“Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture” Workshop Reflections

In a groundbreaking collaboration, TTTM partnered with the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) - both in Washington, DC - on a five-day workshop (May 21 - 26, 2023) to discuss what the legacies of mass violence and oppression mean to Indigenous and Jewish people, and what they can learn from each other regarding approaches to museum collections, cultural heritage caretaking, and the preservation of historical memory.

Below are three short texts written by members of TTTM’s National Heritage and Traumatic Memory Cluster, reflecting on their experiences:

“Between a Rock and a Beautiful Place: Reflecting on the Workshop ‘Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture’” by Dorota Glowacka

“Our workshop is a garden: A methodological reflection on ‘Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture’” by jason chalmers

“Visiting My Ancestors: Cultural Care at the CRC“ by Krista Collier-Jarvis

Between a Rock and a Beautiful Place: Reflecting on the Workshop “Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture”

A Dialogue among TTTM, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the National Museum of the American Indian

Workshop participants in the freight elevator, USHMM’s Shapell Center. Photo: Erica Lehrer.

Front row, from left to right: Travis Roxlau (USHMM), Kierra Crago-Schneider (USHMM), Krista Hegburg (USHMM), Trina Cooper-Bolam (TTTM), Renata Piątkowska (POLIN Museum), Amy Groleau (NMAI), Suzanne Brown-Fleming (USHHM), Risa Arbolino (NMAI), Lauren Sieg (NMAI), Erin Bordeaux (NMAI). Back row: Krista Collier-Jarvis (TTTM), jason chalmers (TTTM), Robert Ehrenreich (USHMM); Samantha Hixson (NMAI).

BY DOROTA GLOWACKA

In 2017, I spent eight months in Washington D.C. as a fellow at the USHMM, working on the project entitled “The Intersections of Jewish and Indigenous Memories of Genocide.” I divided my time between the USHMM, the Library of Congress, and the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) Cultural Resources Center. At each institution, I met amazing people who taught me a lot about my subject. The NMAI was a fourteen-minute walk from the USHMM, yet that short distance was not reflected on the institutional level. So close and so far away, I thought. That’s how the idea of organizing the workshop between the USHMM and the NMAI was born. Until TTTM came along, that idea lingered in the realm of unrealized dreams. When the National Heritage and Traumatic Memory cluster convened in 2021, and both museums expressed enthusiastic interest, we sprang into action.

Bringing the workshop to life took two years. A dedicated group of Steering Committee members met once a month and in-between whenever wrinkles appeared in our planning. Sometimes the wrinkles felt like a tidal wave crashing against our eagerness to make this happen. But we supported one another, and we persevered despite challenges to bring the idea to life. On Sunday, May 21st, 2023, we all converged, coming from Canada, the US, and Poland, at the workshop’s welcome reception, which opened with a prayer by Elayne Silversmith, a Navajo Elder and the Branch Librarian for the Vine Deloria Jr. library at the NMAI Cultural Resources Center. We spent the next five days whole-heartedly immersed in conversations about Jewish and Indigenous experiences of genocide, individual and collective responses to violent histories, material culture linked to these histories, and the ways in which museums are implicated in colonial violence. We will be reminiscing about the wonderful things that took place during the workshop, and reflecting on those that could have been done better, for years to come.

I learned a lot in the span of those five days. But I learned just as much over the two years of preparing for the workshop. In academia today, whether we write annual reports or grant applications, we assess our successes in terms of inputs and outcomes, borrowing vocabulary from a world where everything is measured in terms of efficiency, speed, and individual achievement. But the most successful parts of our workshop were the opposite of that: they required patience and then again more patience. They meant that we had to let go of our egos, of our preconceived notions and predetermined research goals, so we could work together and open up to what we did not know and did not expect. As members of TTTM and the staff at the NMAI and the USHMM, we were coming from very different cultural, national, and institutional backgrounds, and the first thing we had to learn was to listen, with open minds, with curiosity and not appropriation, and with respect for different frames of reference and vocabularies than the ones we had been taught and were accustomed to.

I felt nourished and surrounded by kindness. I was not thinking about collecting research material, but about how wonderful it was to have those conversations with a group of amazing people, who were both so knowledgeable about their subjects and so unafraid to open up and share their vulnerabilities. I am infinitely grateful to all of them for sharing.

Our workshop is a garden:

A methodological reflection on “Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture”

jason discusses the diary of their grandmother, Melania Weissenberg/Molly Applebaum at the USHMM’s Shapell Center. Photo: Erica Lehrer.

BY JASON CHALMERS

Our first full day at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) begins in a garden. A group of us form at the museum’s staff entrance, and we are ready to begin the day’s programming with a guided tour of the exhibit Americans. But until then, we wait in a surprisingly lush and un-museum-like environment. The building’s rolling curves are set within a landscape of greenery and babbling water. Rather than sharing space with monuments and memorials, we are instead surrounded by a thriving garden. Birds rustle in the foliage and, among the diverse flora, a plot of tobacco is easily identified.

While this moment at the NMAI wasn’t part of our programming – it was only a brief repose between activities – it stands out sharply in my memory. Gardens only grow when treated with care and dirty hands, and I now suspect scholarly workshops require much of the same. As I reflect on the week, I realize that our workshop is itself a garden.

Gardeners know that good fruit begins with the right soil. Just as orchids thrive in a mixture of earth, bark, and stone, “Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture” spread its roots by drawing on several nutrient-rich sources: Thinking Through the Museum; the National Museum of the American Indian; and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. This was the first such partnership between any of these institutions, so we had to make some educated guesses. We sought the right balance for a fertile environment that would allow ideas, conversations, and relationships to blossom.

It took a long time for the seeds to germinate – at least two years, though I am told the plot was tended years before that. Monthly meetings with the steering committee created space to explore the terrain and identify productive intersections for each partner. These conversations allowed us to consider what sort of attention is necessary for handling thorny topics such as the destruction of cultural heritage, gendered violence, repatriation, unmarked burial sites, and transgenerational trauma. In addressing these topics, it became clear that our garden would require a great deal of effort and care.

For one week at the end of May, little buds – dialogues, conversations – emerged through the surface of the soil and began to reach for the sun. A welcoming ceremony on Sunday afternoon provided a nourishing drink of water. Over the following five days, participants grew together by engaging in ten interactive sessions, four guided tours of museum exhibits and collections, and myriad in-between moments over food and tea, rattling down the highway, or walking together from each moment to the next. Seeds, which contained the knowledge of preceding generations, began to realise their potential. During our final gathering on Friday, we passed a remembrance-stone and shared words from someplace deep. It struck me that our growth can only be measured by the organic mysteries of life rather than rational demarcations of time.

Some seeds remain in the soil, however. Some seeds require additional care, or time, or perhaps a different soil altogether. Which is to say that our garden has only begun to bloom. A good garden does not yield its harvest all at once, but reveals flowers and fruit from early spring to first frost and beyond. Some of this fruit bloomed and ripened in late-May, and the participants of “Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture” had the opportunity to taste the earliest offerings. But if we continue to nurture our garden – continue to feed it sunlight, water, nutrients – perhaps more seeds will bloom in their own time. If we continue to give our garden the care and attention it requires, perhaps it will continue to feed our minds and hearts.

Visiting My Ancestors: Cultural Care at the CRC

Participants of the,”Trauma, Memory, and Material Culture” workshop in the entrance to the CRC. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis.

BY KRISTA COLLIER-JARVIS

Today, I will meet the objects created by my ancestors.

I enter the Cultural Resources Center (CRC) with trepidation, nervous that the Mi’kmaq collection will not be cared for in keeping with Indigenous ways.

However, I’m immediately struck by how light and inviting and organic the space feels. Each architectural detail is clearly designed and built in collaboration with Indigenous communities. The building is shaped like a nautilus shell, and the entrance faces East, so that the first light of day can freely fill the room. There are four small glass panes in the middle of the floor as well as an opening in the ceiling to invite in both the communities of the earth and the sky.

We begin our visit in the indoor ceremonial space (there is also an outdoor ceremonial space available). The smell of the room is immediately familiar and grounding. Windows stretch along one side; their frames relegated to the furthest edges to create the feeling that the tall trees just beyond the glass are welcome. Offerings, such as medicine pouches of every size and colour, are draped along the back wall.

We proceed through several hallways into an open room where large totem and monumental poles tower over us. The smell is so natural for an indoor space as if the objects have claimed it as their own. As we traverse through rows of cabinets, the tour guide tells us that most of them do not have doors because the objects are living. They require being in the presence of other objects as well as people, and so anyone visiting Suitland, Maryland or nearby Washington, D.C. should consider a trip to the CRC.

The place where a dance headdress sat before being repatriated to the Siksika Nation. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis. Photo permission granted by the Head of Collections Care and Stewardship, NMAI.

Later, I will refuse to refer to the objects as “collections” because the work done at the CRC is not about collecting. Their primary objectives include repatriation and care. These artifacts are not necessarily meant to be preserved for posterity’s sake but are part of living cultures. As such, the Repatriation Department does exceptional work connecting with communities and ensuring that objects are either sent home or that communities visit the CRC regularly to spend time in ceremony with them.

The objects are arranged geographically and in keeping with the importance of acknowledging the four cardinal directions. We roam from the West Coast region, spending time with the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, to visit the Blackfeet, turning into “Abnaki” (Abenaki) territory, and that’s when I stop. At the end of the aisle are the objects from my Mi’kmaq ancestors.

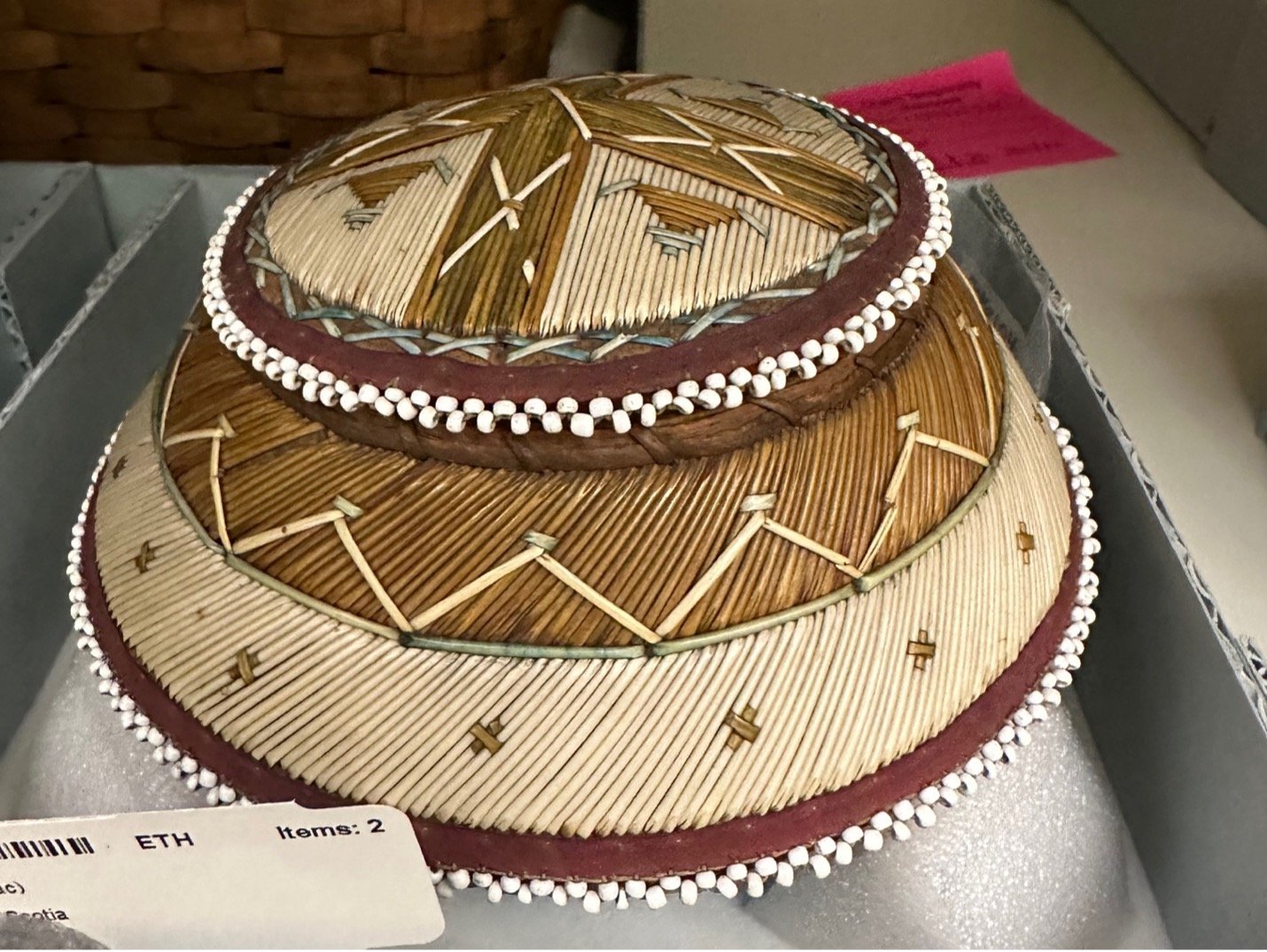

Mi’kmaq box made with birchbark, porcupine quills, and spruce root from the Rhode Island region, 1820-60. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis. Photo permission granted by the Head of Collections Care and Stewardship, NMAI.

I am suddenly filled with an intense joy.

My nervousness gives way, and I find myself leaning in closely to observe the intricate details of basket weaving, birchbark work, and quillwork—the Mi’kmaq are adept at these techniques. The designs feel familiar despite my limited understanding of the techniques and never having known their makers intimately. I can’t quite take it all in.

Mi’kmaw box made with birchbark and porcupine quills from Nova Scotia region, circa. 1850-1927. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis. Photo permission granted by the Head of Collections Care and Stewardship, NMAI.

I begin to look more closely at the dates and regions, hoping to find objects closer and closer to home. While my community affiliation is Pictou Landing, I grew up along the edge of the Millbrook Reserve in Nova Scotia. Unfortunately, the labels do not all specify exactly what community within a region to which they belong. Some are clearly identified as coming from specific areas, but most broadly identify the modern-day geographic regions.

More research into their online database reveals many artifacts and archives from my community. Perhaps I’ll seek these out on my next visit.

Mi’kmaw cradleboard made of wood from the Samiajij Miawpukek Reserve in the Newfoundland region, 1880. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis. Photo permission granted by the Head of Collections Care and Stewardship, NMAI.

Of particular interest to me is the evolution in labelling. The placards all state “Mi’kmaq,” which is the official contemporary self-label of my peoples; however, an old, yellowed tag hanging from the corner of a cradleboard from 1880 reads, “Micmac.”

When I was younger, we were called or “Micmac,” sometimes spelled “Mickmack.” Even the road I lived on was “Micmac Avenue.” Since 1760, this label has been applied as an anglicized version of our tribal name, carrying with it, of course, the history of ignoring Indigenous voices and the original names of this land. Over the years, I watched as we went from being Micmac to Mikmac, Miqmaq, Migmaw, and so on before finally becoming the Mi’kmaq.

What happened?

The language of the Mi’kmaq did not easily lend itself to the Latin or Roman script. The Mi’kmaq have a long history of writing, but we used a hieroglyphic or logographic style writing system. As the Mi’kmaq language declined amidst centuries of colonial programs, the few speakers could not write it anymore and passing on the language in its traditional hieroglyphic form became difficult.

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, writers who were trained in the English alphabet sought to include Mi’kmaq terms in their work but having no known system for writing Mi’kmaq in the Latin or Roman script, they began to experiment with phonetics, seeking to translate those oral terms onto the page.

A sample of quillwork on moose hide by Krista. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis.

In 1982, the Canadian Broadcasting Company released Mi’kmaq, a five-episode television documentary detailing the lives of the Mi’kmaq in the 1400s. This popularized the use of the term and finally acknowledged the spelling that the Mi’kmaq peoples preferred.

Thus, the old, yellowed tag, while not originally part of the cradleboard, now stands as a testament to the history of the Mi’kmaq and our search for self-determination.

Krista next to the Mi’kmaq artifacts. Photo by jason chalmers. Photo permission granted by the Head of Collections Care and Stewardship, NMAI.

*I would like to extend a special thank you to the wonderful staff at the Cultural Resources Center for welcoming me into the space and providing me the opportunity to visit these objects*