Kjipuktuk/Halifax

“Mini-Reader”

Content developed by Madeline Rae (TTTM RA), supervised by Krista Collier-Jarvis (TTTM Affiliate)

Welcome to Kjipuktuk

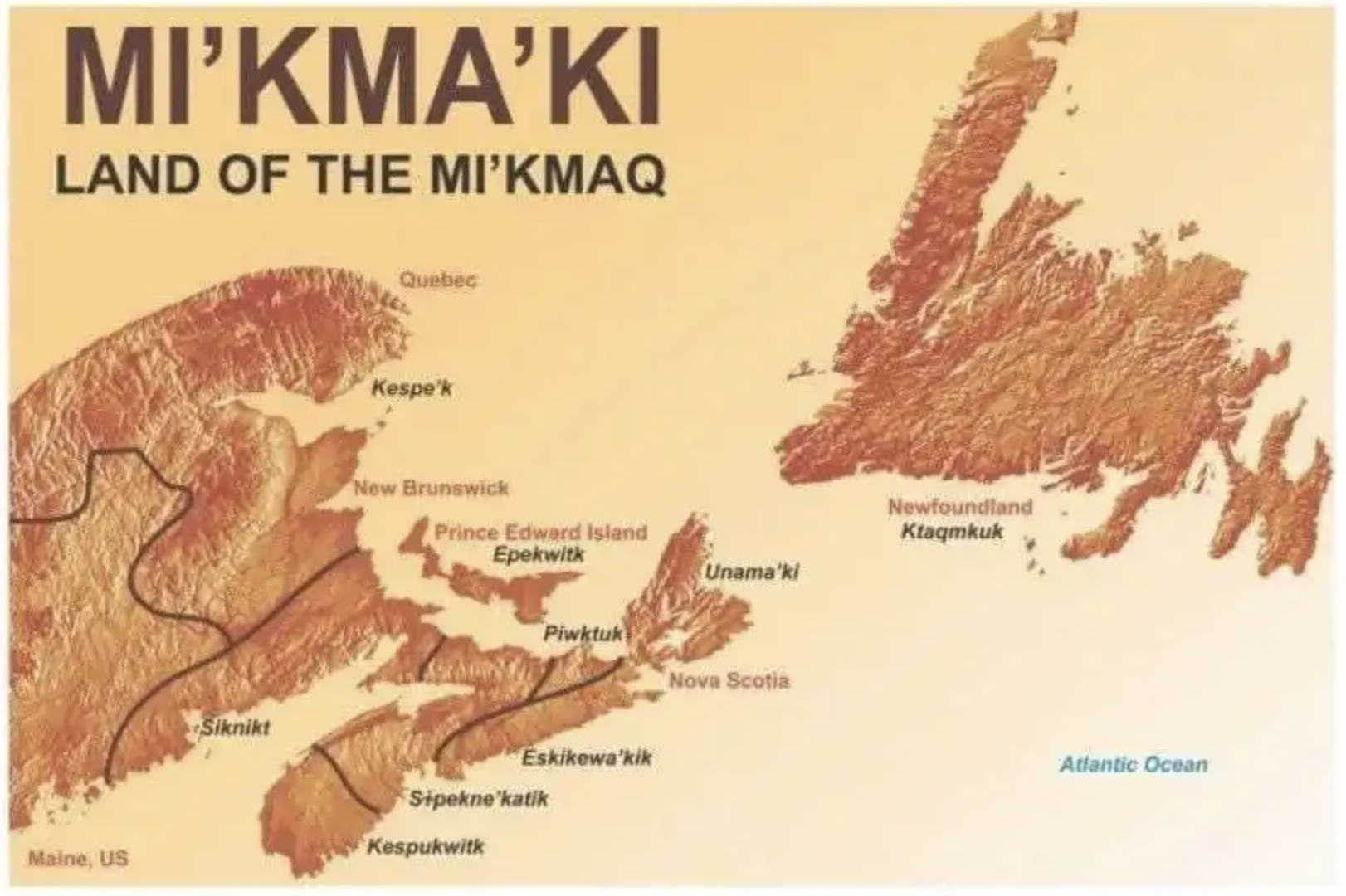

Land Acknowledgment: Nova Scotia is located in Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral unceded territory and traditional lands of the Mi’kmaq peoples. This territory, Kjipuktut/Halifax, is governed by the Peace and Friendship Treaties 1725-1779 [1]. We are all Treaty people.

Kjipuktut is the Mi’kmaq name for the Halifax area, the capital of Nova Scotia. It is one of Canada’s fastest growing cities [2], and because it contains one of the largest and deepest natural harbours in the world, it is best known for its navy and its beautiful waterfront [3]. Check out some of the many must-see attractions the city has to offer.

[1] Sarah Isabel Wallace, “Peace and Friendship Treaties”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, Government of Canada, May 30 2018, August 11 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/peace-and-friendship-treaties.

[2] Taplin, Jen, “Halifax is the Second-Fastest Growing City in the Country,” Saltwire, January 12, 2023, accessed September 6, 2023, https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/news/halifax-is-the-second-fastest-growing-city-in-the-country-100813755/#:~:text=Halifax%20is%20one%20of%20the,grew%20by%205.3%20per%20cent.

[3] McGillivray, Brett, “Halifax,” Britanica, September 5, 2023, accessed September 6, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Halifax-Nova-Scotia.

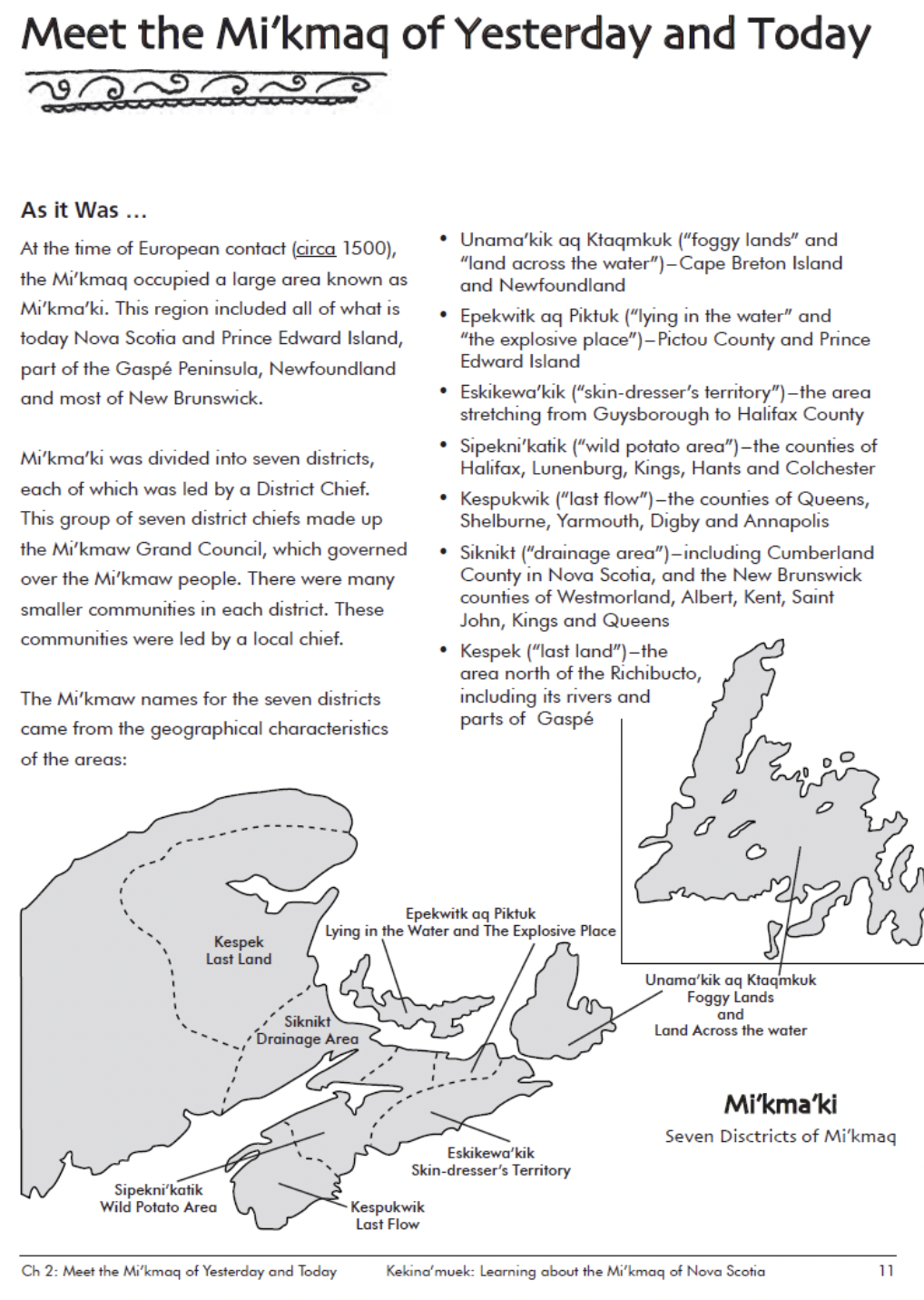

The territory of Mi’kma’ki includes modern day Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, PEI, Northern Maine, and the Gaspé Peninsula. Image from Native Land. To see what territory you live on, visit their interactive map.

Kjipuktut is home to many cultural groups and distinct histories. We have chosen to focus on 6 key topics of interest :

Mi’kmaq Land, Culture, & History

The Mi’kmaq/L’nu have been on Turtle Island (North America) for over 13,500 years. They/we are known as the quill people and their/our art, culture, and music is a pivotal part of the fabric of Kjipuktuk.

Photo of Mi’kmaq basketry at the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis.

Photo of the trunk that belonged to Angelina, who immigrated from Italy to Halifax in 1959. Photo taken by Krista Collier-Jarvis at Pier 21.

Immigration & Pier 21

Between 1928 and 1971, nearly 1,000,000 immigrants landed at Pier 21 in Canada. Now a museum, Pier 21 provides visitors a look into the journeys of many immigrants.

Photo of “Two Africville children, with Seaview African United Baptist Church and houses behind in the distance.” Photo by Bob Brooks, sources from the N.S. Archives.

Africville

Africville was a small community of primarily African Americans located on the southern shore of the Bedford Basin. Between 1964-67, the 400 plus families living in the region were forcibly relocated to make space for Halifax’s growing industries.

The progress pride flag, developed by Daniel Quasar in 2018.

2SLGBTQIA+ History & Culture

Halifax has a vibrant queer culture, including art, literature, bars/cafes, performances, and many other events. Mount Saint Vincent University is also home to one of the largest lesbian pulp fiction archives.

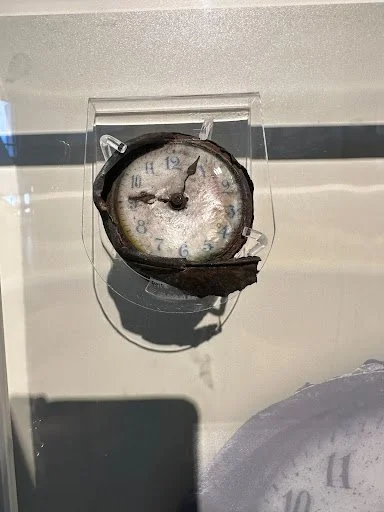

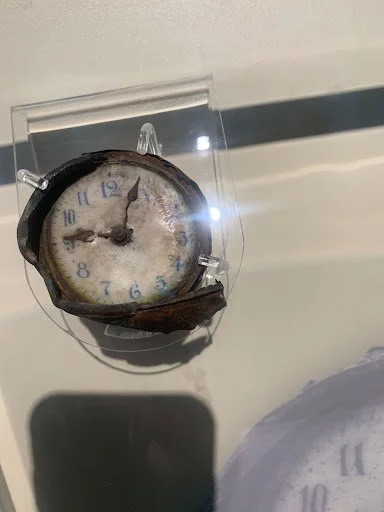

Photo of a melted clock from the Halifax Explosion. Photo taken by Krista Collier-Jarvis at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

The Halifax Explosion

At 9:04 am on December 6, 1917, the French cargo ship SS Mont-Blanc collided with the Norwegian vessel SS Imo in the Halifax harbour. The blast destroyed nearly everything within half a mile, resulting in 1,782 deaths and an additional 9,000 injuries.

Photo of the Titanic graves at the Fairview cemetery. Photographer unknown. Photo from the NS Archives.

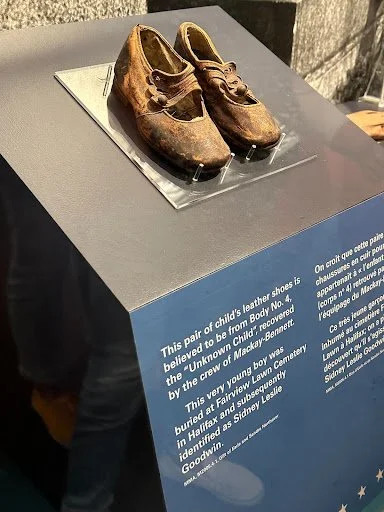

The Titanic & Halifax

On April 15, 1912, the RMS Titanic sunk. Halifax plays a unique role in this tragedy as many ships were dispatched from its harbour, returning with the bodies of the victims who are now buried in 3 cemeteries in the region. Objects from the Titanic can be found in Halifax’s Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

MI’KMAQ LAND, CULTURE, AND HISTORY

The First Nations of Nova Scotia. Image from NS Human Rights Commission [1].

The First Nations of Nova Scotia. Image from NS Human Rights Commission [1].

Peace and Friendship Treaties 1725-1779

The Peace and Friendship Treaties were signed between the Mi’kmaq peoples and the British Crown between 1725 and 1779 to protect and guarantee hunting, fishing, and the use of lands for the Indigenous peoples (Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy) who signed them as well as their ancestors [2].

“And that the said Indians shall have all favour, Friendship & Protection shewn them from this His Majesty’s Government”

The goal of the state in creating these treaties was primarily to encourage trade and prevent wars. Some Mi’kmaq had historically been allied with French colonizers against the British, and in order to try and prevent the Mi’kmaq from hostility against the British, they offered a promise to protect their land rights [3].

“And We further promise on behalf of the said Tribes We represent That the Indians shall not Molest any of His Majesties subjects or their Dependents and their Settlements already made or Lawfully to be made or in their Carrying on their Traffick or their affairs Within the said Province.”

These treaties are still in effect today, but Indigenous peoples have consistently had to fight for them to be legally enforced. The Mi’kmaq people have stood by these treaties, referring to them in the defense of their rights to fish, hunt, gather, and take ownership of their lands.

“It is agreed that the said Tribe of Indians shall not be hindered from, but have free liberty of Hunting and Fishing as usual.”

The first example of this is the 1927 case of Gabriel Sylliboy, who was charged for “out of season hunting.” Although Sylliboy defended his case with the Treaty of 1752, it was not until 2017 that the Government of Nova Scotia pardoned Sylliboy – long after his death [4[.

In 1993, Donald Marshall Jr., a member of the Membertou First Nation, was arrested for fishing eels out of season [5]. Although originally found guilty in trial, Marshall’s convictions were overturned by the Supreme Court of Canada, who acknowledged that Marshall was legally allowed to fish under the laws of the Peace and Friendship Treaties [6]. In the case of Marshall, the SCC ruled in his favor because he was hunting eel to make a “moderate living” [7]. The definition of a “moderate living” is still unclear, and the federal fisheries are still in consultation with Indigenous communities to confer on one [8].

The Treaties are protected in Canada’s constitution, and all peoples on this land are bound by them. We are all Treaty people.

To read more about the Treaties and Mi’kmaq governing structures, we recommend L’nuey [9].

Who are the Mi’kmaq?

Mi’kmaq use the term ‘L’nu/L’nuk’ to refer to themselves [11], which means “the people” [12].

The Mi’kmaq/L’nu have been on Turtle Island (North America) for over 13,500 years [13]. The earliest archeological evidence in the form of tools confirms the presence of Mi’kmaq people in the east Atlantic for over 3,500 years. Early Mi’kmaq peoples participated in hunting, fishing, gathering, and trading.

Mi’kmaq tools on display in the Kesite’tasikl: Honoring Ancestors Through Collections at Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. Photo by Madeline Rae (Aug. 2023) [14][15].

Mi’kmaq Teachings

The Mi’kmaq have many traditional and contemporary teachings that demonstrate strong relationships with the land.

The Netukulimk Exhibit at the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis (August 2023).

Seven Grandfather Teachings

The Seven Grandfather Teachings are each represented by an animal [26], and they inform how the Mi’kmaq peoples interact with one another and the land. However, they are used by many Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island (North America). Ojibway spiritual leader Edward Benton-Banai explains each teaching in his book Mishomis Book (Mishomis meaning ‘grandfather’) [27]. Below are the seven teachings in Mi’kmaq with the English translation as well as a quotation from Benton-Banai’s book:

‘Nsituo’qn / Wisdom (Beaver): “To cherish knowledge is to know wisdom”

Ks alsuti / Love (Eagle): “To know love is to know peace”

It “is very symbolic, and very important to our Indigenous culture, not just to the Mi’kmaw. I remember the Elder sharing his story, he noted, ‘have you ever seen an eagle soaring so high, then it just kind of disappeared?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I did!’ And at that time, it left our world and went to the spirit world and sat in the lap of the Creator, and delivered its messages, and when it leaves, that’s when it pops up in our world and you see it again. I remember, I said, “Yes I did,” seeing the eagle once again. That’s where the eagle feather comes into play when we do our smudging, but when we do our prayers, we use an eagle feather, because the eagle delivers the prayers and messages to the Creator” (Mi’kmaw educator from Eskasoni First Nation Trevor Sanipass for CBC) [28].

Kepmite’taqn / Respect (Buffalo): “To honour Creation is to have respect”

Mlkita’suti / Courage (Bear): “Bravery [Courage] is to face the foe with integrity”

Koqqwaja’taqn / Honesty (Sabe/Sasquatch): “Honesty in facing a situation is to be brave”

Nutajite’lsuti / Humility (Wolf): “Humility is to know yourself as a sacred part of Creation”

Ketlamapukuek / Truth (Turtle): “Truth is to know all these things”

Display at Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History exhibit of Mi’kmaw quilt, depicting the eight-pointed star with the four colours. Photo taken by Madeline Rae (August 2023).

Medicine Wheel

Jeff Ward (Mi’kmaq) explains that medicine wheel teachings vary depending on the community and contain many teachings [38]. He says the medicine wheel can represent many things, such as the life cycle, stones around a fire or sweat lodge, the inside of a drum, mother earth, seasons, and more [39]. Ward says that his teachings and ceremonies say that east is yellow, blue/black is south, red in the west, and white in the north [40].

Image from the Benoit First Nation (August 11 2023).

Anko’temej / let us take care

Display at Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History exhibit “Kepmite’tmu’kik pitul-kniskamijinaqik Mawo’tawniktuk: Honoring Ancestors Through Collections.” Image shows a traditional Mi’kmaw woven basket used to carry medicines. Photo by Madeline Rae (August 2023).

Display of a traditional Mi’kmaw basket with quillwork design in the eight-pointed star on display at Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History exhibit “Kepmite’tmu’kik pitul-kniskamijinaqik Mawo’tawniktuk: Honoring Ancestors Through Collections.” Photo by Madeline Rae (August 2023).

Chief Malti Pictou’s birch bark Canoe on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Measuring 4.7mm, Chief Pictou used his canoe to hunt porpoise’s in the Bay of Fundy, 1890-1920. In 1936, Matthew Pictou used the canoe in Twilight of Micmac Porpoise Hunters [65]. The canoe was donated to the museum in 1975. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis (August 2023).

Colonization and the Shubenacadie Residential School

The British and French colonized Mi’kma’ki under the Catholic Church’s 15th century Doctrine of Discovery and the concept of Terra Nullius [68][69]. It wasn’t until March of 2023 that the Catholic Church officially denounced the Doctrine of Discovery with an official statement published by the Vatican [70].

It was a combination of factors initiated throughout the nineteenth century that resulted in the oppression of Mi’kmaq peoples in Nova Scotia. In 1821, the reserve system was created in Nova Scotia through colonial “orders-in-council” [71]. In 1857, the Gradual Civilization Act was created as a tool to promote assimilation of Indigenous peoples [72]. The Constitution Act, a facet of confederation in 1867, assigned the Canadian government legal authority over Indigenous peoples and their lands [73]. Following this, the 1869 Gradual Enfranchisement Act took reserve control away from Indigenous peoples and gave it to the Canadian Government [74]. This Act was a significant move in the attempted eradication of Indigenous governance structures. Less than a decade later, the 1876 Indian Act was created [75]. The Indian Act was designed to assimilate Indigenous peoples, which included the creation of Indian Residential Schools. “Indian Agents,” who were assigned to enforce assimilation as well as school attendance, worked for the Department of Indian Affairs [76]. Each of these systems and acts are part of the systemic eradication of Indigenous peoples, and as such, Indigenous peoples have been fighting for recognition that Settler colonialism is genocide.

Settler Colonial Genocide

Image of the Shubenacadie Residential School sourced from the Nova Scotia Museum. Photo taken by Elsie Charles, a survivor of the school who attended in the 1930s [87].

MMIWG2S

MMIWG2S stands for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people. In response to the overrepresentation of Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit peoples in missing and murdered cases [98], a national activist movement arose to draw attention to the epidemic. Unfortunately, due to a variety of factors, statistics on MMIWG2S are inconsistent. MMIWG2S is a result of ongoing colonization and subsequent racism and violence. The Canadian Government developed an official National Inquiry and Action Plan [99][100]. To learn more about MMIWG2S, you can read the Final Report from the National Inquiry [101].

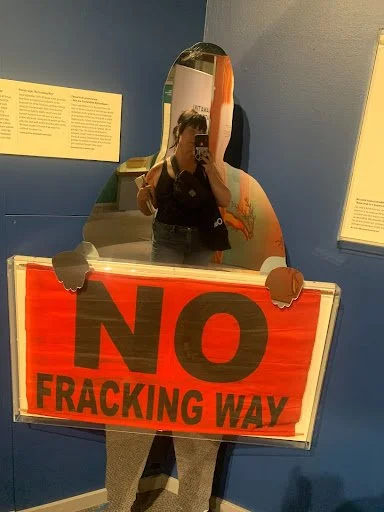

“No fracking way”: Elsipogtog Fracking Protest

In June 2013, the Mi’kmaq people of Elsipogtog First Nation gathered on Highway 11 to protest fracking in the area [102]. The company that intended to frack was a Texas-based corporation [103]. The peaceful protest was met by police carrying assault weapons, pepper spray, and sock rounds [104]. The Mi’kmaq fought back to protect their lands. Forty land warriors were arrested, and six police cars lit on fire [105].

Other recent examples of the fight for sovereignty and Treaty Rights include the Boat Harbor Lawsuit - Pictou Landing Pulp Mill [106][107] and the 2020 Lobster Dispute [108]. To read more about the Mi’kmaq peoples and their/our fight for land rights, we recommend KWILMU’KW MAW-KLUSUAQN: We Are Seeking Consensus.

Photo of an advertisement for a Mi’kmaw-made hockey stick taken at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic by Krista Collier-Jarvis (August 2023).

-

Section 4 “Colonization and the Shubenacadie Residential School“ contains discussion of residential schools and the murder of children.

Section 5 “Contemporary Issues” discusses Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

Seven Districts of Mi’kma’ki. Image from Native Land [10].

Mi’kmaq peoples have a vibrant culture, characterized by art, music, stories, spirituality, and language. On July 17, 2022, Nova Scotia officially recognized Mi’kmaw as the first language of the province.

To learn more about the First Peoples of Mi’kma’ki [17], we recommend Daniel Paul’s book We Were Not the Savages [18], or a visit to the Mi’kmaq Native Friendship Centre [19].

Netukulimk

The Mi’kmaq deeply value the land and their relationships with it. One of their guiding principles is referred to in Mi’kmaq as Netukulimk. Netukulimk is a concept of sustainability that, as the Ta’n a’sikatikl sipu’l | Confluence exhibit at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia states it [21], “describes the use of natural bounty of land for self-sustainment, and the responsibility of maintaining the balance, well-being and mutual respect between people, plants, animals, and the environment” [22]. For more information on Netukulimk, we recommend visiting the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia [23], the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History [24], or the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic [25].

Eight-pointed Star

Each point on the eight-pointed star signifies one of the eight districts of Mi’kma’ki, and the star represents the sun [30]. The earliest recording of it was discovered in 1983 in a rock petroglyph in the Bedford Barrens [31] by a man who was hiking [32]. It is estimated that this petroglyph is at least 500 years old but could very well also have existed prior to colonial contact [33]. The symbol may have been used in Mi’kmaq ceremonies [34], and some researchers speculate that the star petroglyph could be a solar clock/sundial [35].

The star, in other more modern depictions, is often shown in the four traditional colors: red, white, black, and yellow and associated with the medicine wheel [36].

Image from Mi'kmaw Spirit (2016).

The medicine wheel looks at health holistically, taking into consideration four components: mental health, physical health, spiritual health, and emotional health [41]. In each representation of the medicine wheel, however, the goal is to find balance.

Grand Council Flag of Mi’kmaq Nation

The Grand Council Flag of the Mi’kmaq nation is white with a red cross, a red sun (shaped like a star), and red crescent moon [43]. The Wapek (white) background represents “the purity of Creation,” the Mekwek Klujjewey (red cross) represents “mankind and infinity - four directions,” the Nakuset (red sun) represents “forces of the day,” and the Tepkunaset (red moon) represents the “forces of the night” [44].

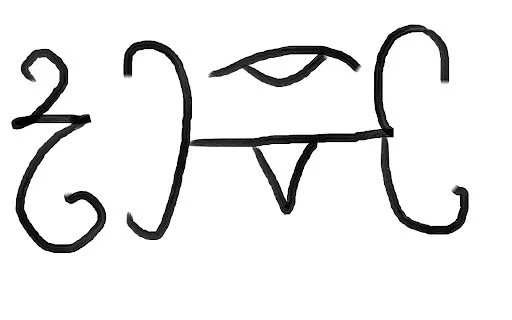

Mi’kmaq Petroglyphs / Suckerfish Writings

Early Mi’kmaq writing has been found in the form of stone petroglyphs [45]. These hieroglyphic writings are called komqwejwi’kasikl, which means “suckerfish writings” [46]. Mi’kmaq oral history reports that suckerfish writings were used prior to colonization [47]. It is difficult to find a thorough recording of suckerfish writings/symbols outside of the context of the Catholic church as the church appropriated suckerfish to deliver prayers and Biblical stories to Mi’kmaq peoples [48]. L’nu artist and writer Michelle Sylliboy published KiskaJeyi – I am Ready in 2019, a book of poetry with traditional komqwejwi’kasikl suckerfish writing [49]. They refer to the term Nmu’ltes, which “represents an ongoing dialogue between two or more people” [50]. Sylliboy writes that “for me, Nmu’ltes expresses a better understanding of the collective consciousness that has motivated me to keep learning and to decolonize and reclaim my Indigenous voice” [51].

Nenuite’tm / I respect

Elasumul / I honor you

**Suckerfish images were drawn on Microsoft Paint by Madeline Rae. Rae copied petroglyph records from the book Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script. The petroglyphs were taken out of the prayer context they were used in in this book. Each petroglyph has a stand-alone meaning as well [52].

Mi’kmaq Cultural Materials

The Mi’kmaq are known as the Quill people, but they also work extensively with baskets, sweetgrass, birchbark, animal skins, and quilting.

Basket weaving

Basket weaving is a traditional practice for the Mi’kmaq peoples, who use all natural plant and animal fibers and dyes in the process [53]. Some of these fibers come from cattail plants, rushes, sweetgrass, American beach grass, moosehair, and moose tendons [54]. Baskets were generally decorated with one of three popular patterns: jikiji’j or periwinkle or curls, porcupine quill, and the diamond [55]. In the seventeenth century, the increase of European industry resulted in a shift from natural dyes to chemical dyes until eventually, basketry went into decline in favour of loom-woven items, such as blankets [56]. For more information on Mi’kmaq basketry, visit Sandra’s website, the Wisqoq archives, or the Kesite’tasikl: Honoring Ancestors Through Collections currently on display at the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History.

Content warning: while Kesite’tasikl contains a wonderful display of Mik’maq cultural materials, there are also three colonial artworks on display that are not critically contextualized. These images use terms such as “squaw” and “savages,” and these can be triggering for some visitors.

Quillwork

The Mi’kmaq are known as the quill people. Quillwork is a technique passed down from Mi’kmaq elders. Today, many quill artists collect porcupine quills from the bodies of roadkill to avoid harming live animals [57]. Cheryl Simon believes “we can honour the porcupine by making something beautiful with its quills” [58]. The quills are then dyed and woven into a variety of materials, such as birchbark to adorn the tops of baskets, or smoked moosehide. According to Simon, “it’s the epitome of being Mi’kmaq when I’m doing my quillwork.” To learn more about the practice and cultural significance of Mi’kmaq quillwork [59], we recommend listening to the Epekwitk Quill Sisters podcast [60].

Drum Making

The drum is a sacred object to the Mi’kmaq peoples [61]. Drums are traditionally made from wood and animal skins, and they are sometimes blessed in ceremony prior to use [62]. Mi’kmaq artist, Alan Syllaboy, is known for his Daily Drum series [63], where he combines drum making, art, and shares daily traditional teachings. To hear what the drum sounds like, we recommend listening to the Mi’kmaq Honour Song [64].

Birchbark Canoes

Mi’kmaq canoes were typically crafted from the heavy bark of the white birch tree [66]. Unlike other birchbark canoes constructed in what we currently call Canada, Mi’kmaq canoes were shaped slightly differently and were constructed in the reverse order [67].

“… genocide is a gradual process and may begin with political disenfranchisement, economic displacement, cultural undermining and control, the destruction of leadership, the break-up of families and the prevention of propagation. Each of these methods is a more or less effective means of destroying a group. Actual physical destruction is the last and most effective phase of genocide. ”

In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper, issued a residential school apology on behalf of the Government of Canada, but he did not use the word “genocide” [78] nor did Pope Francis in his apology on behalf of the Catholic Church’s involvement in Residential Schools [79], nor did the Sisters of Charity in their apology for their involvement in the Shubenacadie Residential School [80].

Residential Schools

Residential Schools were government sponsored, church run institutions designed to assimilate Indigenous children. Approximately 130 Schools operated across Canada between 1831-1996 with over 150,000 children passing through their doors. Conditions in the Schools were despicable: they were overcrowded with poor sanitation, no medical care, inadequate heating, and were run by people who generally saw Indigenous children as “savages.” As such, the children suffered malnourishment, physical abuse, sexual abuse, sickness, and death.

In 2021, 215 unmarked graves were discovered at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in B.C., sparking renewed attention toward the sad history of the Schools, prompting the search of other locations, and verifying the statements made by Indigenous parents and communities who claimed that they knew but were ignored all these years.

“For many Canadians and for people around the world, these recent recoveries of our children — buried nameless, unmarked, lost and without ceremony are shocking, and unbelievable. Not for us, we’ve always known.”

RoseAnne Archibald, the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations

Not all locations have yet been searched.

Shubenacadie Residential School (1929-1967)

The Shubenacadie Residential School was the only residential school that operated in the Maritimes. It was built on the land of the Sipekne'katik First Nation of Mi’kma’ki near Shubenacadie [84][85]. 10% of Mi’kmaq children lived at the “school,” and during its 37 years, it is estimated that over 1,000 Mi’kmaq children attended [86].

The staff at the Shubenacadie Residential School consisted of members from the Roman Catholic Church. Father Jeremiah Mackey was the school’s headmaster from 1928-1958 [88], and the rest of the staff were nuns from the Sisters of Charity. The Sisters of Charity [89] are also the founders of Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU) [90], and in 2021, MSVU officially apologized for the role the Sisters of Charity played in the Shubenacadie Residential School; MSVU also issued a series of “commitments” in consultation with Indigenous Elders and the L’nu Advisory Circle [91].

Shubenacadie Residential School was named after the Shubenacadie River that ran alongside it. When Elder Dorene Bernard attended the School as a child, she would look out a school window and gaze at the river below as a symbol of freedom [92]. In Spring of 2021, Bernard guided investigations into the Shubenacadie grounds [93], which were in response to the hundreds of unmarked graves of children discovered at other Residential School locations across Canada. Although unmarked graves were not discovered at this location, there is a list of children who passed away while attending the school [94].

The Shubenacadie School closed in 1967 primarily due to its lack of resources [95]. The Shubenacadie school was severely overcrowded and under-resourced, adding to the discomfort and harm towards the Indigenous children who were forced to attend. The building was demolished in 1986, and a plastic factory sits in its place. The land is considered a historic site [96]. To learn more about the Shubenacadie Residential School, we recommend a visit to the former site as well as Isabelle Knockwood’s memoir: Out of the depths: The experiences of Mi’kmaw children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia [97].

Contemporary Issues

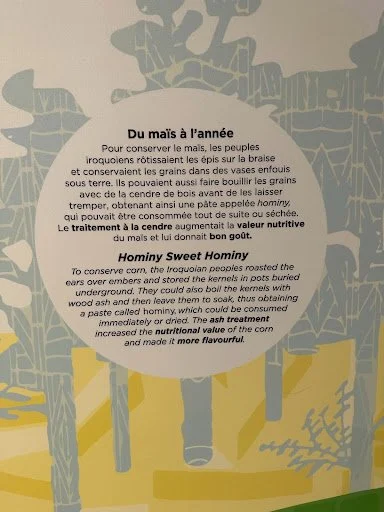

Representation in Museums

The sole reliance on past tense language suggests that Indigenous peoples only exist in the “past.” While some use of past tense is acceptable owing to some practices no longer being used by Indigenous communities, unfortunately, many institutions, including museums, rely solely on past tense language in their present day exhibitions. Additionally, describing Indigenous peoples and traditions as “they” suggests that Indigenous peoples are not potential visitors, but are instead excluded from museum spaces. This language can be problematic and misleading and contribute to ongoing colonization.

A placard on display at the temporary exhibition, Indigenous Ingenuity, at the Discovery Centre describing how the Iroquois stored their corn. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis (2023).

An anti-fracking poster “No Fracking Way” held by a person-shaped mirror on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Photo by Madeline Rae (August 2023).

A Contribution to the Game of Hockey

Early hockey sticks were carved from the wood of the Hornbeam trees, which are native to NS, using a “crooked knife” [111]. Archival photographs reveal that the Mi’kmaq were some of the first peoples to carve these sticks and trade them with colonizers [112]. Unfortunately, the high demand for hockey sticks resulted in the depletion of the Hornbeam trees, so later hockey sticks were carved from the wood of the Yellow birch tree [113].

To learn more about the First Peoples of Mi’kma’ki, we recommend a visit to the Art Gallery of NS, the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, or the NS Museum of Natural History. You can also check out the Mi’kmaq Portraits Gallery online from the Nova Scotia Museum.

October is Mi’kmaq History Month

Mi’kmaq History Month takes place annually in October and begins with Treaty Day on October 1st [109]. During Mi’kmaq History Month, we celebrate the history and culture of Mi’kmaq people. The 2023 theme is Mi’kmaw Traditional Games and Sports. The theme is fitting, given that Mi’kma’ki hosted the 2023 North American Indigenous Games [110].

References

(see here for full bibliography)

[1] Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission, “National Indigenous History Month,” Province of Nova Scotia, June 8, 2022, accessed September 7, 2023, https://humanrights.novascotia.ca/news-events/news/2022/national-indigenous-history-month

[2] Sarah Isabel Wallace, “Peace and Friendship Treaties”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, Government of Canada, May 30 2018, August 11 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/peace-and-friendship-treaties.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Heather Conn, “Sylliboy Case”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, Government of Canada, April 5 2018, August 11 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sylliboy-case.

[5] Heather Conn, “Marshall Case”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, Government of Canada, April 11 2020, August 11 2023, https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/marshall-case.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] L’nuey, “Treaties of Peace and Friendship,”, L’nuey: Moving Toward a Better Tomorrow, accessed September 7, 2023, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://lnuey.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/lnuey_4291_treatyday_ResearchPaper_V01_lowres.pdf.

[10] “Mi’kma’ki Territories”, Native Land Digital, December 9 2022, August 11 2023, https://native-land.ca/maps/territories/mikmaq/.

[11] “Office of L’nu Affairs: About Us”, Government of Nova Scotia, August 11 2023, https://beta.novascotia.ca/government/lnu-affairs/about.

[12] L’Nu’k: The People: Mi’kmaw History, Culture, and Heritage”, Millbrook Cultural & Heritage Centre”, August 14, 2023, https://www.millbrookheritagecentre.ca/product-page/l-nu-k-the-people-mi-kmaw-history-culture-and-heritage-1.

[13] “Msit No’kmaq: All my relations” Exhibit, Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, July 24 2023, https://naturalhistory.novascotia.ca/.

[14] “Kesite’tasikl: Honoring Ancestors Through Collections”, (Exhibition, Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, July 24 2023).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Vernon Ramesar, “Mi’kmaw officially recognized as Nova Scotia’s original language at Sunday ceremony,” CBC Nova Scotia, CBC/Radio-Canada, July 17, 2022, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/mi-kmaw-officially-recognized-nova-scotia-first-language-1.6523359.

[17] Daniel N. Paul, “Mi’kmaq Culture,” Daniel N. Paul, accessed September 7, 2023, http://www.danielnpaul.com/Mi%27kmaqCulture.html.

[18] Daniel N. Paul, We Were Not The Savages (Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2000).

[19] Mi’kmaw Native Friendship Centre (MNFC), “Wije’winen,” MNFC, accessed September 7, 2023, https://wijewinen.ca/.

[20] Daniel N. Paul, First Nations History: We Were Not the Savages: Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations (Fernwood Publishing, 2022).

[21] Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, “Ta’n a’sikatikl sipu’l/Confluence,” Art Gallery NS, https://agns.ca/exhibition/tan-asikatikl-sipul-confluence/.

[22] “Sustainability and Treaty,” Ta’n a’sikatikl sipu’l|Confluence, Art Gallery NS.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Museum of Natural History, “Netukulimk,” Museum of Natural History, Nova Scotia Department of Communities, Culture, Tourism, and Heritage, accessed September 7, 2023, https://naturalhistory.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/permanent-exhibits/netukulimk.

[25] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Ta’n me’j Tel-keknuo’ltiek/How Unique We Still Are,” Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Nova Scotia Department of Communities, Culture, Tourism, and Heritage, accessed September 7, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/tan-mej-tel-keknuoltiek.

[26] “The Seven Teachings,” Southern First Nations Network of Care, August 11 2023, https://www.southernnetwork.org/site/seven-teachings.

[27] Edward Benton-Banai, The Mishomis book: the voice of the Ojibway (Minneapolis, Minnesota Press, 2010).

[28] Trevor Sanipass & CBC, “They’re so interconnected’: The Significance of the 7 sacred teachings”, CBC News, Nova Scotia, Feb 19 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/seven-sacred-teachings-mi-kmaq-column-trevor-sanipass-eagle-kitpu-love-1.5467321.

[29] “Ta’n Me’j Tel-Keknuo’ltiek: How Unique We Still Are” (Exhibition, Nova Scotia Atlantic Maritime Museum, August 2023).

[30] “Mide-Wiigwas: Eight Pointed Star”, Penwaaq L nu k, Benoit First Nation, 2005, https://www.benoitfirstnation.ca/eight_pointed_star.html.

[31] “Bedford Barrens Petroglyph”, Trailpeak, https://trailpeak.com/trails/bedford-barrens-pteroglyphs-near-halifax-ns-12269.

[32] “The Migmaq Star”, Speaking Out About Our Land: Nm’Tginen, Canadian Heritage, 2009-2023, http://www.aboutourland.ca/resources/migmaq-stories/migmaq-star-0.

[33] “Mide-Wiigwas: Eight Pointed Star”, Penwaaq L nu k, Benoit First Nation, 2005, https://www.benoitfirstnation.ca/eight_pointed_star.html.

[34] “Bedford Petroglyphs National Historic Site of Canada”, Parks Canada, Directory of Federal Heritage Designations, Canada.ca, https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=827.

[35] “A Solar Clock?”, Cboze Research Site - Bedford Barrens 8-Pointed Star, Accessed August 11, 2023, https://cbozeresearch.blog/about/#:~:text=What%20is%20known%20as%20the%20Mi%E2%80%99kmaq%20Eight%20Point,any%20other%20known%20petroglyph%20site%20in%20Atlantic%20Canada.

[36] “Mide-Wiigwas: Eight Pointed Star”, Penwaaq L nu k, Benoit First Nation, 2005, https://www.benoitfirstnation.ca/eight_pointed_star.html .

[37] Mikmaw Spirit, “Mi’kmaw Culture,” muiniskw.org, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.muiniskw.org/pgCulture2b.htm.

[38] The Preservation Project, “What is the Medicine Wheel? Teachings by Jeff Ward,” Youtube, July 15 2019, Video, 4:48,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSw0s8rcuSg.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] “Mi’kmaq/Lun’k Grand Council Flag”, Benoit First Nation, 2005, August 11 2023, https://www.benoitfirstnation.ca/grandCouncil_flag_symbolism.html.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] David Schmidt, Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script (Halfiax, Canada, Nimbus Publishing, 2006).

[46] Michell Sylliboy, Kiskajeyi: I am Ready (Nanoose Bay, BC, Canada, Rebel Mountain Press, 2019), 8.

[47] Ibid.

[48] David Schmidt, Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script (Halfiax, Canada, Nimbus Publishing, 2006).

[49] Michell Sylliboy, Kiskajeyi: I am Ready (Nanoose Bay, BC, Canada, Rebel Mountain Press, 2019).

[50] Michell Sylliboy, Kiskajeyi: I am Ready (Nanoose Bay, BC, Canada, Rebel Mountain Press, 2019), 8.

[51] Ibid.

[52] David Schmidt, Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script (Halfiax, Canada, Nimbus Publishing, 2006).

[53] Gordon, Joleen. “Tradition and Adaptation: The Evolution of Mi’kmaq Basketry,” Ornamentum, 2011, accessed September 3, 2023, https://www.ornamentum.ca/post/tradition-and-adaptation-the-evolution-of-mi-kmaq-basketry.

[54] ibid.

[55] ibid.

[56] ibid.

[57] Gallant, Isabelle. “Mi’kmaq Quillwork Podcast Delves into Issues of Indigenous Identity,” CBC, October 9, 2021, accessed September 3, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/prince-edward-island/pei-mi-kmaw-quillwork-podcast-1.6190744.

[58] ibid.

[59] ibid.

[60] Cheryl and Kay, Epekwitk Quill Sisters, podcast, https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/epekwitk-quill-sisters/id1567885864.

[61] Mawkina’masultinej: Pepkwejete’maqn (Drum) Inquiring Into The Drum,” Show Me Your Math, accessed September 3, 2023, https://showmeyourmath.ca/mawkinamasultinej-lets-learn-together/mawkinamasultinej-pepkwejetemaqn-drum/.

[62] ibid.

[63] Alan Syliboy, “Drum Series,” Redcrane Studios, accessed September 7, 2023, https://alansyliboy.ca/drum-series/.

[64] Nova Scotia Community College, “Mi’kmaw Honour Song - Mi’kmaq Sign Language,” Youtube, June 23, 2022, video, 7:54, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGAIhr81ymc.

[65] Nsarchives, “Porpoise Oil (1936, Pt. 1 of 2),” Youtube, September 2, 2010, video, 12:43, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wOlWJSFRw7w.

[66] Gordon, Joleen. “Tradition and Adaptation: The Evolution of Mi’kmaq Basketry,” Ornamentum, 2011, accessed September 3, 2023, https://www.ornamentum.ca/post/tradition-and-adaptation-the-evolution-of-mi-kmaq-basketry.

[67] “Mi'kmaq Birchbark Canoes,” Avon River Heritage Society, accessed September 3, 2023, http://www.avonriverheritage.com/mikmaq-birch-bark-canoes.html.

[68] Travis Tomchuk, “The Doctrine of Discovery: A 500-year-old colonial idea that still affects Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples”, Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Government of Canada, November 2, 2022, August 11, 2023, https://humanrights.ca/story/doctrine-discovery.

[69] Wikipedia, “Terra Nullius”, August 8, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_nullius.

[70] Vatican, “Joint Statement of the Dicasteries for Culture and Education and for Promoting Integral Human Development on the “Doctrine of Discovery”, 30.03.2023”, Holy See Press Office, March 30, 2023, August 11, 2023, https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2023/03/30/230330b.html/

[71] “This is What I Wish You Knew”, (Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, Halifax July 24, 2023).

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Facing History & Ourselves, “Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention,” Facing History, May 12, 2020, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/raphael-lemkin-genocide-convention.

[78] Stephen Harper “Statement of apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools”, Government of Canada, June 11, 2008, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100015644/1571589171655.

[79] The Canadian Press (quoting Pope Francis) “‘I am deeply sorry’: Full text of residential school apology from Pope Francis”, CBC News, July 25, 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/pope-francis-maskwacis-apology-full-text-1.6531341.

[80] Mount Saint Vincent University, “MSVU apologizes for its role in the tragedy of residential schools in Canada, shares commitment to Indigenous People,” Mount Saint Vincent University, October 20, 2021, https://www.msvu.ca/msvu-apologizes-for-its-role-in-the-tragedy-of-residential-schools-in-canada-shares-commitments-to-indigenous-peoples/.

[81] “History of Residential Schools,” Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, accessed September 7, 2023, https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/history-of-residential-schools/.

[82] Dickson, Courtney, and Bridgette Watson, “Remains of 215 Children Found at Buried at Former B.C. Residential School, First Nation Says,” CBC, May 28, 2021, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/tk-eml%C3%BAps-te-secw%C3%A9pemc-215-children-former-kamloops-indian-residential-school-1.6043778.

[83] Austen, Ian, “How Thousands of Indigenous Children Vanished in Canada,” The New York Times, March 28, 2022, accessed September 10, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/07/world/canada/mass-graves-residential-schools.html.

[84] Sipekne’katik, “A Mi’kmaq community rooted in the traditions and history of our ancestors,” Sipekne’katik 1752, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.sipeknekatik.ca/.

[85] “This is What I Wish You Knew”, (Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, Halifax July 24, 2023).

[86] Ibid.

[87] Elsie Charles, (untitled), 1930, Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, https://novascotia.ca/museum/mikmaq/?section=image&page=&id=818®ion=&period=&keywords=.

[88] Briar Dawn Ransberry, “”Teach Your Children Well”: Curriculum and Pedagogy at the Shubenacadie School, Nova Scotia, 1951-1967” Master’s Thesis, National Library of Canada, 2000, 2.

[89] Ibid.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Mount Saint Vincent University, “MSVU apologizes for its role in the tragedy of residential schools in Canada, shares commitment to Indigenous People”, Mount Saint Vincent University, October 20, 2021, https://www.msvu.ca/msvu-apologizes-for-its-role-in-the-tragedy-of-residential-schools-in-canada-shares-commitments-to-indigenous-peoples/.

[92] Dorene Bernard, “This is What I Wish You Knew”, (Video, Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, Halifax July 24, 2023).

[93] Gareth Hampshire, “Former site of Shubenacadie Residential School scanned for human remains”, CBC News, May 31, 2021, August 11, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/shubenacadie-residential-school-kamloops-radar-remains-1.6047347.

[94] “Shubenacadie: St. Anne’s Convent”, National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, University of Manitoba, https://nctr.ca/residential-schools/atlantic/shubenacadie-st-annes-convent/.

[95] Ibid.

[96] “The Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School National Historic Site of Canada, Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia”, Parks Canada, Government of Canada, https://www.canada.ca/en/parks-canada/news/2021/09/the-former-shubenacadie-indian-residential-school-national-historic-site-of-canada-shubenacadie-nova-scotia.html.

[97] Isabelle Knockwood Out of the depths: The experiences of Mi’kmaw children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, Fernwood Publishing, 2015.

[98] Government of Canada, “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls: Research and Statistics Division,” Government of Canada, January 20, 2023, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/jf-pf/2017/july04.html#:~:text=The%20rate%20of%20murdered%20Indigenous%20women%20in%20Canada%20was%204.82%20per%20100%2C000.&text=The%20rate%20of%20murdered%20Indigenous%20women%20in%20Manitoba%20was%207.16,was%206.79%3B%20Saskatchewan%20was%206.01.&text=Footnote%207-,Due%20to%20the%20small%20numbers%2C%20comparing,should%20be%20done%20with%20caution.

[99] Government of Canada, “National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls,” Government of Canada, September 9, 2022, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1448633299414/1534526479029.

[100] Mmiqg2splus-nationalactionplan, “National Action Plan,” accessed September 7, 2023, https://mmiwg2splus-nationalactionplan.ca/eng/1670511213459/1670511226843.

[101] National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, “Final Report,” accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/.

[102] The Outpost, “Fracking New Brunswick: Elsipogtog First Nation Takes a Stand”, WilderUtopia: Coexisting Into the Great Unknown, December 7, 2013, August 11, 2023, https://wilderutopia.com/environment/energy/fracking-new-brunswick-elsipogtog-first-nation-takes-stand/.

[103] ibid.

[104] ibid.

[105] ibid.

[106] Joan Baxter, “For 50+ years, pulp mill waste has contaminated Pictou Landing First Nation’s land in Nova Scotia,” CBC News, CBC/Radio-Canada, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/cbcdocspov/features/for-50-years-pulp-mill-waste-has-contaminated-pictou-landing-first-nations.

[107] Michael Gorman, “Northern Pulp files lawsuit against N.S. for damages, lost profits,” CBC Nova Scotia, CBC/Radio-Canada, December 17, 2021, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/northern-pulp-boat-harbour-law-suit-court-1.6289979#:~:text=Northern%20Pulp%20alleges%20the%20creation%20of%20the%20act%2C,Nation%20%E2%80%94%20the%20community%20that%20neighbours%20Boat%20Harbour..

[108] Laura Hensley, “The Attacks on Mi’kmaq Lobster Fishers in Nova Scotia, Explained,” Refinery29, October 23, 2020, accessed September 7, 2023, https://www.refinery29.com/en-ca/2020/10/10111352/nova-scotia-lobster-dispute-explained.

[109] “Mi’kmaw Traditional Games & Sports”, Mi’kmaq Wikewiku’s History Month, August 11, 2023, https://mikmaqhistorymonth.ca/.

[110] North American Indigenous Games, “About,” Government of Canada, Government of Nova Scotia, Halifax Regional Municipality, accessed September 7, 2023, https://naig2023.com/about/.

[111] “Micmac Hockey Sticks”, The Birthplace of Hockey, August 11, 2023, https://birthplaceofhockey.com/hockey-history/origin/micmac-hockey-sticks/.

[112] ibid.

[113] ibid.

AFRICVILLE

“Where the pavement ended, Africville began”

Africville (“a spirit that lives on”)[3] is a rich part of the culture of Nova Scotia. Africville refers to an area and a community of people. The area of Africville is located around the south end of the Bedford Basin, now locatable by the aptly named “Africville Road” running east off Barrington Street. Although the Africville community existed as early as the 1700s, the first documented land purchase was in 1848 [4]. For more information on the timeline of Africville, we recommend a visit to the Africville Museum [5].

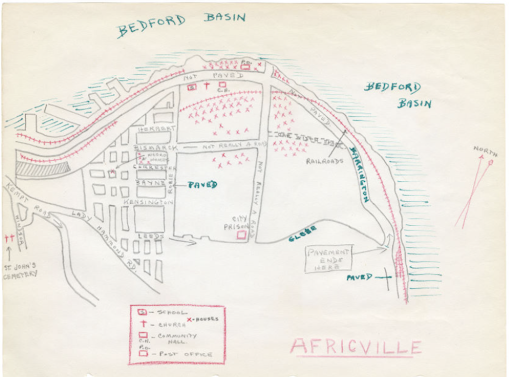

Sketch map of Africville. Image from the Nova Scotia Archives (1949) [2].

Image of a family in their living room in Africville. Image from Nova Scotia Archives (1965) [6].

Despite the destruction of the physical homes and businesses in Africville, the community lives on. The Africville Genealogy Society hosts the annual Africville reunion weekend [12][13]. In 2010, decades after the people of Africville were displaced, Halifax Regional Municipality officially apologized [14]. Community members of Africville are still seeking proper reparations for their forced relocation and the destruction of their homes [15].

The Church

The church has always been a central tenet of the Africville community [16], and the Africville Museum is today located inside the Seaview United Baptist Church on Africville Road. The Baptist denomination was brought to the region by David George in 1782, and in 1854 Reverend Richard Preston organized a conference which resulted in the creation of the African United Baptist Association [17][18]. In 1874, one of the biggest group baptisms of all time took place in the Bedford Basin by Reverend James Thomas [19]. The church has been, and remains, a significant part of the culture of Africville. Images of community gatherings at the church can be seen on the Nova Scotia Archives website [20].

Culture

Africville has a rich culture that continues to live on.

There have been many books written about the story of Africville, both fiction and non-fiction, including a cookbook of Africville recipes (2020) [22], The Spirit of Africville by the Africville Genealogy Society and contributors (1992)[23], A Love Letter to Africville by Amanda Carvery-Taylor (2021)[24], Big Town: A Novel of Africville by Stephens Gerard Malone (2011)[25], Last Days in Africville by Dorothy Perkins (2006)[26], Africville my home by Leslie Carvery (2016)[27], Africville by Jeffery Colvin (2019)[28], and Africville by Shauntay Grant (2018)[29].

In 1991, Shelagh Mackenzie made Remembering Africville, a film that can be accessed for free online [30]. Other films that document Africville include Africville: Look Back (2016)[31], Africville: The Black community bulldozed by the city of Halifax (2020)[32], History Bits: Remembering Africville (2022)[33], and CTV’s Reflecting on the Legacy of Africville (2017)[34].

Africville was home to many athletes. For example, some members from Africville played on the Rangers baseball team [36].

A mural of boxer George Dixon located next to the Africville Museum. Image taken by Madeline Rae (August 15th 2023). Mural created by Michael Burt and assisting artists [37]. Michael Burt owns Trackside Studios [38], an organization of local artists.

Image of Africville hockey team “Africville Seasides” from the Nova Scotia Archives (specifically Tom Connors Nova Scotia Archives 1987-218 number 133/ negative N-1726), (1922).

Forced Relocation

After the Nova Scotian government built several hazardous and unsafe industries in the area, 400 families were forcibly relocated between 1964 and 1967 [7]. This displacement was called the “Africville issue” in local papers [8]. On January 2, 1970, the last resident of Africville, Aaron “Pa” Carvery, left his home [9]. To read more about the effects of the displacement on one resident, Eddie Carvery, we recommend The Hermit of Africville [10].

Despite the Nova Scotian government’s devastation of the land of Africville and the relocation of the community, Africville continued to live in its people, in its stories, and its culture [11].

Cropped image of the back of Seaview African United Baptist Church facing the Bedford Basin, 1965. Image sourced from Nova Scotia Archives Website [21].

Image of a community baseball game in Africville from the Nova Scotia Archives (July, 1949).

“Pioneering” boxer George Dixon is perhaps the most well-known athlete from the community [39]. A plaque sharing Dixon’s story is placed directly outside the Africville Museum, adjacent to a large mural of him in action. There is also a community center in Halifax named after George Dixon, called the George Dixon Community Centre, located at 2501 Gottingen Street/2502 Brunswick Street [40].

Hockey was also a prevalent sport practiced in the community; the two teams were the Africville Brown Bombers and the Africville SeaSides [41][42]. Both teams were part of the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes [43].

For more information, we recommend a visit to Africville to see the museum and engage in a Walking Tour through the area that was once a thriving Black cultural center and home to hundreds of families.

References

(see here for full bibliography)

[1] Remembering Africville, directed by Shelagh Mackenzie (1991), https://search.alexanderstreet.com/preview/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C3800360

[2] Nova Scotia Archives Library Brookbank, Sketch map of Africville, sketch on paper, 1949, Nova Scotia Archives, https://archives.novascotia.ca/african-heritage/archives/?ID=666.

[3] Welcome to the Africville Museum,” Africville Museum, Africville Heritage Trust, Accessed August 21, 2023, https://africvillemuseum.org/.

[4] Africville Museum, “Africville” (Exhibition, Africville Heritage Trust, 5795 Africville Rd., Halifax, NS, August 15th 2023).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Bob Brooks, Family in their living room, Africville, 1965, black and white negative contact print, Nova Scotia Archives/Gone but Never Forgotten/Bob Brooks Nova Scotia Archives 1989-468 vol. 16 negative sheet 1 image 11, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africville/archives/?ID=40.

[7] “Africville Timeline,” Africville Museum, Africville Heritage Trust, Accessed August 21, 2023, https://africvillemuseum.org/africville-heritage-trust/africville-timeline/.

[8] Mail Star, Expert To Seek Solution For Africville Issue, Mail Start excerpt, September 13, 1963, Scanned newspaper clipping, Africville Nova Scotia Archives MG 100 volume 100 number 44 AJ, https://archives.novascotia.ca/african-heritage/archives/?ID=615.

[9] “Africville: Recognizing the Past, Present, and Future,” Halifax, accessed September 3, 2023, https://www.halifax.ca/about-halifax/diversity-inclusion/african-nova-scotian-affairs/africville#:~:text=The%20last%20Africville%20resident%20%2D%20Aaron,spiritual%20heart%20of%20their%20community.

[10] Jon Tattrie, The Hermit of Africville: The Life of Eddie Carvery (East Lawrencetown, NS: Pottersfield Press, 2010).

[11] Historica Canada, “Africville: The Black community bulldozed by the city of Halifax,” Youtube, February 12, 2020, Video, 2:02, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SwNa0H4s0s.

[12] Africville Genealogy Society, “Africville Genealogy Society,” Facebook, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/africville/.

[13] Britnei Bilhete, “Africville 40th reunion marks long-awaited homecoming for former residents, descendants,” CBC Nova Scotia, CBC Radio-Canada, July 21, 2023, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/africville-40th-reunion-marks-long-awaited-homecoming-for-former-residents-descendants-1.6913700.

[14] Halifax Municipal Government, “Apology: An Apology for Africville,” Halifax, Halifax Municipal Government, 2010, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.halifax.ca/about-halifax/diversity-inclusion/african-nova-scotian-affairs/africville/apology.

[15] Allan April, Nick Moore, “‘Rally for reparations’ held by descendants of Africville, 50 years after demolition,” CTV News Atlantic, Bell Media, October 24, 2020, accessed September 5, 2023, https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/rally-for-reparations-held-by-descendants-of-africville-residents-50-years-after-demolition-1.5159463.

[16] “Timeline,” Africville, Accessed August 21, 2023, http://africville.ca/timeline/.

[17] Africville Museum, (Exhibition, Africville Heritage Trust, 5795 Africville Rd., Halifax, NS, August 15th 2023).

[18] African United Baptist Association of Nova Scotia, “Home,” AUBA, accessed September 5, 2023, http://www.aubans.ca/web/.

[19] Africville Museum, (Exhibition, Africville Heritage Trust, 5795 Africville Rd., Halifax, NS, August 15th 2023).

[20] Bob Brooks, View overlooking the back of Seaview African United Baptist Church, Africville, 1965, black and white negative contact print, Nova Scotia Archives/Gone but Never Forgotten/Bob Brooks Nova Scotia Archives 1989-468 vol. 16/ negative sheet 4 image 19,, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africville/archives/?ID=8.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Adina Fraser-Marsman, Juanita Peters, Claudia Castello-Prentt, In the Africville Kitchen: The Comforts of Home (Halifax, NS: Africville Heritage Trust, 2020).

[23] Africville Genealogy Society, Donald Clairmont, Stephen Kimber, Bridglal Pachai, Charles Saunders, The Spirit of Africville (Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1992).

[24] Amanda Carvery-Taylor, A Love Letter to Africville (Fernwood Publishing, 2021).

[25] Stephens Gerard Malone, Big Town: A Novel of Africville (Halifax: Nimbus, 2011).

[26] Dorothy Perkins, Last Days in Africville (Vancouver: Beach Home Publishing, 2003).

[27] Leslie Carvery, Africville my home (Halifax: Leslie Carvery, 2016).

[28] Jeffery Colvin, Africville (Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2019).

[29] Shauntay Grant, Africville (Toronto: Groundwood Books, 2018).

[30] Remembering Africville, directed by Shelagh Mackenzie (1991; Canada), Viewable Online: https://search.alexanderstreet.com/preview/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C3800360.

[31] CBC News: The National, “Africville: Look Back,” Youtube, February 29, 2016, Video, 2:13, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1imr0T5U3Yc.

[32] Historica Canada, “Africville: The Black community bulldozed by the city of Halifax,” Youtube, February 12, 2020, Video, 2:02, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SwNa0H4s0s.

[33] Canada’s History, “History Bits: Remembering Africville / Parcelles d/histoire : Se souvenir d’Africville,” Youtube, January 26, 2022, Video, 5:10, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iTtNtVWTEo8.

[34] CTV Your Morning, “Reflecting on the Legacy of Africville, Your Morning,” Youtube, June 8, 2017, Video, 7:48, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=avA5gHsp9ic.

[35] Nova Scotia Archives, Baseball in Africville, July 1949, black and white photograph, Nova Scotia Archives Library Brookbank 1990-191, https://archives.novascotia.ca/african-heritage/archives/?ID=667.

[36] Africville Museum, (Exhibition, Africville Heritage Trust, 5795 Africville Rd., Halifax, NS, August 15th 2023).

[37] Emma Davie, “Mural of Africville’s George Dixon to mark boxing champion’s 150th birthday,” CBC Nova Scotia, CBC/Radio-Canada, July 20, 2020, accessed September 6, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/george-dixon-boxing-champion-mural-africville-1.5650845#:~:text=Michael%20Burt%20said%20he%20and%20the%20other%20two,area%20and%20bring%20attention%20to%20the%20underrepresented%20community.

[38] Trackside Studios, “About,” Trackside Studios, accessed September 6, 2023, https://www.tracksidestudios.ca/about.

[39] Bally Sports North, “Black History Month: George “Little Chocolate” Dixon was a boxing pioneer,” Youtube, February 14, 2021, Video, 1:52, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zt5kR1fTOz8.

[40] Halifax Municipal Government, “George Dixon Community Centre,” Halifax Municipal Government, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.halifax.ca/parks-recreation/programs-activities/recreation-centres-your-community/george-dixon-community.

[41] Pal Palmeter, “All-black hockey game Colored Hockey League,” CBC Nova Scotia, CBC Radio-Canada, February 4, 2018, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/all-black-hockey-game-to-honour-colored-hockey-league-1.4516748.

[42] Tom Connors, Africville Sea-Sides, c.1922, 1922, Negative, Tom Connors Nova Scotia Archives1987-218 number 133/ negative N-1726, https://archives.novascotia.ca/connors/archives/?ID=125.

[43] George Fosty, Darril Fosty, “Coloured Hockey League,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, September 16, 2022, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/coloured-hockey-league.

[44] Tom Connors, Africville Sea-Sides, c. 1922, 1922, negative contact print, Nova Scotia Archives/Tom Connors Nova Scotia Archives 1987-218 number 133/negative N-1726, https://archives.novascotia.ca/connors/archives/?ID=125.

[45] Danielle Mohan, Paula Grant-Smith, Africville Heritage Trust, Halifax Regional Municipality, Walking Africville Audio Tour, read by Paula Grant-Smith, George Grant Jr., Lyle Grant, Bernice Arsenault, Beatrice Wilkins, Linda Mantley, Brenda Steed-Ross (Halifax: Halifax Regional Municipality: 2022), audio file, 29:37, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/7b456eb7201d45fea813bd0b3914fab4.

HALIFAX EXPLOSION

On December 6th, 1917, at 9:04 am, the largest non-atomic explosion in history took place in Halifax Harbour [1]. Over 1,700 people perished [2], and another 9,000 were injured. The Halifax Explosion Remembrance Book Database offers a complete list of those who lost their lives [3]. A large number of the victim’s identities were not discovered until decades later.

Image of clock from Halifax Explosion frozen at the time of the explosion. The Clock is on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Photo by Madeline Rae (July 2023).

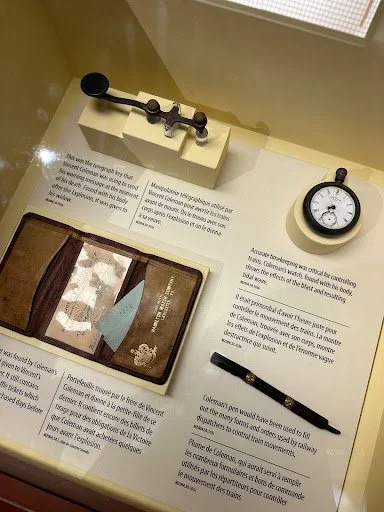

A display case at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic displays several objects belonging to Vincent Coleman. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis (August 2023).

The explosion happened when two ships collided in the foggy harbour [4]. The Mont-Blanc, a ship full of explosives, was entering into the harbour while the Imo was preparing to leave [5]. At 8:45am, the Imo hit the Mont-Blanc, causing a fire. While the Mont-Blanc’s crew abandoned the ship, it came into the pier where it then exploded [6]. This area of the harbour is known as Kepe’kek, which means “at the narrows” in Mi’kmaw [7].

The explosion destroyed entire neighborhoods, wiping out buildings and trees [8]. Schools became morgues and prisons became shelters for the homeless [9]. A map of the affected area can be viewed online here [10]. Real footage from the aftermath and relief efforts can be seen here [11], and an immersive video of the collision and subsequent explosion can be viewed here [12]. (Content warning: video contains visceral experience of explosion and resulting destruction and panic).

One of the most well-known stories of the Halifax Explosion is about Vincent Coleman [13], a train dispatcher, who sacrificed his life to warn an incoming train about the potential explosion [14]. Today, he is heralded as a hero, and his story was featured in one of Canada’s Heritage Minutes [15]. He now lies in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Halifax, N.S. [16].

The Tufts Cove Survivor (2009) is on display just outside the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic and is part of a larger collection permanently on display at the Art Gallery of NS. Photo by Krista Collier-Jarvis (August 2023) [21].

Community Relief

African Nova Scotian Dr. Clement Courtenay Ligoure was one of the first medical professionals to respond [22]. Dr. Ligoure had a private clinic that he named after his mother, called the Amanda Private Hospital, which Dr. Ligoure opened after finding it difficult to get funding for a public hospital [23]. After the explosion, Dr. Ligoure worked for days treating the victims who were turned away from the overflowing hospital [24]. Finally, the military sent in people to help his efforts. Dr. Ligoure saved many lives, and generously charged no one for his medical care [25].

Dr. Ligoure also played a significant role in the formation of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, the largest all-Black Canadian military unit [26].

Image of exhibition entrance at the Atlantic Maritime Museum. Photo by Madeline Rae (July 2023).

Turtle Grove

The Mi’kmaw community Turtle Grove was hit fully by the blast [17], and whatever was not burned in the fire was destroyed by the subsequent tsunami [18]. Half of the residents of Turtle Grove survived, but were displaced to other reserves, and the Mi’kmaw community was the only community that was never rebuilt [19]. William Prosper, who was the last living member of the community, was nicknamed “the Tufts Cove survivor” by artist Alan Syliboy [20].

Image taken at Maritime Museum of the Atlantic by Madeline Rae (August 2023).

Museums and Media

Explosion in the Narrows is a permanent exhibit on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic [27]. It features stories from the survivors as well as the affected communities. It also featured various artifacts such as timepieces, mortuary bags, and their contents.

As part of their exhibition Explosion! Dartmouth’s Ordeal of the 1917 Disaster [28], the Dartmouth Heritage Museum offers first voice oral histories [29]. Additionally, excerpts from the journal of Frank Baker, a Navy sailor on duty aboard the C.S.S. Acadia at the time, can now be read online [30]. Baker’s journal was discovered and published nearly 100 years after the event [31]. Visitors to Halifax may be lucky enough to see the C.S.S. Acadia still floating in the harbour; it is now part of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic [32].

“The first thud shook the ship from stem to stern and the second one seemed to spin us all around, landing some [crew members] under the gun carriage and others flying in all directions all over the deck” [33]

In 2003, the film Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion was released [34].

Many books have been written about the Halifax explosion, such as Survivors: Children of the Halifax Explosion (2000) by Janet F. Kitz [35], Broken Pieces: An Orphan of the Halifax Explosion (2017) by Allison Lawlor [36], and Halifax Explosion: Heroes and Survivors (2011) by Joyce Glasner [37]. These books are available for purchase at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic’s gift shop [38].

For more information about the Halifax Explosion, we recommend a visit to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

References

(see here for full bibliography)

[1] Canadiangis, “Map of the 1917 Halifax Explosion,” accessed September 8, 2023, https://canadiangis.com/geo/halifax-explosion-map.

[2] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Halifax Explosion,” Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion.

[3] Government of Canada, “Halifax Explosion Remembrance Book database, 1917-1918,” Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/a43ed9ca-1f6d-063a-6bc7-66dc422c363e.

[4]Terra Incognita, “Halifax Explosion: Minute by Minute,” Youtube, December 5, 2017, video, 4:59, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JKcXSCzcSZ4.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Halifax Explosion,” Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion.

[8] Canadiangis, “Map of the 1917 Halifax Explosion,” accessed September 8, 2023, https://canadiangis.com/geo/halifax-explosion-map.

[9] Lois Kernaghan, Richard Foot, “Halifax Explosion,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, Government of Canada, May 25, 2022, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/halifax-explosion.

[10] The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Halifax Explosion Map,” NS Board of Insurance Underwriters, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/primarysources/plan-showing-devastated-area-of-halifax-city-ns.

[11] Nsarchives, “Halifax Explosion: The Aftermath and Relief Efforts (1917),” Youtube, August 17, 2010, video, 13:11, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5PImhLMxTXc.

[12] CBC News, “A city destroyed: The Halifax Explosion, 100 years later in 360-degrees,” Youtube, December 1, 2017, video, 5:38, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSuX9RvLq54.

[13] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Vincent Coleman and the Halifax Explosion,” Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Province of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion/vincent-coleman-and-halifax-explosion.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Historica Canada, “Heritage Minutes: Halifax Explosion,” Youtube, March 2, 2016, video, 1:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rw-FbwmzPKo.

[16] Find a Grave, “Mount Olivet Cemetery,” July 22, 2001, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/639383/mount-olivet-cemetery.

[17] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Halifax Explosion,” Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion.

[18] Canadiangis, “Map of the 1917 Halifax Explosion,” accessed September 8, 2023, https://canadiangis.com/geo/halifax-explosion-map.

[19] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Halifax Explosion,” Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion.

[20] Community, “Alan Syliboy Brings ‘Tufts Cove Survivor’ to Halifax Harbour Waterfront,” MacGillivray Injury and Law, July 19, 2022, accessed September 7, 2023, https://macgillivraylaw.com/articles/alan-syliboy-brings-tufts-cove-survivor-to-halifax-harbour-waterfront.

[21] Community, “Alan Syliboy Brings ‘Tufts Cove Survivor’ to Halifax Harbour Waterfront,” MacGillivray Injury and Law, July 19, 2022, accessed September 7, 2023, https://macgillivraylaw.com/articles/alan-syliboy-brings-tufts-cove-survivor-to-halifax-harbour-waterfront.

[22] Ruck, Lindsay, “Clement Ligoure,” Canadian Encyclopedia, March 3, 2023, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/clement-ligoure.

[23] ibid.

[24] ibid.

[25] ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Halifax Explosion,” Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/halifax-explosion.

[28] Dartmouth Heritage Museum, “Exhibits,” Dartmouth Heritage Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.dartmouthheritagemuseum.ns.ca/exhibits/.

[29] Dartmouth Heritage Museum, “Oral Histories: Halifax/Dartmouth Explosion Series,” Dartmouth Heritage Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.dartmouthheritagemuseum.ns.ca/learn/oral-histories/.

[30] Marc Wortman, “A Newly Discovered Diary Tells the Harrowing Story of the Deadly Halifax Explosion,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 14, 2017, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/newly-discovered-diary-tells-harrowing-story-deadly-halifax-explosion-180964066/.

[31] ibid.

[32] “C.S.S. Acadia,” Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/what-see-do/exhibits/css-acadia.

[33] Baker, Frank, quoted in Worman, Marc, “A Newly Discovered Diary Tells the Harrowing Story of the Deadly Halifax Explosion,” Smithsonian, July 14, 2017, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/newly-discovered-diary-tells-harrowing-story-deadly-halifax-explosion-180964066/.

[34]Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion, directed by Bruce Pittman (2003; CBC, Tapestry Pictures).

[35] Janet F. Kitz, Survivors: Children of the Halifax Explosion (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2000).

[36] Allison Lawlor, Broken Pieces: An Orphan of the Halifax Explosion (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2017).

[37] Joyce Glasner, Halifax Explosion: Heroes and Survivors (Formac Publishing Company, 2018).

[38] Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, “Marine Heritage Store,” Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Province of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Museum, accessed September 8, 2023, https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/visit-us/marine-heritage-store.

IMMIGRATION & PIER 21

Halfiax’s Pier 21 is a famous port where approximately one million newcomers arrived in Canada between 1928-1971 [1]. It is known as the “Gateway to Canada” [2]. While most newcomers arrived in Halifax, many did not settle in the city [3]. Instead, they moved on to other areas across Canada, looking for a new life.

Photo of a “Welcome to Canada” sign, written in English and six other languages. Above the sign is a picture of Queen Elizabeth. Photo taken by Madeline Rae at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21: The Pier 21 Story exhibition (2023) [4].

While Pier 21 was a gateway to a new, promising life for many, it was also a site that is implicated in some difficult histories. Some were kept at Pier 21’s detention center [5], waiting for health checks, or for proof of their political affiliations [6], and many others were turned away from the port, including Jewish refugees and other displaced persons during WWII [7].

Image from The Canadian Immigration Story exhibit depicting a displaced person saying goodbye to their family before leaving for Canada. Photo: Madeline Rae (Aug. 2023) [19].

Over the years, immigration restrictions were tightened, and it was difficult for newcomers. Racism and discrimination also played a key role in these difficulties as “British” immigrants were treated better than “foreign” immigrants.

For further information, we recommend visiting Halifax’s Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 [20], located in the southeast end of Halifax on the waterfront. The museum’s website offers a page dedicated to the complex immigration history of Canada at Pier 21 [21][22]. It also offers links for those interested in investigating immigration records [23]. If you plan to visit the museum, we recommend leaving enough time to watch the immersive video Contributions, which celebrates the contributions of newcomers to Canada over the years [24]. Contributions has an accompanying website that offers links to various stories of newcomers [25].

The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 features the permanent exhibition “The Canadian Immigration Story” [8]. Visitors can look at a timeline of Immigration in Canada, beginning with images of traditional Mi’kmaw petroglyphs. After this, the settlement of Acadia in 1604 [9], all the way to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act of 2001 [10]. The exhibit features stories of individual newcomers (BMO Oral Histories Gallery), specific histories of Mi’kma’ki and Treaty Rights, historic immigration posters, and even a Canadian Citizenship test that visitors can take [11]. The stories along the walls in the exhibition are primarily positive, but not all are; nuanced examples are offered of the difficulties and grief that can come with immigration.

Other exhibitions at the museum include Hearts of Freedom - Stories of Southeast Asian Refugees (a project of Hearts of Freedom), and #HopeandHealingCanada (an installation speaking to residential schools by Metis artist Tracey-Mae Chambers).

Why Halifax? & Leaving Halifax:

Halifax was, and continues to be, one of the most popular ports in Canada’s history, largely due to the access the harbour affords, as it is one of the deepest ice-free harbours in the world. However, this is also due to the railway, which served as a direct mode of transit across Canada and down into the United States [26]. The railway into Halifax no longer functions and is not a federally protected Heritage site. Most immigrants who arrived at Pier 21 did not stay in Halifax [27]. Instead, they traveled in “colonist cars” to other parts of the country.

Deportation & Detention Centers:

Pier 21 had “accomodation” rooms as well as “detention” cells [28]. While the detention cells were reserved for potentially “dangerous” and suspicious persons, the accommodation rooms were also cell-like, separated by gender, and had “simple metal beds and adjoining bathrooms, secured against escapes with bars or mesh in the windows” [29].

“And every morning they would open the door and let us out and every night, I think eight o’clock or nine o’clock, they would lock the doors. And our room faced the railroad tracks and my sister and my mother and I would look, I’m not joking, we would be like this. Tears running down our faces, seeing all these people getting on their trains and going and we were still there. And we were here for three months.” (Jackie Eisen, age 11) [30]

The “Wheel of Conscience” at Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. Photo by Madeline Rae (August 2023) [36].

A placard on the side of a replica “Colonist Car” tells the story of the journey from Pier 21 in Halifax across Canada for many newcomers. Photo by Madeline Rae (August 2023).

Not everyone who arrived at Pier 21 was welcomed into Canada. The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 features a sculptural installation titled The Wheel of Conscience [31]. The installation was designed by Polish-born architect Daniel Libeskind [32]. It is a memorial sculpture for the 900 Jewish refugees/displaced persons who were turned away from Pier 21 during WWII [33]. The sculpture moves with four interlocking gears that move each other: “hate” moves “racism,” which moves “xenophobia,” and finally, “anti-Semitism” [34]. When the passengers were turned away, ultimately the ship returned to Germany, and over a ¼ of the people on board were killed in Nazi concentration camps [35].

To learn more, we recommend visiting the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 [37] as well as checking out their series of videos on the history of Pier 21 [38]. Destination Canada is a graphic novel published by the Consulate General of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and it tells the story of ten Dutch immigrants to Canada [39]. A few stories from the book are featured in the museum’s exhibitions, and the book is available in the gift shop. The museum’s website’s Soft Landing page features multiple videos about newcomers to Canada [40], and a page with links to Countless Journeys [41], a podcast on immigration that covers topics from food, to artwork, and stories of journeys and arrivals. Today, Pier 21 and its neighbouring ports remain active as docking spots for cruise ships carrying tourists [42].

References

(see here for full bibliography)

[1] Paul Bishop, “Pier 21,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, April 30, 2015, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/pier-21.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “the Pier 21 Story,” Exhibition, Pier 21, Halifax, visited August 29, 2023.

[4] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “Welcome to Canada,,” in the Pier 21 Story, Exhibition, Pier 21, Halifax, visited August 29, 2023.

[5] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “Exploring Pier 21’s Immigration Quarters,” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/exploring-pier-21-immigration-quarters.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Daniel Libeskind, “Wheel of Conscience,” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, Government of Canada, accessed August 2023, https://pier21.ca/wheel-conscience.

[8] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21,”The Pier 21 Story,” Exhibition, Pier 21, Halifax, visited August 29, 2023.

[9] Nicolas Landry, Pere Anselme Chiasson, Dominique Millette, Clayton Ma, “History of Acadia,” Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, November 23, 2020, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/history-of-acadia.

[10] Government of Canada, “Acts and Regulations - Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada,” Government of Canada, December 21, 2018, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/mandate/acts-regulations.html.

[11] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21,”Canadian Immigration Story,” Exhibition, Pier 21, Halifax, visited August 29, 2023.

[12] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21,”Canadian Immigration Story,” Exhibition, Pier 21, Halifax, visited August 29, 2023.

[13] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “Hearts of Freedom - Stories of Southeast Asian Refugees,” Pier 21, Hearts of Freedom, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/hearts-freedom-stories-southeast-asian-refugees.

[14] Hearts of Freedom, “Hearts of Freedom,” Hearts of Freedom, accessed September 8, 2023, https://heartsoffreedom.org/.

[15] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “#HopeandHealingCanda,” Pier 21, Tracey-Mae Chambers, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/hope-and-healing-canada.

[16] Tracey-Mae Chambers, “Tracey-Mae,” Tracey-Mae Chambers/The Queen Bee, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.traceymae.com/.

[17] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “Historic Pier 21,” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/research/historic-pier-21.

[18]Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/.

[21] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “Immigration History,” Pier 21, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history.

[22]Ibid.

[23] Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, “Immigration Records and Family History,” Pier 21, Government of Canada, accessed September 8, 2023, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-records-and-family-history.

[24]Ibid.

[25] Pier 21, “Contributions,” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, accessed September 8, 2023, https://contributions.pier21.ca/.