pick up different things that you're supposed to learn from it over time, and that can happen over twenty-five years. Like, it could be twenty-five years from now and I'll be like, “Oh my god, when they were saying this, this is what I was supposed to get out of it.” But you get that knowledge when you are supposed to, which is a very different way than the book learning way.

H: It's very true. Like when we were growing up, there was never a point where my dad would stop in the middle of doing something and say like [deep voice] “This is your Inuit teachings now,” [both laugh], but instead was like ‘chew on this, watch how I do this here, don’t touch that,’ you know what I mean? You’re just supposed to be paying attention. It wasn't until I left Labrador that I really put it in perspective, like, “Oh, not everybody is like this all the time.”

W: You have to be comfortable with being vulnerable and not knowing. I think that’s something that white society needs to understand how to do, and they're just learning it. Same thing in the art museum; you have to be comfortable not knowing and not understanding. This is why we work hard to get people into contemporary art, because it is more difficult, and so just getting people comfortable with not knowing and being vulnerable is a really good first step.

H: That is a big part of it – not fully understanding, or that it's not necessary for you to fully understand, or that you might never be in that place. I think that's a big, big shift. Speaking of big shifts, can we conclude by talking about the Belmore show as well? It's the best thing I've seen in a long, long time And like with Robert, it's also based on your long term friendship with Rebecca, right?

W: I just came to Rebecca and asked her if it's okay if we do a huge survey, and she was like, “yeah, awesome.” And then the checklist of works I had in my mind–I already had this show kind of brewing in my head–and when I showed it to her, she made no changes or additions. It was kind of amazing. We just gel so well because we've worked together so much, and I kind of love those intuitive relationships, of trust and just going with things. Then a few of the rooms came to me in dreams; you know, I curate a lot from my dreams, and I let it go. Like, I just think, whatever, yeah this is going to work; I just trust the process. But Facing the Monumental really was the impetus, because she and I had been talking so much about, like, “what the fuck is art in this moment?” We can't just keep making things for no reason; we have to take a stand. Both of us wanted to do that–me as a curator, her as an artist–and say, actually art has relevance right now, and this is one of the ways we can think about and look at and grapple with what's happening in the world, through this incredible artist’s work. The audiences were insane, and huge, and constant, and the institution didn't really know her very well and also I don’t think they even understood that this show was going to be that much of a draw. “What! This is, like, so popular!” It was brand new for the institution to think of Indigenous art like that. It’s not Picasso, it’s not Warhol, but it's as popular.

Rebecca Belmore standing next to “Facing the Monumental” exhibition introduction text. Photo courtesy of Wanda Nanibush.

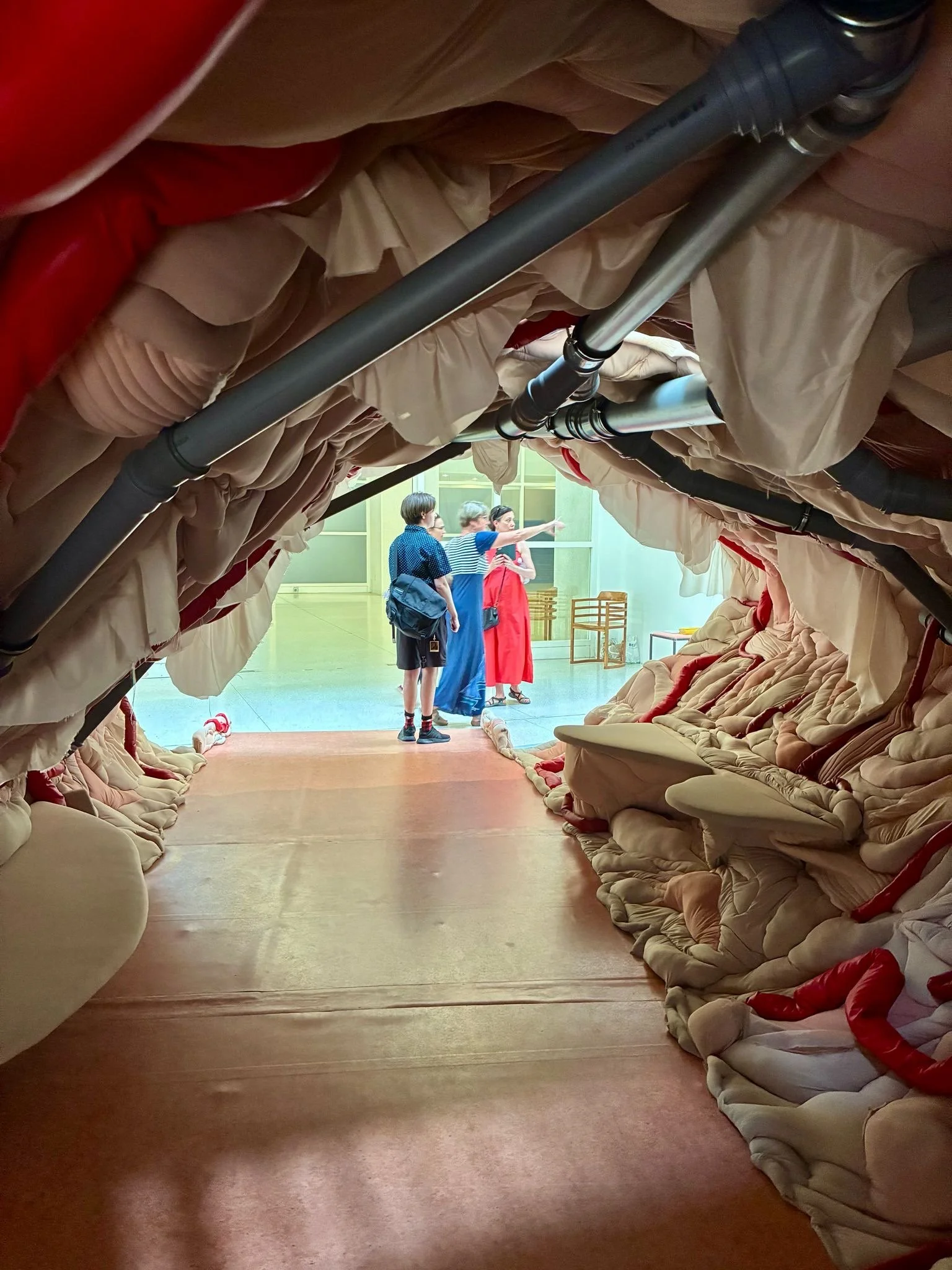

Rebecca Belmore’s “Mixed Blessing” (2012) installed as part of “Facing the Monumental”. Photo courtesy of Wanda Nanibush.

H: That's amazing, and it’s kind of wild to think that the AGO was surprised when we're all like, she's our queen! Our matriarch! It’s Rebecca Belmore, Kenojuak, and Alanis Obamsawin on top, you know? Belmore’s at the top of every kind of metric, and brilliant in every way. Her work has been making the sharpest commentary on Canada, full stop. And so for her to have that platform and to cover so many issues, from The Named and the Unnamed work, to the pieces on MMIWG [Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls], and on children, and residential schools, and to take on all that in a way that is not heavy handed but contemplative just indicates her sheer brilliance, and care; each work is an encounter. And they're sacrificing nothing in the contemporary art world to make a compelling, scathing social critique at the same time. There are very few artists in the world who can do that.

W: Rebecca is a master in the way you’ve described; I think the beauty of her work is part of how she does that. Her pieces could be so hard hitting, but they're just so fuckin’ beautiful, like her mastery of materials is just, like–to turn denim into this river, with a boy coming out–like, who thinks like that?! It's amazing.

H: Tell me about the install process, because I was enamored of the layout of the exhibition; around every corner was a revelation. It felt like the gallery was built for that show.

W: I dream about the spaces. Where there is a huge skylight in the gallery, for example, I commissioned a work for it, Tower (2018). We were touring the galleries and Rebecca’s like, “Oh I have this idea for this.” I actually learned my spatial awareness from her, because I've done so many performance art exhibitions first, so the way that performance artists work with space and site specificity is kind of what I've carried into my curatorial practice.

Facing the Monumental toured to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Montréal, the Remai Modern in Saskatoon, and it went to the Fine Arts Centre in Colorado Springs. Each time, we traveled and did the whole installation; it was tense and stressful at times because it’s a huge show and each space is so different, but each space is beautiful, and so through the new installations, different relationships, different things emerged.

H: I want to say a huge thank you to you Wanda, not only for sharing all this with us so openly in this interview but for being so generous and welcoming of our whole group during such a busy time for you at the AGO back in 2018. I think this conversation is a bit of a model of what we were talking about earlier, that we’ve invited the readers to not just read about your scholarship and practice but to sit around the fire with us, and as such get a little glimpse not just into your professional work but also who you are as a person, and our long friendship. It’s important that we laugh a lot while doing this difficult work. I feel so privileged to learn from you and I’m excited to continue to witness all the good work you’re doing. Nakummek.